Advertisement

Walking In Olmsted’s Footsteps: Tours Of Emerald Necklace Parks

"The root of all my good work is an early respect for, regard and enjoyment of scenery… and extraordinary opportunities for cultivating susceptibility to the power of scenery,” Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903) wrote in the 1890s.

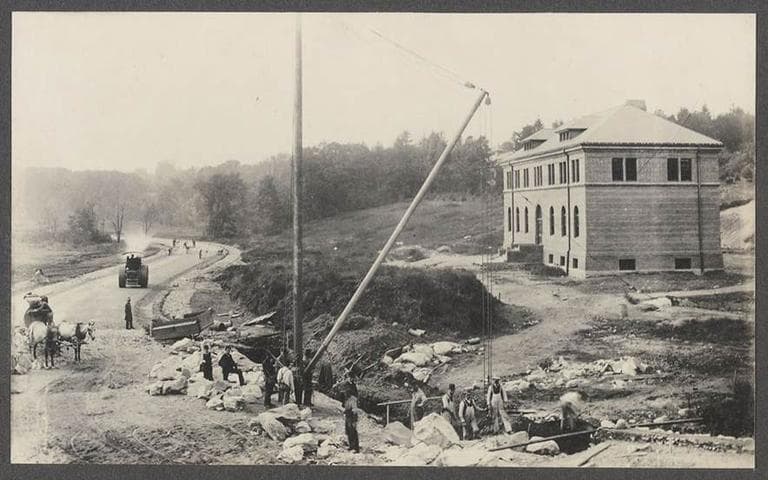

The great landscape architect moved his office from New York, where he designed the landmark Central Park, to Brookline in 1883 as he was working on the park system we now call Boston’s Emerald Necklace. It connected the existing colonial-period Boston Common and 1837 Public Garden with his new Jamaica Pond, Arnold Arboretum and Franklin Park.

The National Park Service’s Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site, based out of Olmsted’s former office, is leading free, public tours of four sites affiliated with Olmsted or his firm over the next month, beginning with Jamaica Pond at 10 a.m. Sunday, Sept. 29, then Franklin Park on Oct. 6, Arnold Arboretum on Oct. 20, and the Blue Hills on Oct. 27.

Franklin Park “is kind of the classic Olmsted Park,” along with Central Park and Prospect Park in New York, says Alan Banks, supervisory park ranger with the Olmsted Historic Site. “It is the classic complete escape from the town, as Olmsted would put it.”

The Boston park’s mix of open meadows (“to give you a sense of freedom”), woods, and pond are an example of the “country park” that grew out of English gardens and the rural cemetery movement (local examples include Forest Hills Cemetery in Boston and Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge). Olmsted aimed to promote shared, democratic access to parkland, while also seeking to foster public health via exercise and access sunlight, things that were growing restricted in increasingly crowded cities and factories of the Industrial Revolution. (Another Olmsted project along the Emerald Necklace was cleaning up the fetid, polluted Back Bay Fens.)

“Olmsted, when he was designing landscapes, he was designing them for a real social purpose,” Banks says.

"Service must precede art," Olmsted himself once wrote, "since all turf, trees, flowers, fences, walks, water, paint, plaster, posts and pillars in or under which there is not a purpose of direct utility or service are inartistic if not barbarous. … So long as considerations of utility are neglected or overridden by considerations of ornament, there will be not true art."

At Jamaica Pond, Banks says, Olmsted showed a light touch. His efforts focused primarily on showcasing the existing glacial kettle hole pond. “A lot of it was removing trees to open up views. In a lot of ways, Olmsted opened up the park that lied beneath a lot of those things,” he says.

Arnold Arboretum, Harvard’s living library of trees, isn’t a classic Olmsted design because its rigorous cataloging in neat rows counters his signature compositions of series of contrasting, natural-seeming, but idealized landscapes. “He did the best that he could working within restrictions,” Banks says.

The Blue Hills Reservation was not designed by Olmsted, but protected by Charles Eliot, a partner in Olmsted’s firm and son of then Harvard University president Charles W. Eliot. It shows how Olmsted’s sense of land relates to the conservation movement signaled by the naming of Yellowstone as the first national park in 1872, the year Arnold Arboretum was established.

Along with securing the Blue Hills, the younger Eliot was also involved in preserving Revere Beach, the first public beach in the country in 1896, and the Middlesex Fells Reservation. And he was one of the founders of the land conservation group, The Trustees of Reservations.

Eliot saw that “large natural areas were slowly, but surely getting destroyed. This was their one chance to collect these New England landscapes,” Banks says.

The parks we have today are examples of his vision—and his success.

This article was originally published on September 27, 2013.

This program aired on September 27, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.