Advertisement

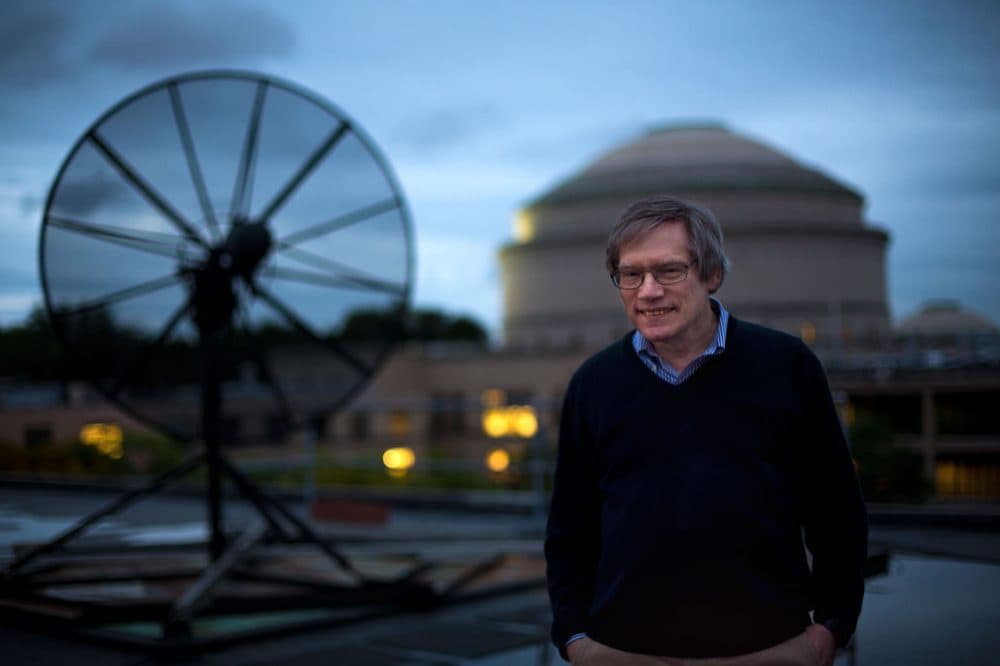

Visionaries: MIT's Alan Guth Made A 'Spectacular Realization' About The Universe

Resume

One night 35 years ago, MIT physicist Alan Guth had an epiphany — not the kind that you and I may have about our daily lives — but a bold theory about how the universe expanded in the milliseconds after the Big Bang.

His huge scientific breakthrough would come to be called "inflation," and these days it's accepted as the most plausible explanation for the evolution of the universe. We profile Guth for our ongoing "Visionaries" series.

Messiest Office, Brilliant Mind

Alan Guth is a man with a tendency to laugh at himself. That's clear from the first question I ask him: How old are you?

"I'm 67 years old," he says. "I don't think I'm really that old, but that's what they say," he says, chuckling.

Guth jokes about his age, but it's true, he shows signs of aging — with a mop of grayish hair, a habit of poor posture and a son who's a math professor at MIT in his own right.

Guth's office is in a state of constant entropy, littered with old science magazines and half a dozen Coke Zero bottles (he opens another one up as we talk).

"I should mention it used to be much, much worse and I, in fact, did once win a contest by The Boston Globe for the messiest office in Boston," he says amid laughs.

But behind his self-deprecating humor is a brilliant scientific mind.

Guth is revered by students and colleagues as a legend, albeit a modest one with humble roots.

He grew up in a tiny town in New Jersey, where his dad ran a couple of small businesses — first a grocery store, then a dry cleaners. His mother sometimes helped out in the shop, but mainly stayed with the kids.

"My parents were not at all involved in science," Guth says. "In fact, neither of them went to college."

When Guth was 16, he became interested in physics, thanks to a high school science teacher.

"He did have a way of making clear that physics isn't about things going up and down incline planes, but physics is about really understanding reality," Guth says.

And so Guth resolved at that ripe age that he would become a physicist. He says it "blew his mind" that he could do calculations based on a small number of principles to essentially explain the world.

And to study physics, he reckoned he ought to go to MIT.

"I had considered MIT a place where brilliant people came," he says.

Guth didn't consider himself that brilliant. He figured he would survive in the classroom but shine on the sports field.

"In high school, I was the best broad jumper on our team, and I kind of thought that when I got to MIT, I'd probably still be the best broad jumper, cause why do broad jumpers come to MIT?" he says. "But it turned out to actually be the other way around. There was another person in my class who could jump about 3 feet further than I could."

He had a similarly sad fate with the Debate Team and the Chess Club. Guth was no good at extracurriculars.

"But I still got to be at the top of my physics class," he recalls.

In fact, Guth had such a knack for physics he stuck around MIT for his master's and his Ph.D.

'SPECTACULAR REALIZATION'

But academia can be unfriendly, even to brainy scientists. Guth bounced around from post-doc to post-doc — Princeton, Columbia, Cornell and Stanford.

During this time, Guth was trying to understand a fundamental problem in physics: how the early universe expanded so quickly, from a nugget that was a billion times smaller than a single proton.

"If you consider the universe one second after the Big Bang, the expansion rate would have to have been just right to an accuracy of 15 decimal places, or else the universe would really not work," Guth explains.

What he means is that if the universe expanded too quickly, it would have flown apart before galaxies could form.

"And if the universe were expanding slower than we thought it was, the universe would have recollapsed before galaxies could form," he adds.

For Guth, this seemed like an inexplicable mystery of physics.

But then one day in December 1979 at his rental home in Menlo Park, California, he had a eureka moment.

"I went home one night and wrote down the equations that described how the universe expanded," he says matter-of-factly.

At the top — in all caps — he wrote: "SPECTACULAR REALIZATION."

“I went home one night and wrote down the equations that described how the universe expanded.”

MIT physicist Alan Guth

Those notes are now housed at the Adler Planetarium in Chicago.

They explain how the universe ripped apart really quickly in the immediate aftermath of the Big Bang, and they form the crux of Guth's theory, called "cosmic inflation," which is premised on the belief that a speck within the early universe was filled with a repulsive gravity force that drove the universe apart.

And, because of that theory, suddenly the man who had been roaming the country for work was an instant science celebrity, and colleges were courting him. He went on a cross-country tour explaining his new idea.

"The very last night of this trip around the country, I was at the University of Maryland, and they took me out for a Chinese dinner, which is something physicists do a lot, and my fortune said, 'An exciting opportunity awaits you if you're not too timid,' " Guth recalls.

Guth decided, "Yeah, probably the fortune cookie was right, what do I have to lose?"

He picked up the phone and called MIT — the place where he dreamed of working.

"[I] didn't know exactly how to phrase it, but I said, 'You know, you didn't have a job, so I didn't apply for a job, but if you had a job, I would be interested in it,' " he recalls. "And, very surprisingly, the next day they called me back and made me an offer. For a job that didn't exist."

This was 1980, and Guth has been teaching at MIT ever since.

One of his former students, David Kaiser, now a professor at MIT, says Guth isn't just smart, he's authentic.

"In his own first article that introduced much of the world to this notion of cosmic inflation, he pointed out the fatal flaw for his own idea," Kaiser says. "I mean, that's extraordinary to me. I take it as a sign, not just his carefulness, but his really kind of relentless scientific honesty and straightforwardness."

Seeking More Evidence For 'Inflation'

On Monday nights, Guth meets with students over science calculations and pizza to dig into new research.

One of his students, Katelin Schutz, who has since graduated and is now pursuing a Ph.D. at Berkeley in California, explains that a friend from her hometown wants Guth's autograph.

"In the physics world, he's always been a rock star," Schutz says. "Everyone was sort of waiting for, when will he win the Nobel Prize? Not if."

Guth's inflation theory is not fact but, for years, it has been accepted in the scientific community as the standard explanation for the expansion of the universe.

On March 17, 2014, it looked like Guth finally had concrete confirmation.

The news made The New York Times, BBC News, the TV nightly news. It was theoretically the biggest scientific breakthrough in years.

A group of scientists at Harvard had allegedly found the "smoking gun" for Guth's inflation theory — gravitational waves in the early universe. These ripples presumably would have been created by inflation.

But, just last month, scientists admitted those little waves they saw were just dust — literally, cosmic dust. In other words, their groundbreaking discovery was an error.

The results were a letdown for Guth, but he's still "confident" cosmic inflation took place.

"There's quite a bit of other evidence for inflation already, and I find that evidence quite convincing," he said.

And, it's true, the evidence for inflation is convincing for a lot of folks in the physics world, but there are still skeptics.

And, for Guth, the man who thought he had seen his own idea definitively proven in his own lifetime, he'll have to wait a little longer, til the dust settles — and more experiments offer more conclusive answers.

This segment aired on February 26, 2015.