Advertisement

There Will Always Be An England — In The Berkshires

PITTSFIELD, Mass. – English theater has a hold on the American imagination the way that American cinema does on the world’s consciousness. There’s something about the way they construct plays that seems to be less of the moment, even when the subject is housing in the 1970s (“Benefactors” at the Berkshire Theatre Group) or persecution of a war hero in the 1950s for being gay (“Breaking the Code” at Barrington Stage Company).

No one’s plays are more timeless than Shakespeare’s and he is ably represented in the Berkshires every summer by Shakespeare & Company, who are doing “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” set in New Orleans and “Julius Caesar” set back in the Roman era — of all things.

There’s a tight relationship of the personal and political in all these plays, but the most fascinating is in the superb Barrington Stage production of “Breaking the Code,” about the life of Alan Turing, the instrumental code-breaker in the Enigma project. Not shy about his mathematical abilities he claimed that England would have lost the war without him — there’s little doubt that he saved millions of lives.

That didn’t stop the English authorities from going after him for being gay, or at least being open about it under the Gross Indecency laws, the same that ruined the life of Oscar Wilde. Turing had little in common with Wilde, though, at least as depicted in the play. He was a stutterer, uncomfortable in his skin, and if he was forthcoming with the police it wasn’t to make a political statement, but to assert the mathematical near-certainty of his position. I saved England, I am a biological homosexual, ergo why would England prosecute me.

While that is all part of the takeaway from “Breaking the Code,” Whitemore goes deeper into Turing’s psyche. As in Tom Stoppard’s “Arcadia” or Michael Frayn’s “Copenhagen,” there is a sometimes-dizzying aspect in squaring the circle of Turing’s mathematical prowess (which slips into philosophy), his personal tics and the repressive English politics.

It’s hardly a paean to Turing as a historical gay icon, though. While Whitemore is clearly on the side of the angels here, he’s constantly asking, and forcing us to ask, whether Turing was being foolish about pressing the issue. Should he have gone to the police when he was robbed, probably by a lover? Should he have blurted out that he was gay? The officials seemed to prefer a don’t ask, don’t tell policy that is anathema to us now, but perhaps discretion was the better part of valor in the 1950s? Preferable, at least, to suicide.

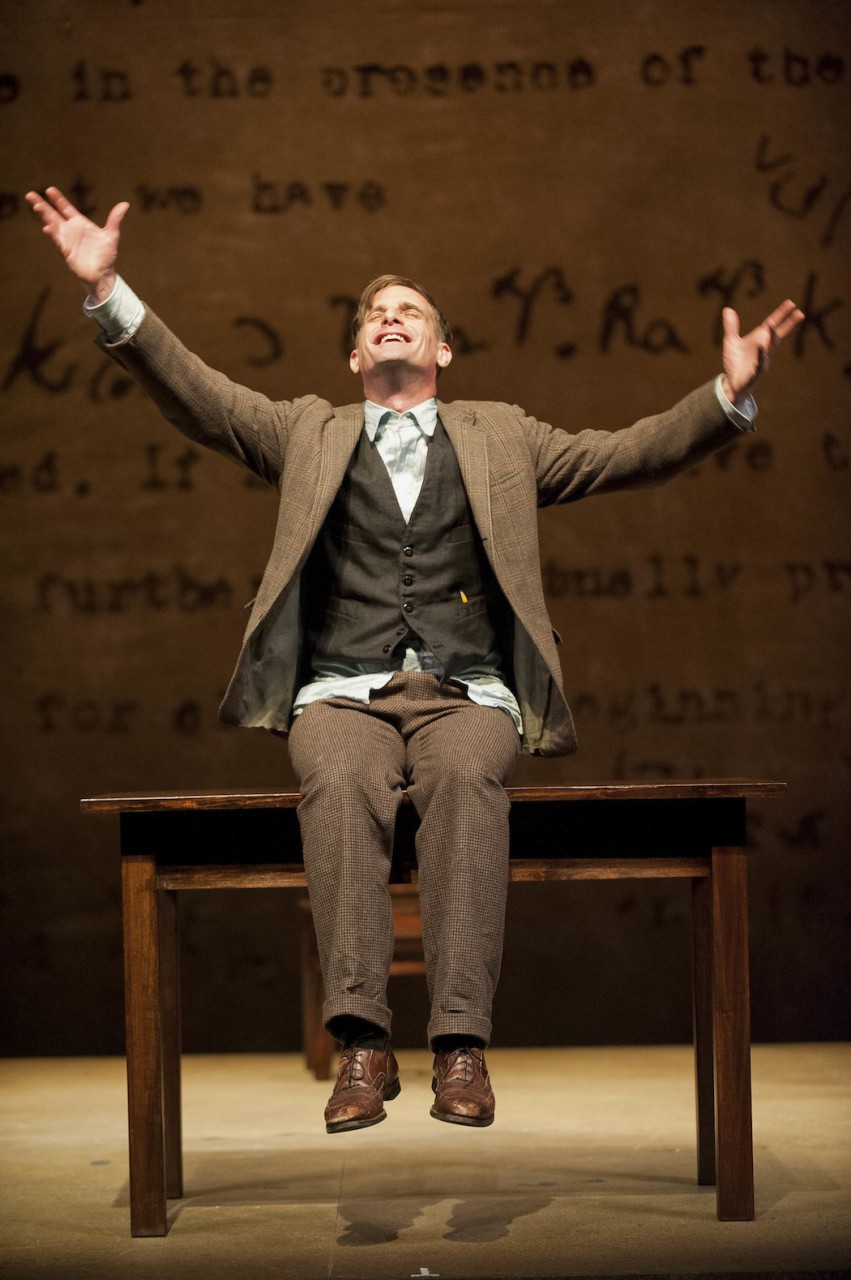

Turing, who was also one of the developers of the computer, knew that uncertainty was part of any principle, but seemed to lack the common sense to include the human factor in his equations. Mark H. Dold is an amazing Turing, never knowing where to put his hands or even how to conduct a basic conversation with people. (I prefer it to Derek Jacobi’s. Unfortunately, I missed Allyn Burrows in the role at Underground Railway Theatre.)

Equally stunning is Joe Calarco's direction. The stage is barely adorned, with actors sitting on the sides watching events unfold, until scrims of mathematical equations are lit, creating a world of its own — confining and liberating at the same time. To Turing it was a beautiful, self-contained world and he was a hero in it. But tragic heroes have fatal flaws and Turing was no different.

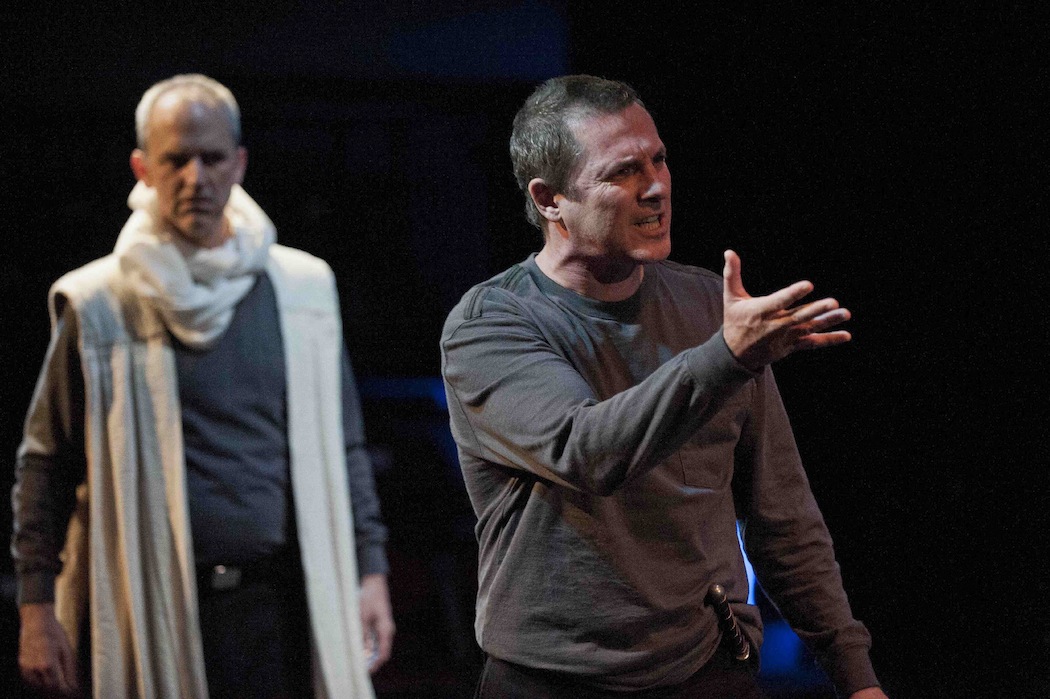

Shakespeare knew a thing or two about tragic heroes and conventional wisdom has it that Brutus is the tragic hero of “Julius Caesar,” rather than the title character. But in Tina Packer’s “Bare Bard” seven-actor production at the smaller Bernstein Theatre at Shakespeare & Company in Lenox, we’re in a world without heroes. Self-aggrandizement vies with self-righteousness at every turn.

In fact, the central character here is Cassius, neither lean nor hungry, but a raging bull, convinced with Tea Party fervor that Caesar is a dictator and that the only way of liberating Rome is to impeach him — with knives. Jason Asprey’s scintillating Cassius pretty much owns this production.

Part of that stems from the absence of Nigel Gore until Aug. 9. Dennis Krausnick is a dependable actor, even if he stumbles over lines, but he’s no Gore, and his Caesar doesn’t have much stature.

The main problem, though, is Eric Tucker’s Brutus. This is a family-affair production for Packer. Krausnick is her husband, Asprey her son from another marriage, Gore her costar in “Women of Will” and other shows, and Tucker was the director of the acclaimed New York production.

The artistic director of Bedlam in New York, Tucker has never been my favorite Shakespearean actor. He was a weak Iago 15 years ago and an even weaker Cassius — all affect with squinty eyes, Kirk Douglas teeth and weak-willed forward movement. Packer might want a world without heroes, but Brutus is just a bore.

That said, it’s an engaging staging, as are almost all of Packer’s productions. It grabs you by the lapels and makes you listen to Shakespeare with fresh ears — I grew up learning Antony was the hero of the play. It’s obvious, here, that he’s as Machiavellian as anyone else. James Udom as Antony and the rest of the cast all have a way with Shakespearean verse, none more so than Kristin Wold in a variety of roles. (She’s also playing Anne Hathaway in the one-woman show, “Shakespeare’s Will.”) Packer’s work with movement director Victoria Rhoades is exquisite.

A Midsummer Night's Dream

Packer is the founder of the company and had been its artistic director until 2009 when she turned over the artistic reins to Tony Simotes who, ironically, is holding forth at the Tina Packer Playhouse with “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.”

He’s not the only one holding forth. I know, you’ve seen it a million times, but Simotes and company have a blast in jazz-era New Orleans with this one. He’s a less overtly political director than Packer, but no less interested in text-driven, psychologically astute productions with more than a hint of spectacle.

Rocco Sisto and Merritt Janson might not be the most age-appropriate king and queen of the fairies, Oberon and Titania, but they’re both so comfortable in their roles, that it’s little matter. Jonathan Epstein’s Nawlins drawl is a hoot — as are all the Rude Mechanicals — and it’s a delight to see local favorite Johnny Lee Davenport as Bottom. Speaking of local favorites, Company One alumna Cloteal L. Horne deserves a shoutout as a Helena you don’t want to mess around with. The four lovers are such gifted comedians — I’m sure Simotes had something to do with that, too — that the Pyramus and Thisbe comedic ending is almost beside the point.

“A Midsummer Night’s Dream” is hardly the most political play Shakespeare wrote, but there is an air of rebellion against authority in the air and a sense that the other-worldliness of the forest is antidote to the repressiveness of the political authority. And when they break into a chorus of “I’ll Fly Away” you might just want to join in their release.

Benefactors

Michael Frayn’s “Benefactors” at the Berkshire Theatre Group's smaller Unicorn stage in Stockbridge is the curiosity among these plays. Although the politics of the 1984 play still matter, the people don’t. David, an architect, wants to build a twin-tower apartment complex that will reach to the heavens, simultaneously solving a low-income housing problem and preserving his fame in his field.

They’re looking back in the play from the Thatcher ‘80s to the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. Idealism is in the air and each character has a share of it. Except for David’s wife, Jane, though, the four characters are also so lost in their little worlds that they defy credibility.

They are “friends” but David can’t see that Colin has it in for him or that Sheila is in love with him. Sheila is a hopeless romantic and a dishrag of a wife. And Colin is such a grotesque self-absorbed sexist turned left-wing activist that you’d think Ann Coulter wrote the character.

I don’t know that Walton Wilson does the play any favors by making every gesture such an example of porcine behavior. Director Eric Hill and the company of actors — David Adkins, Corinna May, Barbara Sims and Wilson — are all talented theater folk and the politics of housing and the ethics of compromise are very much with us today. The four characters all wrestle with the notion of liberal ideals giving way to more personal rewards, and people still grapple with those competing claims on the psyche. But Frayn was able to square the circle when it came to the personal, political and philosophical in “Copenhagen” in a way that seems to have eluded him here, at least to judge from this production.