Advertisement

From Medford High To UVA — Why Football Still Matters To Scholar Mark Edmundson

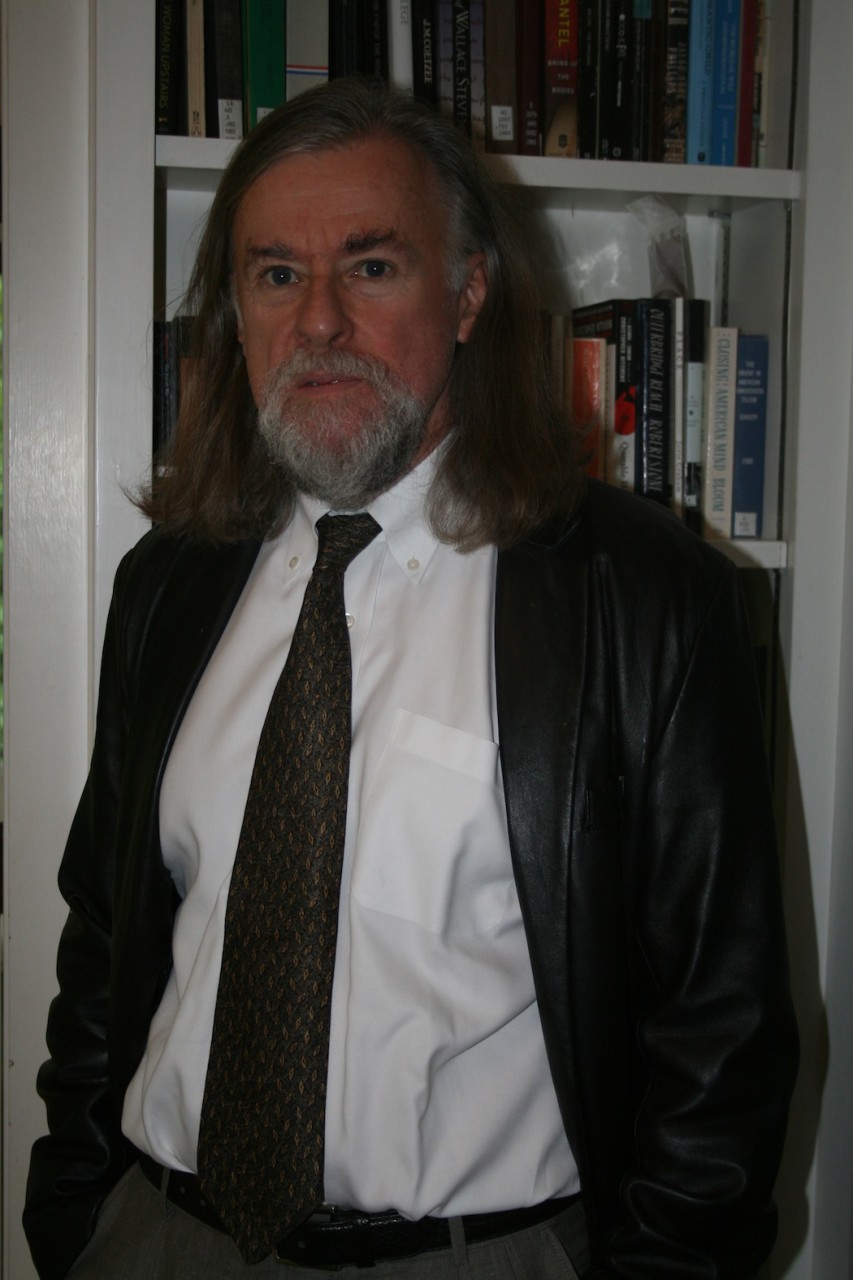

I’ve felt a kinship with Mark Edmundson ever since reading his 1997 book, “Nightmare on Main Street,” a brilliant analysis of the Gothic strain in American culture. As a fellow horror fan I was struck not only by the play on “Nightmare on Elm Street,” but by his ability to translate that interest into so many other areas I care about, from phony pop transcendence in movies like “Forrest Gump” to intimations of the real thing in “Angels in America.”

Then I found that the University of Virginia English professor had written a book called “Teacher,” about how a Medford High School philosophy teacher, Frank Lears, had changed his life. Having moved to Medford, not only did it resonate with me geographically, but it reminded me how a Boston Latin School English teacher, Joseph McNamara, had changed mine.

“My father saw something greater than himself [in football] and he loved it -- and he tried to teach me to do the same.”

Mark Edmundson

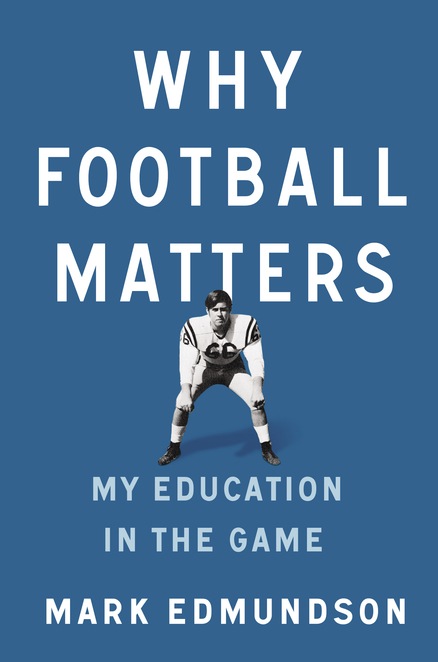

Edmundson has also written several distinguished books and essays for the likes of the New York Times and Harper’s, including some of the smartest work you’ll find on Sigmund Freud anywhere, so it was a bit of surprise that his latest book is “Why Football Matters,” charting his appreciation of the game as both a fan and as a player with the Medford High Mustangs.

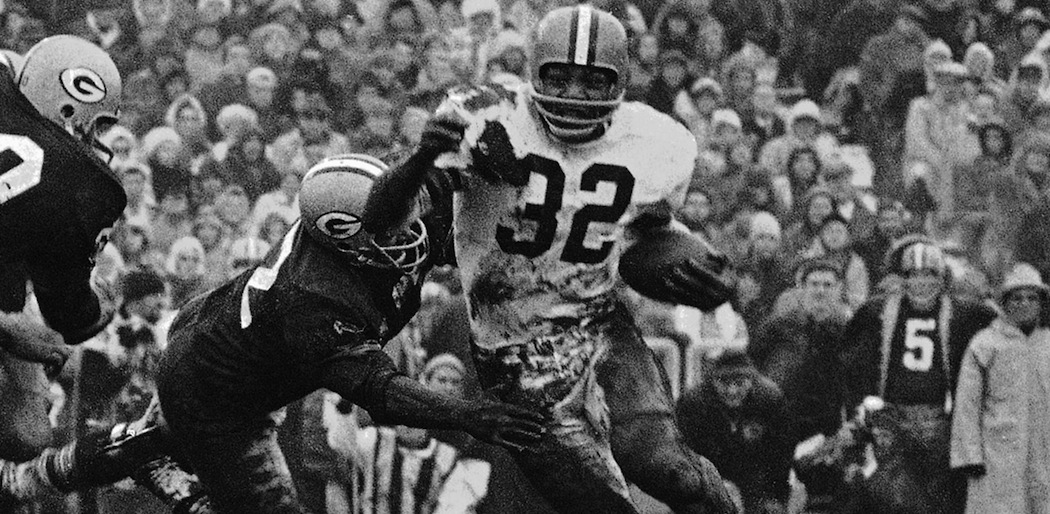

It also turns out that we both bonded with our fathers watching Jim Brown, the great ‘50s and '60s star of the Cleveland Browns when he carried would-be tacklers with him in the pre-Patriots National Football League. “My father saw something greater than himself on the screen and he loved it — and he tried to teach me to do the same,” he writes.

"Go back to the Greek. Football stirs up thumos — passion, energy. It can be put to good uses but it can go south pretty darn quickly. Guys who play football have the capacity for intense work, the capacity to work together, to work toward a goal. But that intensity can break in either of a couple of different ways, good and bad."

Mark Edmundson

Truth be told, the Edmundsons were really fans of Y.A. Tittle and the hated New York Giants, or as their blowhard announcer, Chris Schenkel, called them, the New York Football Giants, but his father made an exception for Brown. Edmundson would later go on to have a memorable, if not Jim Brown-like, couple of years with the Medford Mustangs football team. (The closest I came to “Glory Days” was intramural bowling. Candlepin.)

Those years with the Mustangs also changed Edmundson’s life, and he believes it was for the better — even though he acknowledges almost all the shortcomings of football that WBUR colleague Steve Almond writes about in “Against Football,” which Edmundson admires.

In fact, “Why Football Matters” can be read as an internal, philosophical dialogue between pigskin positives and negatives. Fear not, though. Even though Plato pops up in the book — this might be the first football book that references Plato and poet Elizabeth Bishop — “Why Football Matters” is as accessible and high-spirited as all of Edmundson’s writing.

Yes, says Edmundson I, football builds character among those who play it. But then, says Edmundson II, character isn’t all it’s cracked up to be: “What we call character can be the enemy of imagination, empathy, invention, and of plain, pleasant dreaminess.”

That duality begins with Mr. Plato himself, says Edmundson in the book:

“For football is what Plato calls a pharmakon, a poison and an elixir. Football can do great good: build the body, create a stronger, more resilient will, impart confidence, stimulate bravery, and cultivate loyalty. If I hadn’t played football, my life would have been different and (I’m nearly sure) poorer than it had been …

“But football is a dangerous game. The chance of concussion is constant; the repercussions last for a long time … There is risk to the spirit as well … Football can brutalize a man. It can make him more aggressive, even violent …

“The game can make a player intolerant of gentleness. It can help turn him into a member of a pack that mistreats and even scapegoats others — the weak, the differently made. The game can make men unthinking; their football-based character often seals them off from real reflection … And football’s merger with religion, especially Christianity, isn’t far short of ridiculous. Does Jesus really care if Medford beats Everett?”

So all that said, why does football matter? We caught up with Edmundson by phone in his Charlottesville, Va., digs. When he thinks of how Plato and Y.A. Tittle, or Frank Lears and the Medford Mustangs, changed his life, are the football and philosophy gods two different aspects of his personality or is it more integrated than that?

“That was one of the reasons for writing the book as I came to the conclusion that [philosophy and football] were more integrated than I thought. I moved from a football jock world to an academic work world. But writing an essay or a book takes a lot of qualities I cultivated from football. Doctors and lawyers will tell you the same, they’re better doctors or lawyers because of football.”

The discipline and teamwork, the trying and failing that often leads to trying and succeeding, all can lead to a more disciplined and team-oriented approach to work and life, says Edmundson, though it’s hardly a universal. Witness ex-Baltimore Raven running back Ray Rice.

“It was a pretty horrible story,” says Edmundson of Rice. “I was blown away by the video of him beating his wife, but not that surprised. Go back to the Greek. Football stirs up thumos — passion, energy. It can be put to good uses but it can go south pretty darn quickly. Guys who play football have the capacity for intense work, the capacity to work together, to work toward a goal. But that intensity can break in either of a couple of different ways, good and bad.” Even Jim Brown turned out not to be the distinguished warrior we thought growing up, as much a merciless, machismo-ridden Achilles as a thoughtful, humane Hector, in Edmundson’s breakdown of bravery and character.

And what about football from the spectators’ view? Why do Americans veer toward football, while the rest of the world goes to soccer? It’s not just the Romans watching the gladiators, he says. “We like seeing people do things that are risky, dangerous … and beautiful. But what they’re doing also functions as part of a group goal. Guys out there doing something really brave — not as brave as soldiers — but we're not as conflicted toward football as we are toward war."

“Soccer emphasizes the beauty of game, though I don’t have a great read on soccer. If they widened the goal by six feet and score was 6-3, instead of 1-0, it would probably be more popular here. But the game’s fans feel soccer interprets the truth of life better than football. You mount an attack and fail. You do succeed, but only occasionally. Basketball, on the other hand, is promiscuous, orgiastic. Somebody succeeds every minute.”

Edmundson is still a football fan, though his allegiances have shifted from the New York Giants to the New England Patriots and to the UVA Cavaliers. He shares the concern about the UVA fraternities, even as he shares in the condemnation of the horrible journalism involved in the Rolling Stone story told from one woman’s perspective (without checking on her credibility or hearing from the accused).

“If I were the managing editor, I wouldn't vacation in Charlottesville any time soon. There’s a lot of confusion and waiting for the potential accuracy of what happened and didn't. Is there really a problem at UVA? If so, how deep and if so, how to remedy it? I think we’re all grateful for the cooling off period as the school closes for the holidays. But [UVA president] Terry Sullivan is going to have to decide about re-opening the fraternities soon.” [The suspension of the fraternities lasts until Jan. 9.]

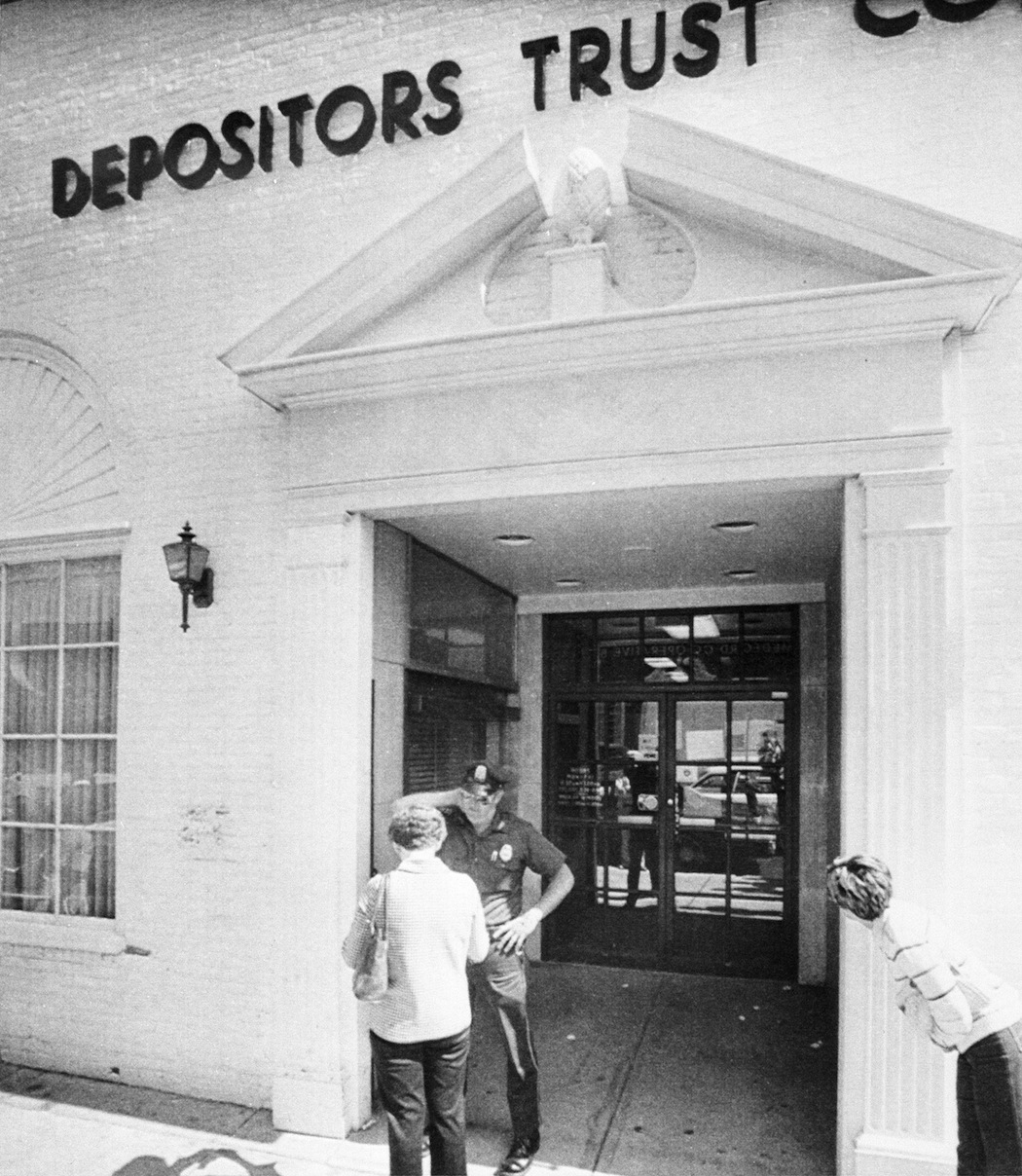

Edmundson is more lighthearted about his native Malden and Medford, where the family moved when he was in the eighth grade. All Medfordians have a black-humored love of the lore in regard to how Medford and MDC police officers broke into a Medford Square bank vault in 1980 and robbed it of over $1.5 million. He feigns disappointment, though, when I tell him that the police department now seems well-run and that the vault door leads to a private dining area in Salvatore’s Medford Square restaurant.

But there’s a duality here, too. Edmundson acknowledges that “No old people want things to change. It’s depressing that the cops are now honest” he laughs. (He’s 62.) On the other hand, he acknowledges that change is good, particularly for the new communities who make his native Malden their home.

“Who knew, growing up there that Malden would soon be lived in by Cambodians, Haitians, all kinds of people. It’s kind of fantastic, really. It’s pretty great.” Even if his elementary school, Belmont School, is now a condo.

Oh, and by the way, Edmundson points out that last Thanksgiving Day Medford High beat Malden for the first time since 2006. And, I had to note back, Boston Latin was also victorious, avenging the previous year’s loss to Boston English.

For whatever reasons, football still matters.