Advertisement

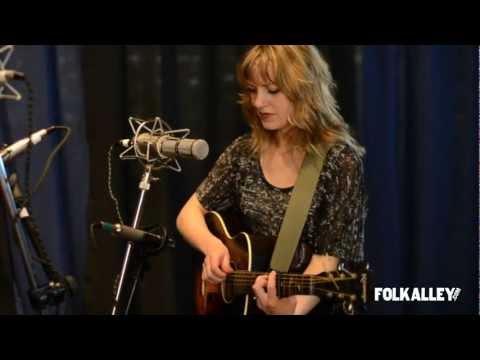

Once More, With Feeling: Mitchell And Hamer’s ‘Child Ballads’

“Child Ballads,” the simply-titled album from Anaïs Mitchell and Jefferson Hamer, is a mere seven tracks long, but there are plenty of other things to count: six riddles, three wicked mothers, two drowning incidents, five marriages, three supernatural occurrences, two babies conceived out of wedlock, four kings, three different men named Willie, lots of steeds, one suicide, and one hanging.

None of this is unusual given the material, which was gathered from Francis James Child’s iconic folksong collection “The English and Scottish Popular Ballads,” first published in 1882 while Child was a professor at Harvard University. And since we’re counting, Mitchell and Hamer are not the first to have embarked on such a project. Bob Dylan, Nic Jones, Richard Thompson, and Joan Baez all famously borrowed from the collection, and “Child Ballads,” is awash in their echoes, a quietly prepossessing addition to the ranks of traditional balladry made modern.

Yet despite the wealth of existing recorded material, the creation of “Child Ballads,” which Mitchell and Hamer will perform at Club Passim in Cambridge on April 10, was a laborious process. It began after Mitchell, a Vermont native living in Brooklyn, hired the Brooklyn-based Hamer as her accompanist and the two discovered a shared love of ‘70s folk revivalists like Martin Carthy and Paul Brady.

“We would go on long car rides together—you know, we were on tour—and someone would have the books in their lap, and they would be leafing through different verses,” remembers Hamer.

Of the 305 songs collected in Child’s book, some have upwards of 15 annotated versions, and none include sheet music. Needless to say, parsing it was a daunting task, and at first the duo relied on other singers’ renditions for guidance.

“As the project progressed we got a lot bolder with writing our own melodies, and piecing together stories more or less from scratch using the Child books as the source,” says Hamer. “But in some cases we did make up our own words when we couldn’t find what we were looking for. We called that ‘bushwhacking.’”

In both Mitchell’s and Hamer’s telling, the Child ballads’ appeal is ancient and somewhat mysterious. “They contain these mystical pagan elements, shape-shifting and witches, strange natural phenomenon,” muses Hamer. “I think newer songs, especially coming out of a Christian tradition ... you don’t get some of those elements that seemed to us to be really exotic.”

If any one theme unites the songs on “Child Ballads,” it is transgression. Women get pregnant before marriage; sons defy their mothers; the poor struggle—without much success—against the rich. These stories are more Grimm’s Fairy Tale than Disney cartoon. Mitchell and Hamer understand this, and they wisely retain the songs’ gristlier bits, happy endings or no.

The result is a testament to their interpretive talents. The seven songs on “Child Ballads” will be familiar to any folk music buff—“We did not set about trying to unearth hidden gems,” explains Hamer—but a closer listen reveals how a few subtle tweaks can change a story.

For Mitchell and Hamer, the biggest stumbling block was the archaic-sounding language. “The stories are so fantastic, and we wanted them to be comprehended,” says Mitchell. “And we wanted people to understand them who might not necessarily be familiar with this kind of music or with some of the old language that appears in these songs.”

In some cases, that meant jettisoning whole segments of a story, as was the case with “Tam Lin,” a popular ballad about a lady whose shape-shifting boyfriend (the aforementioned Tam Lin) turns out to be a prisoner of the Fairy Queen. “Commonly, the fairies are the explanation for why Tam Lin is this supernatural character in the woods that transforms into all these wild animals,” says Hamer. “We just decided that that image, which is a beautiful image, could serve as a metaphor for standing by someone you love when things don’t go so well.”

In the end, simplicity dictated the album’s sound, too. After two recording attempts the duo abandoned their original vision, a folk-rock album in line with Mitchell’s two previous releases, the epic “Hadestown” and the dynamic “Young Man in America.” With Nashville producer Gary Pazcosa, known for his work with Dolly Parton and Alison Krauss, they settled on a restrained, almost subdued aesthetic.

“The way we always sang these songs was in the car, or in someone’s living room: two guitars and two voices,” explains Mitchell. Hamer points to harmony singing as the source of their musical bond, and on “Child Ballads” you rarely hear one singer without the other. It helps that both have such memorable voices: Hamer with a fragile, Neil Young-esque quality and Mitchell with her arresting girlishness. Together, they weave a gossamer spell that lingers long after the final chord, like a story remembered from childhood beginning “Once upon a time.”

Anaïs Mitchell and Jefferson Hamer will perform at Club Passim in Cambridge on April 10.

Amelia Mason is a writer and musician living in Cambridge. Those pesky "day jobs" she has to "make money" really aren't worth mentioning. Naturally, she also has a blog: blog.ameliamason.com

This article was originally published on March 28, 2013.

This program aired on March 28, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.