Advertisement

The Updike Touch: Making The Mundane Magical

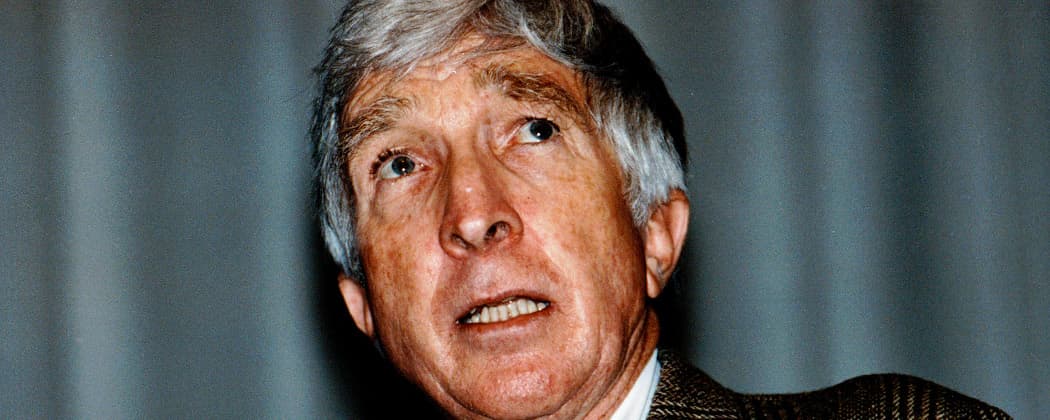

It’s hard to believe the literary reputation of John Updike is still up for debate. At least it feels like it is. As the novelist was approaching senescence around the turn of the century, critics like James Wood and the late novelist David Foster Wallace led a chorus of naysayers who claimed Updike was all style and, priapic matters excepted, no substance. The criticism dogged the great man to his grave in January 2009.

When I hear talk like this I want to drop my Everyman’s Library edition of the Rabbit Angstrom tetralogy, all 2.8 pounds of it, on them. Perhaps even drop it on the part that allegedly does the thinking.

John Updike was a great novelist. There were plenty of misfires, of course, but let he without a “Brazil” or “Toward the End of Time” to his credit cast the first stone. Especially, when the oeuvre extends to 60 books and more than a hundred short stories. Throughout his decades as one of our premier novelists and, many would agree, greatest stylist, Updike succeeded in doing as he’d set out: “to give the mundane its beautiful due.”

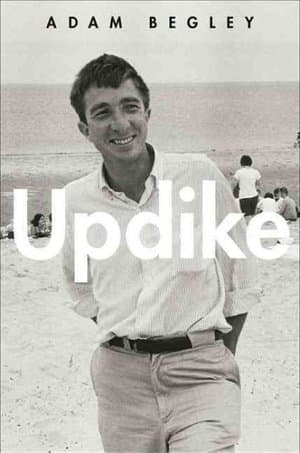

Adam Begley, books editor for the New York Observer and author of the excellent new biography of the man, seems to agree, or at least his book jacket does, calling Updike “a national treasure whose writing continues to resonate like no one else’s.”

Updike actually met Begley when his future biographer was in short pants. The novelist had stopped by the house to pay a visit to Adam’s father, Louis Begley, a fine writer in his own right, and seeing the precocious babe, Updike grabbed some fruit and juggled for the boy bringing a smile to his face.

With “Updike,” the now-grown Begley would seem to return the favor.

Updike was raised in Pennsylvania by a domineering mother who was herself a struggling writer. He respected his father, a teacher, but listened intently as his madré repeatedly told him he was destined to fly. When mom moved the clan from the relatively happening borough of Shillington to a farm in Plowville, Updike was devastated. Shillington was an Edenic little community and a short ride to the big city of Reading. Plowville was about as exciting as its name would indicate. The move and its ramifications would figure in many future stories.

After high school graduation in 1950, Updike hit Harvard, where he joined the famous Lampoon and saw his plan to become an illustrator slowly give way to his burgeoning interest in writing. After graduation, he spent a year in Oxford at the Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art, but even then knew how he’d spend his life.

The New Yorker accepted Updike’s light verse and short stories early on and soon hired him on staff. After about two years of writing “Talk of the Town” pieces full time, Updike knew life in the Big Apple and this kind of work only kept him from his real calling of becoming a novelist. He moved north of Boston with his first wife, Mary, started a family and began his life’s work in earnest. After a couple of well-received novels that made little splash, in 1960, he published “Rabbit, Run,” which jumpstarted a career that would bring him two Pulitzer Prizes, several National Book Awards and every type of mantel bling short of a Nobel.

Begley chronicles all this, as well as the breakup of that first marriage and the infidelities that led to it, Updike’s second marriage to Martha Ruggles Bernhard, and his life as a paterfamilias and man about town. He tells of the author’s amazing productivity: writing fiction, reviewing books, playing Mr. Fixit around the house, having affairs, volunteering in town, traveling and giving talks and picking up awards. For decades, Updike had the energy of ten men, it seems.

Using myriad sources as well as information gleaned from the scores of interviews he conducted, Begley investigates other aspects of Updike’s life, including the crosscurrents of his politics, his reaction to being labeled a misogynist, his spiritual crises and faith, and how the famous man was as a golf partner and dinner host.

The major books and stories are well covered in “Updike.” Begley gives clear-eyed assessments of the work and the bits of real life that went into them. He rates “Rabbit Redux” Updike’s most powerful book, something many would quibble with, but otherwise singles out the hits and misses in a manner that’s both fair and informed.

A recurring theme throughout “Updike” is the author’s penchant for turning reality into fiction. For Updike was not unlike Montaigne, who prefaces his famous essays with the declaration: “Thus, reader, myself am the matter of my book.” There is a danger for any biographer to take this at face value, and Begley walks that line carefully. He tells us the autobiographical aspect of Updike’s novels adds authenticity and resonance to the work, and treads lightly when exculpating from the fiction what he assumes to have been the reality. Very occasionally, Begley oversteps, as when he reads into a ménage à quatre from “The Witches of Eastwick” Updike’s having in mind his first and current wife along with a former mistress.

Memoir has its place, but fiction can often uncover deeper, more universal, truths. “You have to give it magic,” Updike says at one point, and that’s where he excelled. John Updike chronicled life in the second half of the 20th century like few others have and did it beautifully and diligently. As the new biography shows, Updike followed closely that advice of Plato: “Do thine own work, and know thyself.”

Related: An interview with biographer John Begley.

John Winters books and other writings can be found at johnjwinters.com.