Advertisement

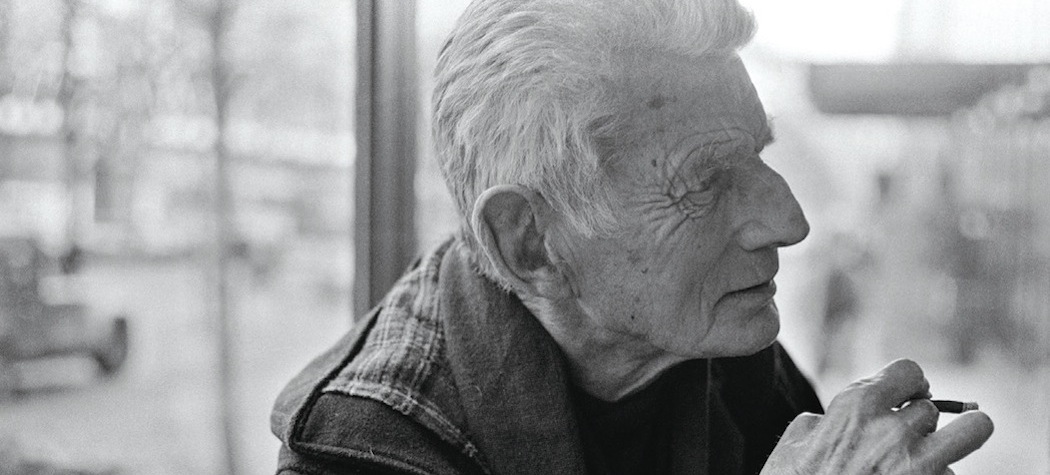

A Faint Echo: Samuel Beckett's 'Latest' Story Falls Short

“The dead die hard.” These are the opening words of “Echo’s Bones,” a short story by Samuel Beckett, 80 years in obsolescence and published now for the first time by Grove Atlantic Press. (122 pages, $22)

Evidently, the dead do not die hard enough.

After reading this tale from the crypt my take is that its publication adds little to the canon of this Nobel Prize winner. Beckett’s own view of the story — while writing it — was even less felicitous: “[I]t is all jigsaw and I am not interested,” he wrote to his friend Thomas MacGreevy.

Beckett scholar Mark Nixon, who edited the new book, even warns readers in the introduction that the story is “obscure,” “uneven in tone and mood” and “evasive in stating its business.” It’s hard to believe the man who would bring to the stage 20 years later the world-shaking "Waiting for Godot" would earn such a review — from a friendly party, no less.

More compelling than most of “Echo’s Bones” is the story behind it. Beckett’s wonderfully titled first foray into fiction, "More Pricks than Kicks," was a collection of 10 interrelated stories that was accepted by the London publisher, Chatto & Windus, in September 1933. Feeling it needed a bit more heft, his editor, Charles Prentice, concluded the acceptance letter with “Hurray too if you manage that extra story.” The problem was, or would have seemed to be, that Beckett had killed off his protagonist, Belacqua, in the penultimate story of the collection proper.

However, eager for success, Beckett acquiesced and struggled to write “Echo’s Bones,” calling Belacqua back, Lazarus like, and running him through a triumvirate of interactions. That November, Prentice wrote to Beckett upon his reception of the story, now named “Echo’s Bones,” after Ovid’s poem about Narcissus and the mountain nymph, claiming: “It’s a nightmare… It gives me the jim-jams.” From the letter, reprinted in the back of the new edition with others, Prentice was clearly trying to be diplomatic toward his new author. The story was shelved all these decades and dusted off for this first printing, which was years in the making.

Now, the nightmare is ours. To be fair, the story is rarely dull, and the final third of the tale actually gains some narrative momentum, even if it relates to little that went before. And what went before is too Joycean for its or anyone’s good. Like his mentor, who when he wrote "Ulysses" tried to pour into it everything he knew, Beckett makes a pot-puree of “Echo’s Bones.” Each page features multiple allusions, from sources as diverse as St. Augustine, a book by Robert Burton called "The Anatomy of Melancholy," Shakespeare, the Bible, Dante, Irish and world history, mythology and much more. Each is gratefully annotated in the nearly 60 pages of end notes for those who really want to get lost in the density of these pages.

The triptych of narratives, if one can call them that, initially features the risen Belacqua being accosted by a prostitute. When she inquires if during his trip through the afterlife he has learned whether there is a God, Belacqua replies, “Presumably,” before admitting: “I know no more than I did.” Next, he has a go with both an impotent giant named Lord Gall and, later, his wife. And finally, Belacqua meets Doyle, a grave robber, intent on digging up his coffin while Belacqua himself looks on and bets him it’ll be empty. “I sometimes wonder whether death is not the greatest swindle of modern times,” he tells the shovel-wielding Doyle. What will be found in the coffin serves as a MacGuffin of sorts during these final pages, at last giving a focus to the narrative.

Gems occasionally poke their way through the prose, such as: “Women in particular seem most mutable, houses of infamous possibilities.” Add the puns, self-referential asides and meta-fictional touches (the giant Lord Gall tells Belacqua to repeat something but with “No style!”) and “Echo’s Bones” struggles to redeem itself. But ultimately, “Echo’s Bones” should be left to the scholars and anyone interested in tracing the development of this formidable writer. In its 13,500 words we don’t get Beckett the minimalist master of the coming years, but a writer still caught in Joyce’s shadow, but clearly on his way to becoming something truly original.

John Winters teaches and works at Bridgewater State University. More of his writing is at johnjwinters.com.