Advertisement

There Goes My Hero: The Rise Of The Self-Effacing Everyman In Pop Culture

In one of the final scenes of his rock documentary, "Mistaken For Strangers," director Tom Berninger sits alone inside his room in his brother’s house and sobs. Behind him sits an empty beer bottle and a coffee cup — discernible peaks on a mountainous mess of papers, editing equipment and trash. The moment comes after months of filming and working as a crewmember on tour for indie rock band The National, of which his brother Matt Berninger is the frontman and subject of the film.

“I just want to make something good,” Tom pleads through the camera, unable to make firm eye contact with it. “For [Matt]. For the band … as well as myself.”

The moment is raw, honest and heartbreaking. By this point in the lean 75-minute documentary, we already know Tom intimately. He’s a portly metalhead who can’t seem to get his life together, much less break through the enormous shadow cast by his brother’s limelight. From very early in the film, it’s clear the documentary isn’t so much about an internationally acclaimed rock band as much as it is the portrayal of a man wrestling to overcome himself.

The film is a perfect example of the rise of a very specific kind of antihero that has gained popularity in television, cinema and pop culture recently — the diffident antihero.

Contrary to the traditional definition of an antihero, the diffident antihero is not evil, nor does he alter his moral integrity for the sake of a subjectively higher one, a la Walter White or Dexter Morgan. Rather, he is the self-effacing everyman, defined by his sadness, honesty and grief from having to sacrifice — successfully or not — part of himself in pursuit of a higher form.

Take, for instance, Marc Maron, whose popularity has soared over the last four years because of his "WTF" podcast, which features refreshingly honest conversations with his contemporaries, almost always prefaced by a deeply intimate monologue about his anxiety, neuroses and crippling self-doubt. It’s this level of emotional transparency, along with his impeccable interviewing skills, that has earned Maron a loyal following since the podcast’s debut in 2009. He is upfront about his sadness, unafraid to admit how dissatisfied he is with his own life, and the role he might have played in it.

Like Maron, Lena Dunham — the 27-year-old filmmaker behind "Tiny Furniture" and HBO's "Girls" — also trades in themes of anxiety and failure, which allows her to identify with a generation plagued by statistically alarming rates of depression. More than that, however, Dunham has joined a short, but dominating list of creatives whose characters are defined by the overwhelming contempt they show for themselves.

What's so appealing about self-contempt, you may ask? Or about sadness or anxiety? Well, it's more what those emotions evoke: honesty. Baring one's soul and confronting's ones own inadequacies and insecurities — those are honest experiences, and that kind of honesty breeds authenticity. Such is the defining characteristic of the diffident antihero.

Similar characteristics exist in Louis C.K.’s character in the FX show, "Louie." In a fantastic three-episode story arc at the end of Season 3, C.K. is tapped to become the successor to "The Late Show with David Letterman." To anyone in show business, the offer would have been met with enthusiasm. But for C.K., the pure existence of a challenge means he would have to rise to it — an unwelcome development in his relatively prosaic life. And while there were some external obstacles he had to overcome, the narrative focused mainly on the war that waged within. Do I have what it takes? Is this what I really want? Is my fear holding me back? In the end, the catharsis for C.K. was standing outside of Letterman's office, his arms extended fully skyward, shouting, “I did it!” despite being passed over for the job. It’s in this scene we see the point of the story was not simply about getting the Late Show slot – it was about coming to terms with and overcoming a lesser version of himself in pursuit of his higher form.

It comes as no surprise that podcasts like "WTF," television shows like "Louie" or "Girls," or documentaries like "Mistaken For Strangers" have earned a growing audience. They seem to be tapping into a zeitgeist that is predicated on a fundamental need for honesty and authenticity, perhaps as a result of a growing dissatisfaction and distrust with entities larger than ourselves. According to a 2014 AP poll, an increasing number of Americans say they have little confidence in the government, and other studies suggest that distrust of the media, church and financial institutions is on the rise as well. It's in this rejection of a traditional authority that we are perhaps shifting away from the notion that we need someone to look up to, but that we instead need someone to whom we can look across. In other words, admiration is taking a back seat to relatability.

This idea has only accelerated with the advent of social media, which for some in show business has allowed an unprecedented and unmediated level of intimacy.

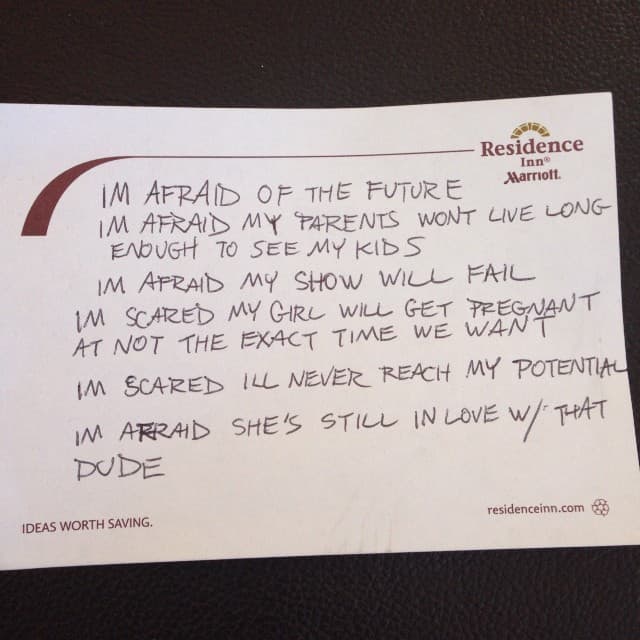

When actor, comedian and rapper Donald Glover confessed feelings of insecurity, fear and sadness on Instagram last year, he offered meaningful insight into the life of a young adult in crisis. “I feel like I’m letting everyone down,” one of his Instagram notes read. “I’m scared I’ll never reach my potential. I’m afraid [my girlfriend] is still in love with that dude,” read another. It was a sincere and refreshing change of pace amid a celebrity culture saturated with carefully manufactured public image.

Rather than destroy his public persona, the Instagram letters portrayed Glover as a relatable character — one who embraces and gives voice to the everyday dilemmas fought by the average Joe or Jane. After being asked if his notes hinted at depression, Glover responded in an interview with People Magazine: “If I’m depressed, everybody’s depressed. I don’t think those feelings are that different from what everybody’s feeling.”

Rejecting the notion his notes were a cry for help, he instead insisted on their truth: that he is still a work in progress and carries the same fears and anxieties that many other people also carry. In that moment, he became our diffident antihero.

Of course, that a character who suffers from his or her own anxiety exists in entertainment today is nothing new. From Woody Allen's Alvy Singer (and just about all of his characters) to the socially inept Larry David, the anxious antihero has become a widely riffed caricature in our cinematic milieu. The difference, however, lies in the manner in which such a character is portrayed. Previous generations of self-effacing characters acted in and of themselves as the punch line. They articulate the things we know should in all likelihood remain as thoughts, and in doing so become laughingstocks. With diffident antiheroes, however, their world is the punch line, and they are the disassociated cog who exposes the brokenness of the machine. They reveal to us the often sad truth of, among other things, the modern condition, the nature of work and success, of self-actualization and self-esteem. And that's why we can relate to them. They are the ones brave enough to speak about deeply intimate and personal topics at a time when many of us are looking for someone to trust.

It is this thirst for honesty and authenticity that has led us to reconsider the archetypal hero we once admired. Now, it represents a doctored version of reality as inauthentic as the manipulated photos on the cover of fashion magazines, and more of us are choosing to find meaning not in those characters whose idealized lives are defined by their qualities, but in those realistic characters who are defined by their imperfections. We are looking for the characters who — like us — often play both the protagonist and the antagonist in their deeply complicated lives.