Advertisement

'All roads lead to Berlin!': Soviet Artists Fight The Nazis In WWII

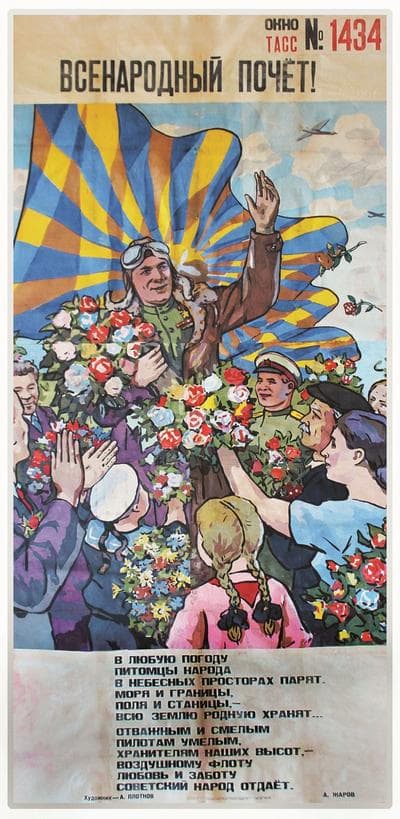

Before dawn on June 22, 1941, some 3 million German troops, 3,600 tanks and 2,700 planes swarmed into the Soviet Union. Over the next couple days, as Soviet troops were overwhelmed by the Nazi advance, Soviet artists Mikhail Chermnykh, Pavel Sokolov-Skalia and Vladimir Denisovskii met with leaders of their government to launch production of posters aimed at reassuring the public, inspiring their military response, and to rally support abroad.

“These posters were used as propaganda,” says Jim Lapides, owner of International Poster Gallery (205 Newbury St., Boston), where 45 of the now rare posters are on view in the week-long exhibit “War and Peace: TASS Agency Posters from the Soviet Union 1941-1964” through May 7. “They were sent to the United States. They were sent to the Brits. They were not just internal. They wanted them to be like history painting. They wanted to express the idea that the Soviet Union is powerful and has history and will have more history.”

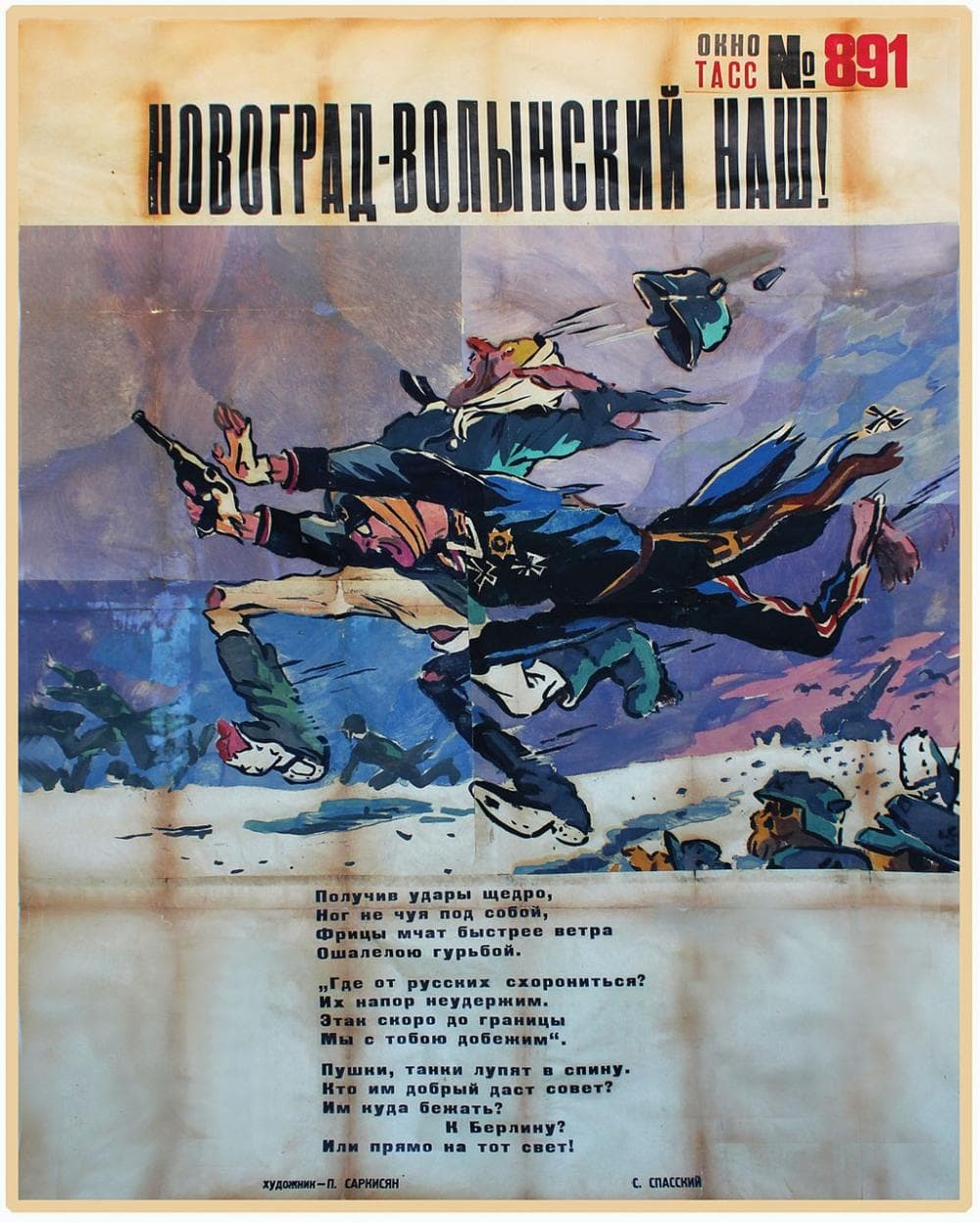

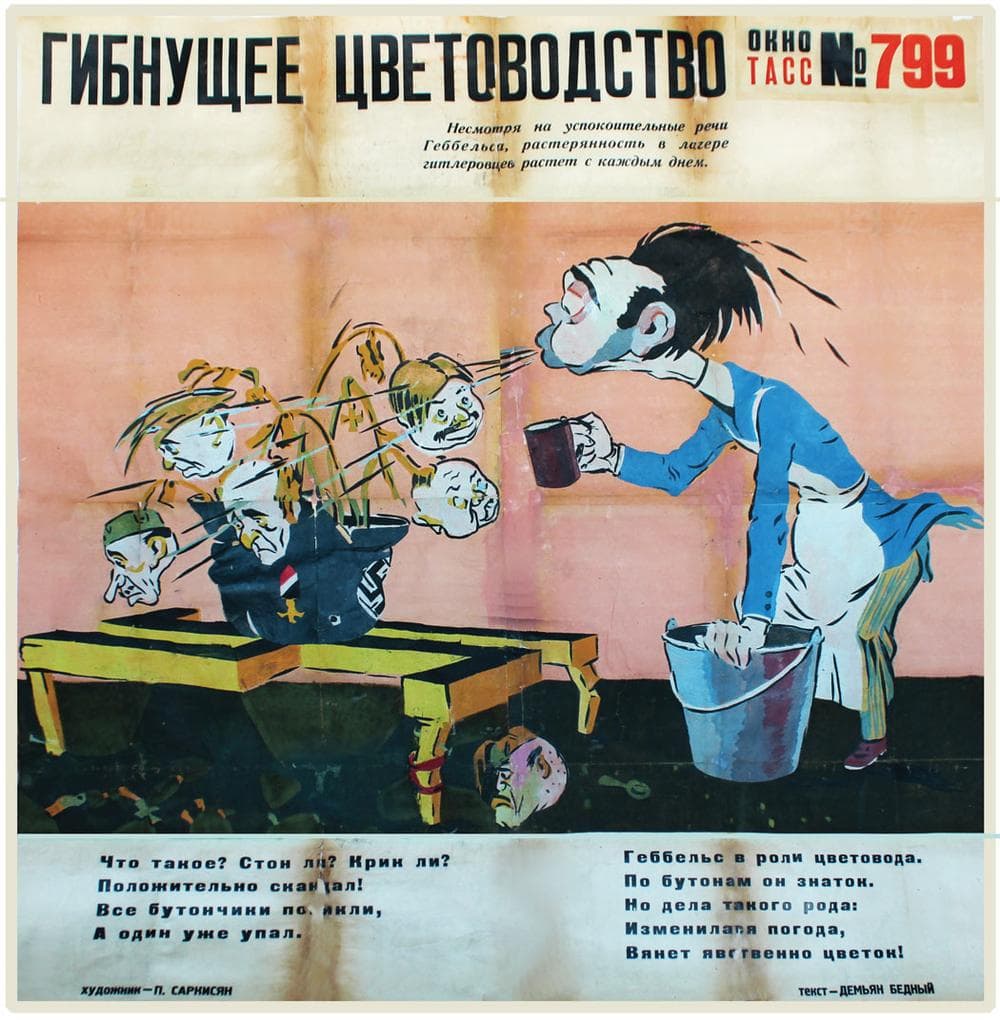

Over the next five and a half years, as the Soviet Union struggled back to its feet and ultimately pushed the Germans all the way back to Berlin, the government-sponsored TASS News Agency program produced some 1,485 hand-stenciled posters for Soviet shop windows.

The posters, often running 3 feet wide by 6 feet tall, and at times featuring more than 50 colors per print, tell a Soviet story of the war—of defiance, of liberating their land, of revenge, of Stalinist values, of national pride. They caricature Hitler as a wrinkled rat-nosed twerp running scared; getting punched in the jaw by Soviet “forces [who] have made it all the way to the border of the USSR”; and seeing his fate as constellation of starts arrayed like a noose.

“Nobody did satire like the Soviets,” Lapides says. “They could really rip you. Some of these things are just dripping with sarcasm and bitterness. They’re powerhouses.”

Other graphics valorize charging Soviet infantrymen; promote care of machines and production of wheat and rye; and pledge that Hitler “will reap his death.” They urge the Red Army cavalry to “annihilate the German-fascist abominations”; celebrate the Allied liberation of Paris and then Rome (“All roads lead to Berlin!”); and honor the Soviet navy, artillery and tankers. Later posters champion “Enlightened Stalinist law,” Stalin’s new five-year plan, and the anniversary of the 1917 Russian Revolution—of course, with no mention of labor camps and other vast cruelties of Soviet ruler Joseph Stalin’s murderous dictatorship.

In early 1945, with Soviet forces closing in on Germany from the east and Allied forces coming from the west, Solov'ev, M. designed the poster “Salute!,” which depicts a crowd cheering as it watches fireworks lighting up the sky over Moscow’s Red Square in honor of the sacrifices of their countrymen. Berlin fell to the Soviets and then Germany unconditionally surrendered in early May.

TASS posters were exhibited in the United States during the war—including in the 1943 show “The Soviet Artist in War” at New York’s Museum of Modern Art—but the alliance between the United States and the Soviet Union, forged around their common enemies in the war, fell apart afterward, and the two nations became enemies in the ensuing five-decade long Cold War.

“Most Soviet posters were very rare in the United States until Perestroika,” the loosening of Soviet restrictions in the late 1980s, Lapides says. “When Perestroika happened there was a huge amount of material that became available for the first time.”

The past decade has seen a surge in interest in Soviet World War II graphics, as evidenced by the 2011 exhibit “Windows on the War: Soviet TASS Posters at Home and Abroad, 1941-1945” at the Art Institute of Chicago in 2011 and “Views and Re-Views: Soviet Political Posters and Cartoons” at Brown University’s Bell Gallery in 2008.

Now though, Lapides says, “the market supply has dried up. Quite frankly, it’s hard to find quality pieces. …. Most of them are winding up in the hands of Soviet collectors.”

This article was originally published on May 03, 2013.

This program aired on May 3, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.