Advertisement

As AIDS Ravaged His Friends, Jim Hodges Made Art About Beauty And Loss

“People are dropping like flies,” artist Jim Hodges recently recalled of his experience of the 1980s to one of the co-curators of his big retrospective exhibition “Give More Than You Take” at Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art through Sept. 1, “and I am thinking, I am going to be next.”

Beauty, fragility and loss—especially loss—course through three decades of his art. It’s delicate art that conveys a sense that everything is precariousness, everything is fleeting, so embrace this lovely moment.

Hodges grew up the second of six kids in a Roman Catholic family in Spokane, Washington, then moved to New York (where he’s still based) in 1983 for grad school. A young gay man, he visited dance clubs and underground S&M bars, as AIDS ravaged his circle.

His response is a sort of alchemy that transforms common objects—scarves, necklaces, mirrors, denim—into ghosts and skulls, spiderwebs, cascading curtains of flowers, trees shedding their leaves.

The exhibition is part of what’s emerged as the ICA’s central focus on queer artists—Nick Cave, Amy Sillman, Steve Locke, Mickalene Thomas, Isaac Julien, Roni Horn, Mark Bradford, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, and the major survey of 1980s art “This Will Have Been,” organized by head curator Helen Molesworth, who is scheduled to leave to become head curator at Los Angeles’ Museum of Contemporary Art this September.

Hodges’s art is one of metaphors and allusions. But he often doesn’t clue you into the context to understand what he’s so reservedly pointing at. Which is part of why, his work often feels quiet, poetic, personal—and vague.

When it works, this art has the charge of flowers left on graves, lyrical and elegiac and autumnal. It feels like the work of a survivor, left to pick up the pieces in the silence after all that death—at times in mourning, at times ecstatic to still be experiencing the beauty of life.

After grad school, Hodges stopped painting. And he removed most colors from his art, working primarily in black and white, until around 1991, when he installed “Untitled (Gate)” in a New York alternative space gallery. Recreated here, it’s an 8- by 10-foot room painted evening blue. But you can’t enter because the doorway is blocked by a metal gate that serves as a frame for a spiderweb of heavy chains and, as it gets to the center, delicate necklaces. Charms dangle from the middle—a cat, a dragonfly, an elephant, a tyrannosaurus rex, a pharaoh, a butterfly. They seem specific symbols of specific things, but it’s unclear what. Perhaps certain friends? The gate feels like a door into the sky or heaven—but also a mausoleum.

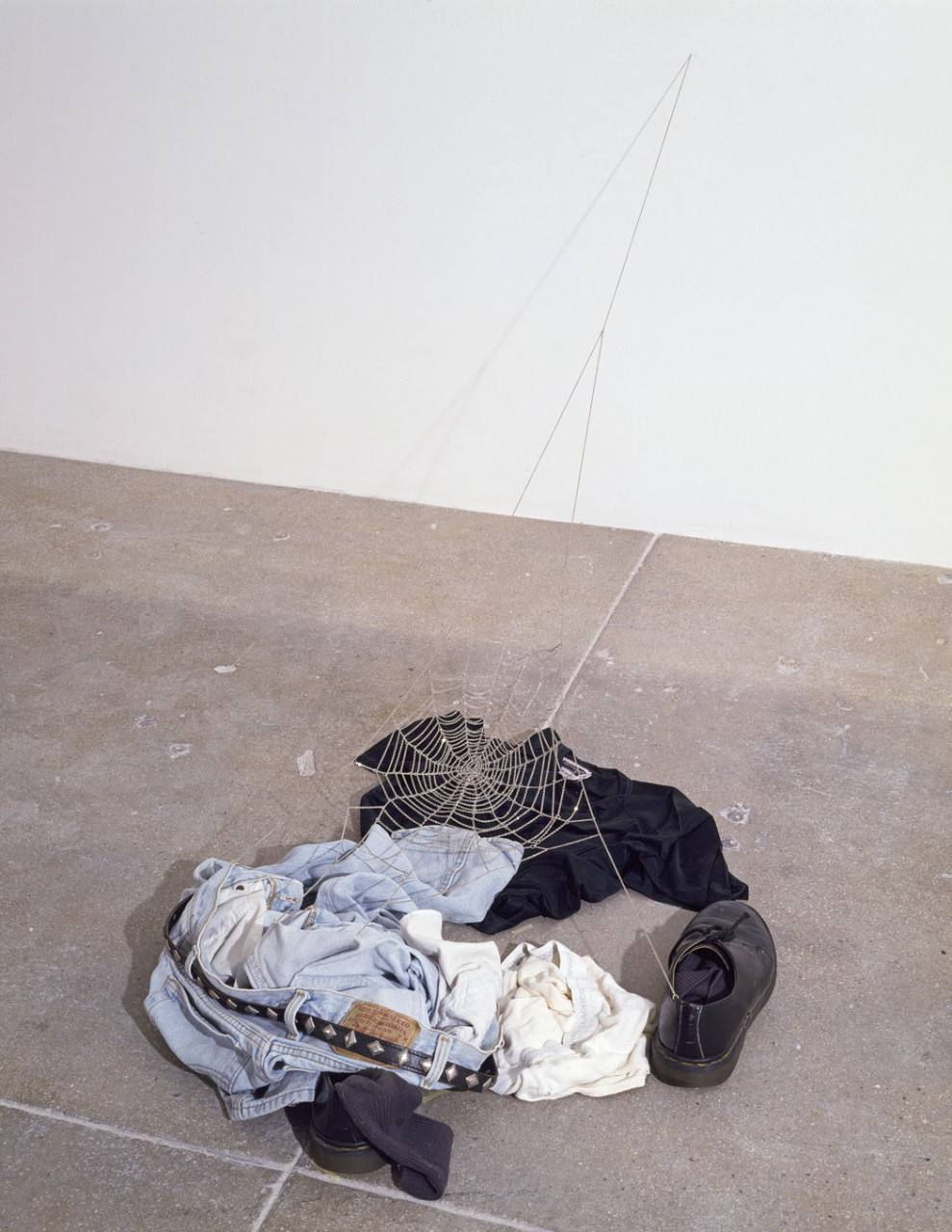

In Hodges’s 1992 installation, “what’s left,” a spiderweb made of brass chains is anchored on a pile of clothes (jeans, black T-shirt, socks stuffed into shoes) seemingly abandoned on the floor. Hodges has said he dressed up as if he were heading out for a night of clubbing, then stripped his clothes off to use in the piece. The web suggests they’ve been sitting there a while. And hints that the person is never coming back.

Hodges’s use of spectacle, suggested narrative, and pretty decoration align with the aesthetics of Catholicism, the AIDS era gay community, and the kinder gentler minimalism of peers—and friends—like Felix Gonzalez-Torres. The exhibition, which was organized by the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis and the Dallas Museum of Art, includes glass bells, broken mirrors, a strand of artificial flowers dangling from the ceiling, mirror mosaics that resemble flattened disco balls, camouflage fabric embroidered with falling flowers (from 2003, it seems to speak of 9/11 and war), a photo of trees with many of the leaves sliced out as if it were autumn, and a group of vividly colored sheer scarves, with little cut out butterflies and flowers stitched on.

Much of this stuff comes across as divertingly pleasant in the moment, but quickly evaporates from memory. Hodges’s art is ultimately conceptual—idea based—but he resists speaking directly about his subjects. When he doesn’t make feelings of loss or ecstasy clear, his intentionally light touch can just float away.

Hodges is most affecting when his allusions are most direct or his effects most spectacular. “Ghost,” from 2008, is a bell jar under which clear glass leaves sprout from colored glass earth crawling with spiders and butterflies. It seems like a spirit growing out of the decaying mulch on a forest floor.

That same year, he also produced “the dark gate,” a wood plank room that you can enter by a pair of swinging doors. The space is empty except for a small bare bulb in the ceiling. Opposite the doors is a wall of sharp metal spikes that frame a circle of air and hum with menace. The room feels like a shrine. The room feels like the passage between one world and the next. The room feels like the mouth of death.

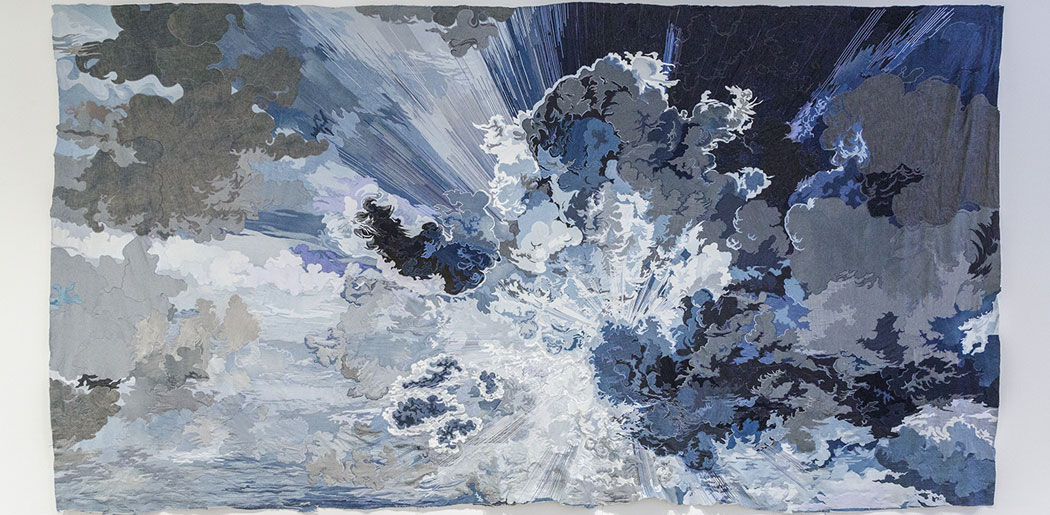

The newest piece in the show is a 24-foot wide crazy quilt of stitched together denim that he calls "Untitled (one day it all comes true)" (pictured at top). The handcraft involved impresses. (The museum reports that Hodges has a hand in everything, though like the glass plants, which were apparently made with help from a master glassworker, you suspect this is primarily the uncredited work of expert stitchers.) It’s a giant blue-on-blue scene of light breaking through clouds. There’s a bit of a paint-by-numbers roteness to the composition, but like landscape paintings by the 19th century Hudson River School gang, it has an ecstatic, sublime whoosh. It feels like the fresh, first light after a great storm.

Greg Cook is co-founder of WBUR’s ARTery. Let's talk about beauty and loss on Twitter @AestheticResear and Facebook.

This article was originally published on June 11, 2014.