Advertisement

Immortalizing The First African-American Civil War Regiment

On July 18, 1863 — 150 years ago today — the Union's first African-American regiment of the Civil War fell to Confederate troops in the battle at Fort Wagner, S.C.

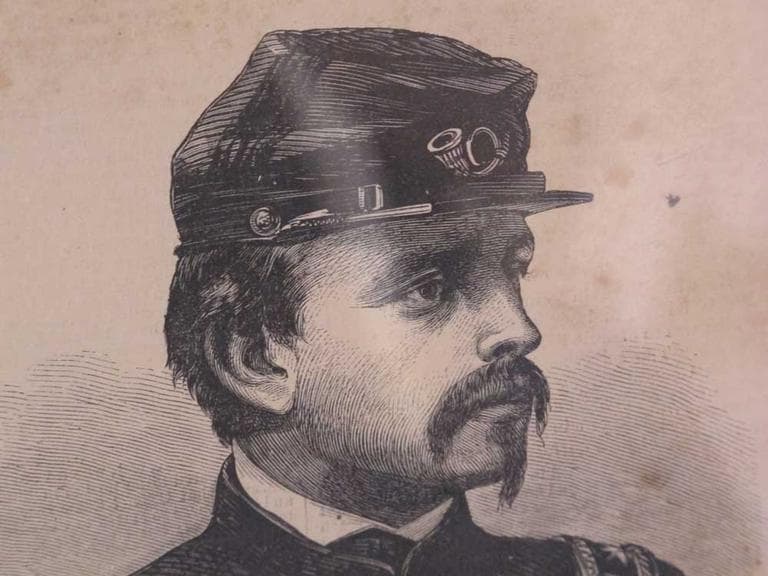

The newly freed soldiers of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment were led by Col. Robert Gould Shaw and their bravery is immortalized in a memorial directly across from the State House on the Boston Common. It’s been called “a symphony in bronze.”

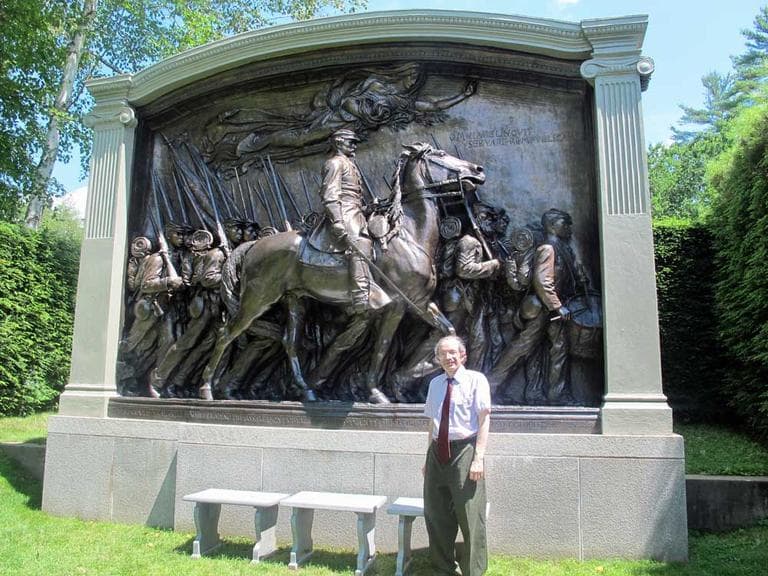

But great American sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens cast other versions of the iconic relief. I took a road trip to see the artist’s final expression of the 54th at his home in Cornish, N.H.

The dramatic story behind the memorial and the 54th Regiment plays out to full effect in the 1989 film “Glory,” starring Matthew Broderick as Shaw.

Early in the movie, Massachusetts Gov. John Andrew, abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass and Shaw’s father Francis George introduce what would be a watershed idea: a regiment of black soldiers. Douglass, played by actor Raymond St. Jacques* , says, “We will offer pride and dignity to those who have known only degradation.” Gov. Andrew tells Shaw that his name has been submitted to be colonel of what would be known as the 54th Massachusetts Regiment.

Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site curator Henry Duffy appreciates Hollywood’s take on this period of history, but told me he sees the 54th Regiment burst to life in bronze every time he contemplates the memorial on the park’s lush grounds.

"It’s like a movie cell," Duffy explained. "In the front [of the relief] the procession is led by a drummer, but half the drum is off the edge of the picture. And in the back, the last soldier, the legs are cut off. So you get a sense that there’s more happening in front and in behind."

The feeling of motion is palpable. It’s like a giant diorama, with 40 or so black soldiers in rows marching to war — some handsome, some gnarled, all worn but walking proudly. They flank Shaw, who sits high on his horse.

“There are things here on this monument that only the pigeons see,” Duffy told me. “The embroidered detail on the top of the colonel’s cap,” for one.

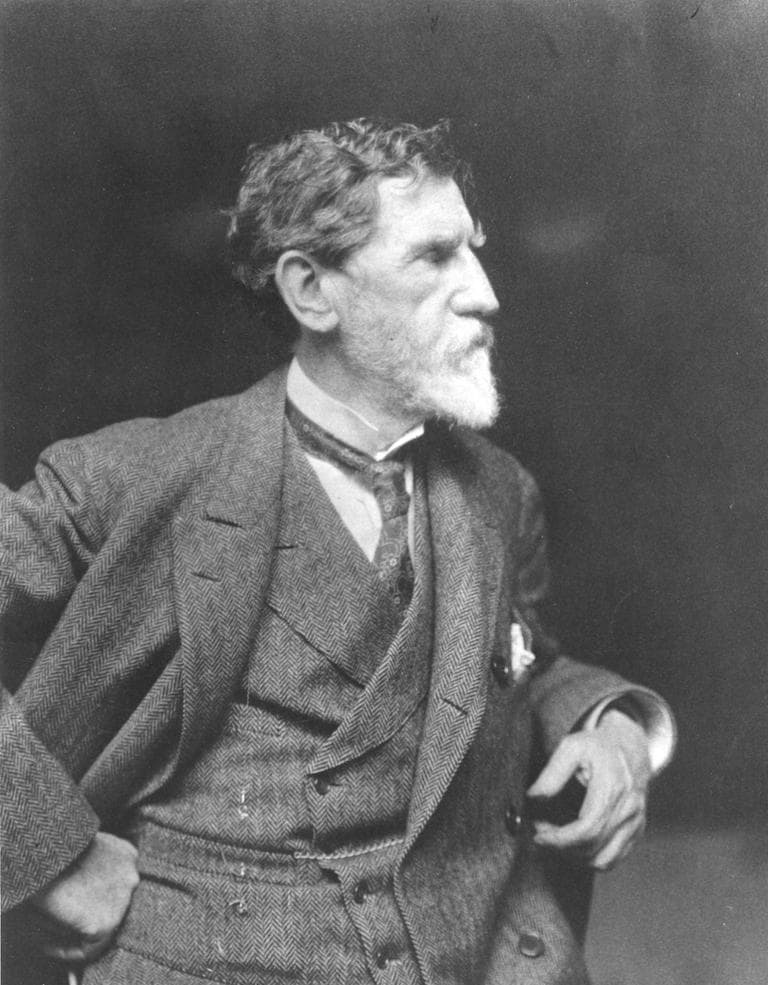

The meticulous sculptor trained in Paris was already world famous when a committee in Boston commissioned him to make a monument for Boston Common in 1883.

“He was originally focusing just on Col. Shaw,” Duffy explained. “It was Shaw’s parents who told him, ‘No, if you’re going to do a monument to our son, you have to include his men because he was dedicated to his men and the men have to be part of it.' "

Wanted: Volunteers Of African Descent

Recruiting black soldiers was strategic as well as symbolic during the Civil War. The carnage was far worse than anyone expected and the Union needed more men. President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, issued in January 1863, enabled newly freed slaves to join the effort. Shaw, the son of a wealthy, Boston abolitionist, chose to fight with the 54th at Fort Wagner rather than command from the sidelines. Six hundred men stormed the parapet 150 years ago today; an estimated 272 were killed, wounded or captured. Shaw, just 25 years old, was the first to go, making him a hero to his surviving men and the rest of the Union.

"This man took a bullet for a black man in 1863," the curator said. "That didn’t happen very often, so it was something that really inspired them."

Shaw’s sacrifice inspired Augustus Saint-Gaudens to the point of obsession. The sculptor was supposed to complete his the memorial commission for Boston Common in six months — instead he took 14 years.

“I always think that it haunted him,” Duffy mused. “I think he just couldn’t get it out of his mind.”

The artist knew this work would be his most important. Even after installing the first piece on Boston Common, he continued to tinker for four more years to make the final version that sits on the grounds of his home. Duffy calls the artist’s connection profound.

"I think, like Shaw himself, Saint-Gaudens had his eyes opened. He had never had much to do with black people — just like Shaw — so that when he had to do this he was faced with having to, for the first time in his life I think, look at people and not stereotypes,” Duffy explained.

Saint-Gaudens sat with black models in his studio for hours, where he got to know about their lives. Their realistic faces have moved countless others from the moment the Shaw memorial was dedicated in Boston, including writer Henry James, poet Robert Lowell and composer Charles Ives.

"The Shaw memorial is the first time when black Americans were ever portrayed in a work of sculpture as heroic," said Boston historian David McCullough. "Otherwise, they were either background servants or there for someone’s entertainment as musicians or dancers. But here they are the heroes who would, many of them, pay the ultimate price.”

McCullough urges every American to see the Shaw memorial up close and calls it his favorite monument in Boston. The writer’s latest book, “The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris,” includes a chapter on Saint-Gaudens and the author traveled to Cornish to see the artist’s final rendition for himself. The historic site gets about 30,000 visitors a year.

Bob Magner, 73, traveled to Saint-Gaudens' home in New Hampshire from Washington, D.C., but he grew up in Somerville. He said he’ll never forget seeing the Shaw memorial on the Boston Common as a kid.

"It was interesting because you know it obviously shows black soldiers with a white officer, and I grew up in a white ghetto basically and I wasn’t very familiar with black people," Magner recalled. "It was something that showed me that black people had a prominent role in the Civil War.”

"When an individual encounters this monument and sees this officer on a horse and the black men surrounding him, and it sits across the Massachusetts State House, you have got to ask yourself, ‘Why?' ” said Beverly Morgan Welch, who directs the Museum of African-American History in Boston. "And that ‘why’ begins to tell you that black people in America have been here since the beginning and have contributed to all manner of the development of this country.

"Abraham Lincoln said, if any one place in the nation is responsible for the emancipation of the enslaved and the Civil War, it is Boston,” she added.

Morgan Welch said the Shaw memorial embodies and rebroadcasts that history. It’s also a reminder of how integrated the abolitionist movement was in Massachusetts. That’s one of the many reasons why the black heritage trail walking tour in Boston starts at Saint-Gaudens' masterwork.

The Museum of African American History is remembering the 54th Regiment in the current exhibition, “Freedom Rising,” that focuses on the abolitionist movement in Massachusetts.

The Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site in Cornish, N.H., opens its show, “Consecration & Monument: Col. Robert Gould Shaw & the 54th Regiment,” on Thursday, July 18 with a curator’s talk. The exhibition runs through Sept. 9, 2013.

Correction: The audio of this story and an earlier Web version incorrectly stated that the role of Frederick Douglass in the 1989 film "Glory" was played by Morgan Freeman. The role was played by Raymond St. Jacques.

Correction: The audio of this story and an earlier Web version incorrectly stated that 272 were killed; in fact, an estimated 272 were killed, wounded or captured.

This program aired on July 18, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.