Advertisement

Is Amanda Palmer Asking, And Sharing, Too Much?

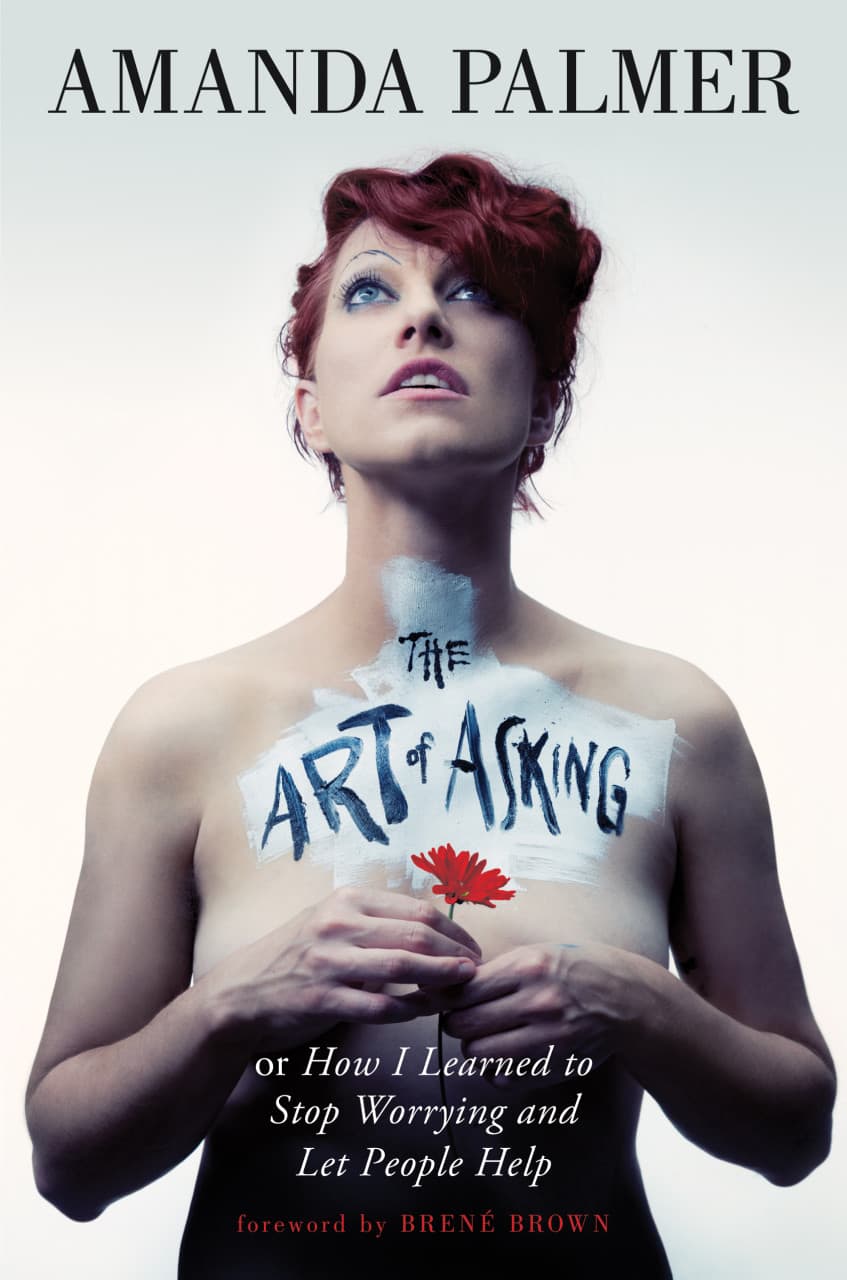

Amanda Palmer is not her book. Granted, anything written by a celebrity will be viewed in light of that star’s brilliance. If the work is memoir or self-help — or a so-called manifesto explaining the author’s approach to art/life/love — even more so. In the case of Palmer, whose new “The Art of Asking, or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Let Other People Help” sprang from a TED talk combining all of the above, it’s particularly difficult to judge the book without seeming to judge the person.

The Lexington-raised Palmer has built a career on standing out. Literally, in the case of her first real artistic success — the Eight-Foot Bride. As a white-faced, wedding gown-clad street mime in the late ’90s, Palmer towered above the passing crowds in Harvard Square, silently handing out flowers in exchange for donations. This act, she writes, embodied the artistic transaction. “Thank you … I see you.” A mirroring that validated both the performer and the recipient of her day-old blossoms.

It also, she claims, taught her how to be vulnerable — how to ask. For that validation, certainly, but also for money and for the kind of extra attention that allows artist and audience to, as the author says, “enrealen each other.” (Italics are hers.) This proved useful when her self-consciously edgy music took center stage, first as the Dresden Dolls and later in a variety of other forms, both solo and in collaboration, and Palmer fretted at the constraints of the recording industry.

The composer of smart, tuneful pop, Palmer has long stressed the personal nature of her music – speaking not only about the autobiographical basis of many of her songs but also about her relationship with the fans who have supported her. It’s a relationship that has, in recent years, been strained.

Palmer, who performs at Royale Tuesday night, is no stranger to controversy. Her onstage persona is intentionally provocative — sexual and in-your-face — and much of the criticism she has confronted reeks of misogyny, insulting her body and stage-y makeup as much as her music. A polarizing performer, she is quite aware of the furor she incites. Indeed, in the book she seems to revel in one particular slur — the Dresden Dolls were called “the gay mime band” — as a badge of honor.

A critical success onstage, she has courted the spotlight offstage with wildly mixed results. The most infamous of these came when, shortly after the Boston Marathon bombing in 2013, Palmer posted “A Poem for Dzhokhar” on her blog, a stream-of-consciousness free verse from the accused bomber’s perspective that quickly garnered an avalanche of attention — much of it angry and even threatening.

Discussing the incident here, she sounds shocked by the severity of the reaction. How hurt she was by it, even as she makes the case for what was, at best, a tone-deaf move. “To erase the possibility of empathy is to erase the possibility of understanding,” she writes. “This is what art does. Good or bad it imagines the insides, the heart of the other, whether that heart is full of light or trapped in darkness.” It’s a better defense than the poem merits.

She is less adept — and less candid — when dealing with a more fundamental controversy. In 2012, Palmer announced a Kickstarter campaign to raise funds for a new recording. Her fans responded, raising nearly $1.2 million in exchange for pre-orders of the album. All was well and good until Palmer then resorted to her standard modus operandi of inviting fans who were also musicians to join her on stage for the subsequent tour — without pay.

The backlash was perhaps not as vitriolic as that which her “A Poem for Dzhokhar” would provoke, but it hit closer to home. Despite Palmer’s explanations that the money raised was going into the recording, the sheer amount fueled the ire. And in many ways, this book reads like an in-depth response to that anger, returning repeatedly to the nature of collaboration and the open relationship she seeks to maintain with her audience. Ultimately, Palmer backtracked, agreeing to pay those who performed with her.

The subject is clearly still a tender one, and Palmer dodges it. In addition to backloading her argument about collaboration, she also blames the backlash on “the press,” a slagging off that can only be seen as disingenuous from someone this savvy in the ways of social media. No, it wasn’t journalists who raised the hue and cry; it was the public. Artistic vulnerability goes both ways: if you ask, you have to be receptive to the answer.

That’s not the only problem here. I count myself a fan of Palmer’s music, despite her occasional missteps, in part because she puts so much of herself out there. But also, because of her discipline and skill. The music she gives us is catchy as hell, and her lyrics are often funny and literate. However, a deft hand with lyrics does not necessarily translate into long-form prose. At least, it doesn’t here.

To say Palmer overshares is almost a tautology. That is what she does, and it is to the credit of her husband, the author Neil Gaiman, that he has apparently agreed to the scenes depicted here, the “innermost personal details,” which range from a terminated pregnancy to various tantrums about money and art.

It’s not what she writes about; it’s how. Too often, she relies on the kind of unspecified gushing that I doubt would make it into one of her tightly crafted songs. “I wanted to French kiss every floorboard and mismatched doorknob,” she writes of her first encounter with the artist’s haven where she rents an apartment. For every fine description — of the joy of crowdsurfing, for example — there’s a clumsy neologism or usage: “enrealen,” “upheaved.”

And for all her celebrated candor, there’s still that subtle shading — the evasion, the misdirection, the vague references to suspiciously adoring fans (or newly won-over enemies, like the masseuse who gives Palmer “the Birthday Massage of Absolution”). These do little to explain the evolution of the artist, but much to gloss the narcissistic tone of this overlong work. This bias comes across not so much as dishonesty — though it could be called that — as a failure of nerve, from an artist who has built a career on anything but.