Advertisement

2014 Books: Gawande And Ferrante, McEwan And McBride

What’s the equivalent of a page-turner in the ebook universe? A thumb-presser? A swift-swiper?

Doesn’t have the ring to it, does it, so let’s keep page-turner, particularly since old-school reading is still more enjoyable than Kindles and iPads, even if tougher on the arms and the bookshelves.

So here’s what kept ARTery reviewers turning pages most rapidly in 2014. May there be more like them in the coming year.

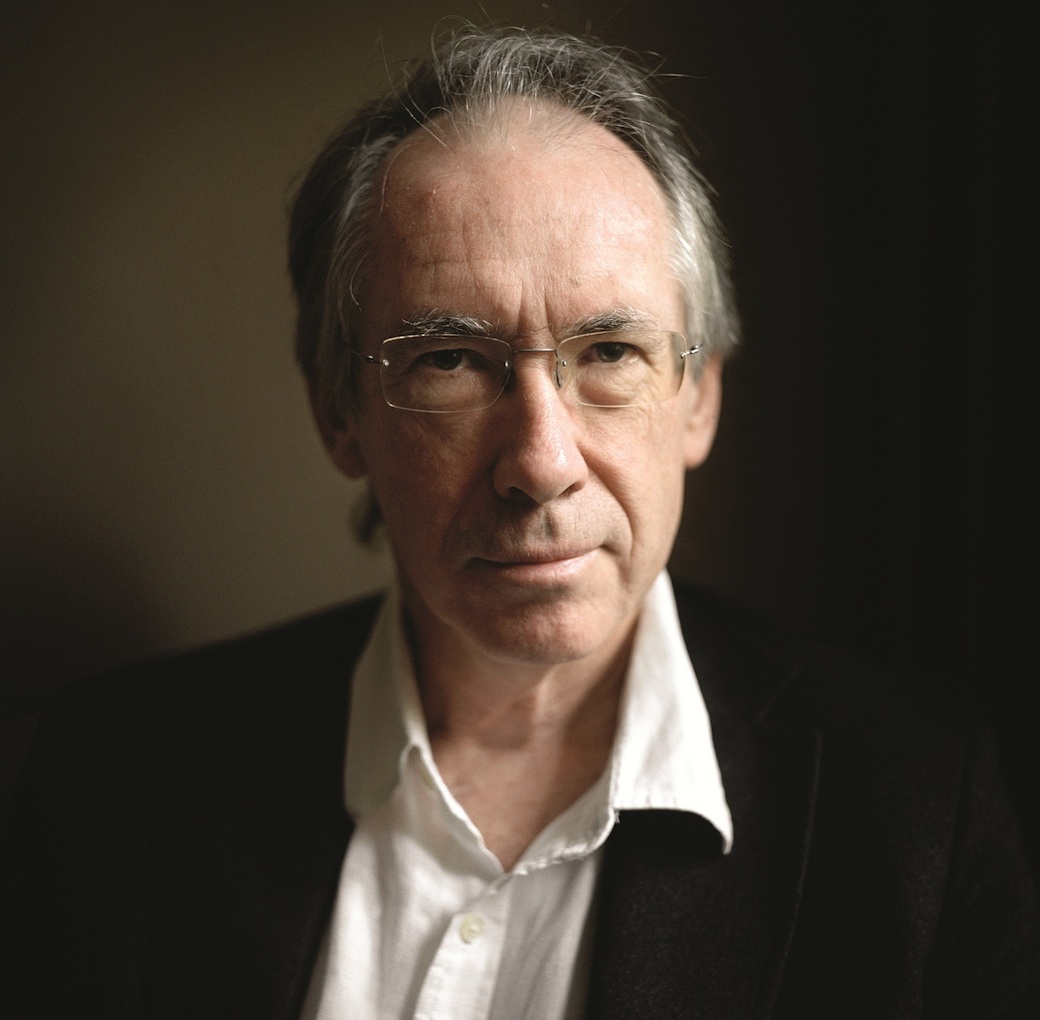

Someday I’ll understand the pockets of American antipathy to Ian McEwan, but certainly not this year. “The Children Act” is such a marvelous read, centering on a judge whose husband has just announced he’s leaving her, but who has to put that aside to rule on a young Jehovah’s Witness who will die of leukemia if he isn’t given a transfusion. Although McEwan is a lefty in good standing, his politics are never imposed on his riveting stories and multi-edged characters. The scene where the two main characters perform Britten’s adaptation of Yeats’s “The Salley Gardens” together is equal parts heartbreaking and life-affirming.

I know, “The Goldfinch” was written in 2013, but it took the Pulitzer announcement to get me to give Donna Tartt a try. And what a wild neo-Dickensian ride it is, from the bombing that takes the life of the protagonist’s mother to his relationship with a Russian artful dodger, Tartt captures the devastating realities of life in 21st Century America and the salvation that very few things besides art can deliver.

Two of my ex-colleagues at the Boston Globe are more dazzling than ever. Gail Caldwell writes about her life with such grace, lack of sentimentality and insight that she could probably make boiling water spellbinding. She has much more interesting fish to boil — polio, for example, and the love of a good dog — in “New Life, No Instructions.” And Vicki Croke, now a WBUR colleague, tells a jaw-dropping story in “Elephant Company,” about James Howard “Elephant Bill” Williams’s love of a good elephant and how that was put into use in World War II. It’s also a terrific piece of writing.

Ruth Rendell, “The Girl Next Door,” and Benjamin Black, “The Black-Eyed Blonde.” You can teach an older writer new tricks. Rendell, now in her 80s, has decided that she’s not going to just let the youngfolk

have all the fun. It’s time for 70 and 80somethings to enjoy sex — and maybe murder — in her latest mystery about a pair of discovered hands reuniting some old friends and lovers. And it wasn’t enough for John Banville to adopt an alter ego in mystery writer Benjamin Black, but now Black has developed an alter ego in a Raymond-Chandler style Philip Marlowe adventure, "The Black-Eyed Blonde." These aren’t the best works by these writers, but they’re great reads in their own right.

--ED SIEGEL

The Library of America has produced two books that ought to make music lovers very happy. One is “Music Chronicles 1949-1954,” an outstandingly readable collection of the writings on music by composer and Herald Tribune music critic Virgil Thomson, edited by USC professor and Pulitzer Prize-winning music critic Tim Page. I opened it at random and found a previously uncollected essay from 1952 called “Don Carlo and the Pickets,” about a group of ill-informed picketers protesting the Met’s production of Verdi’s masterpiece on the grounds that it was pro-Communist and anti-religious. It reminded me of the brouhaha over the recent Met production of John Adams’s “The Death of Klinghoffer,” in which many protesters admitted to never having heard the work they were picketing. I love Thomson’s response to the idea that the Met was run by Communists who were distorting Verdi for their own nefarious purposes: “One would have to look far for an institution more thoroughly in the hands of capitalists, their sons and daughters, their wives, their widows, and their lawyers.”

Another satirical view of the Met is part of LoA’s two-volume set edited by musical theater expert Laurence Maslon — “American Musicals: The Complete Book & Lyrics of Sixteen Broadway Classics.” The rarest of them is the 1933 topical revue by Irving Berlin and Moss Hart, “As Thousands Cheer,” whose second act begins with a skit about commercials interrupting radio broadcasts from the Met. That show is best remembered for introducing “Easter Parade” and for the great Ethel Waters singing “Heat Wave” (“She started a heat wave, By making her seat wave”) and the heartbreaking “Supper Time,” about the widow of a lynching victim. Two of the best musicals—“Show Boat” and “Pal Joey”—are in newly restored versions. Some of the choices are inevitable: “Kiss Me Kate,” “My Fair Lady,” “Gypsy”. Others make me want to argue. Why choose Stephen Sondheim’s “A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum” over his more groundbreaking “Company?” Why leave out Rodgers and Hammerstein’s greatest musical, “Carousel,” or “West Side Story,” or anything involving the Gershwins? Still, with its dazzling pages of theater photos, these are volumes to treasure.

Former poet laureate, Pulitzer Prize-winner, and Cambridge resident Louise Glück’s latest book, “Faithful and Virtuous Night” just won the National Book Award for poetry. I think it’s one of her most haunting and gripping accomplishments, the latest unpredictable masterwork from one of our most treasured writers. It’s a kind of fictional autobiography—or autobiographical allegory. The poems are mostly in the voice of an old man, an English painter looking back over his entire life—his obsessions and sacrifices. The title is actually a pun, the artist remembering what he mis-heard as a child when his older brother was reading to him about a faithful and virtuous knight. But of course, the title also suggests an inescapable and companionable darkness, the inevitability, the proximity of death. When Glück, clearly astonished, accepted the National Book Award, she said, characteristically: “It’s very difficult to lose (I’ve lost many times), and it also, it turns out, is very difficult to win.” This paradox is one of the undercurrents of all her writing, and it’s perhaps expressed most poignantly in this extraordinary new book.

-- LLOYD SCHWARTZ

How do we create safe and meaningful final years? Ultimately, how do we want to die? In “Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End,” Atul Gawande addresses these questions with thoughtful originality, the same fresh thinking that underpins his New Yorker articles and previous books — notably, “The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right.” Smart and compassionate, “Being Mortal” is a masterwork that will inspire new, and markedly better, views of the end of life.

-- CAROL IACIOFANO

“Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay,” Elena Ferrante. The third of the author’s Neapolitan novels picks up when Elena and Lila, the brilliant friends who meet as children in the first book of the series, are in their thirties. Ferrante gives voice to emotions and experiences few writers articulate, and the narrator’s raw accounts of unloving sex, suppressed rage and relentless self-doubt are acute and disquieting. The Italian author is equally adept at rendering both sweeping and subtle changes of lives as they evolve and are shaped by circumstances and shifts of power and advantage among friends.

-- MAUREEN DEZELL

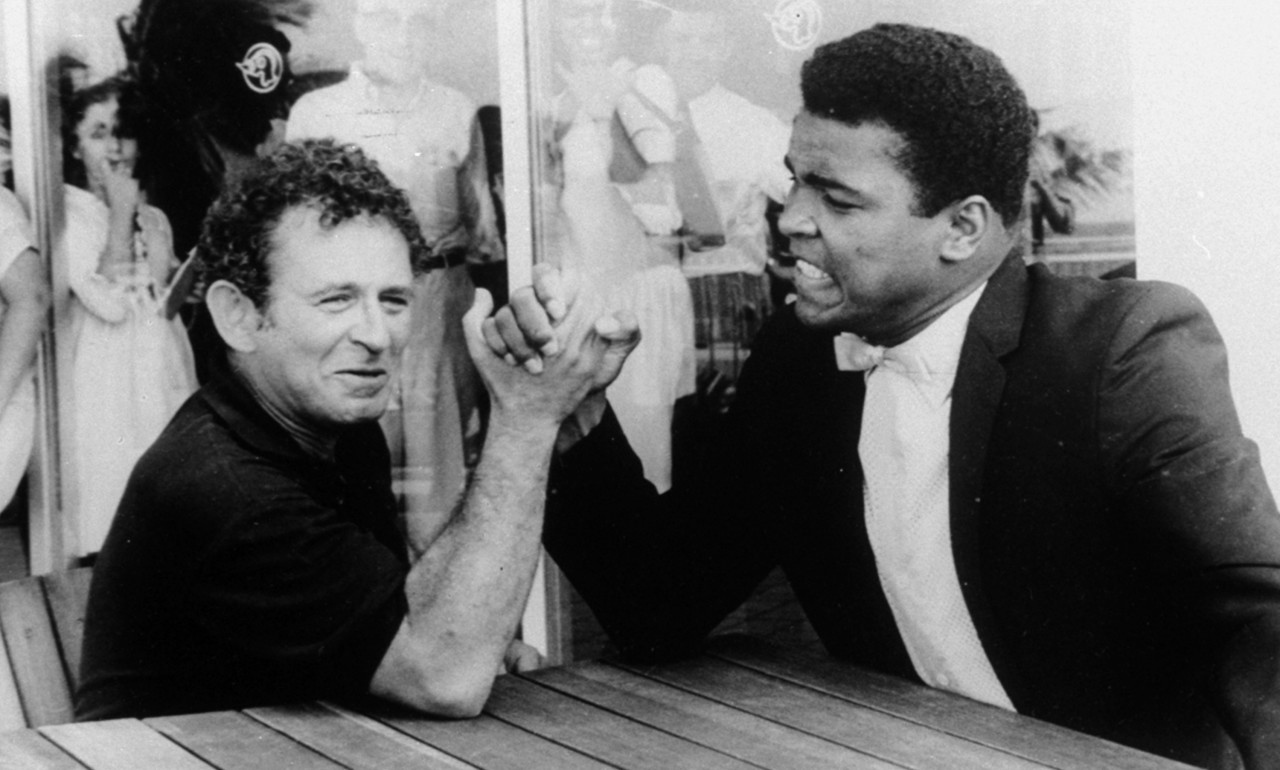

“Selected Letters of Norman Mailer” represents “the last great slab” of prose from this major American writer. And what a slab it is. Editor and Westport, Mass., resident J. Michael Lennon has culled through the lion’s share of the 45,000 letters his old friend wrote over his six decades in the public eye (and before) and come up with nearly 800 pages of intriguing dispatches to some of the most famous writers, artists, intellectuals, movie stars and politicians of the 20th century. There are also steamy letters to Mailer’s last wife, and encouraging notes to struggling writers and prisoners. The two-time Pulitzer winner was reluctant when it came to the epistolary art, but it’s hard to tell thanks to the brio and verve that shines through in even the most causal of these missives.

-- JOHN WINTERS

"A Girl Is a Half Formed Thing," the debut novel from Ireland's Eimear McBride sat in a drawer for almost a decade, impressing but unnerving major publishers. Her story of girlhood and adolescence reads like a piece of classic Modernism (by way of Beckett or Woolf) and confronts sex, family, and faith in an unblinking, simmering stream of consciousness.

-- CHARLES THAXTON

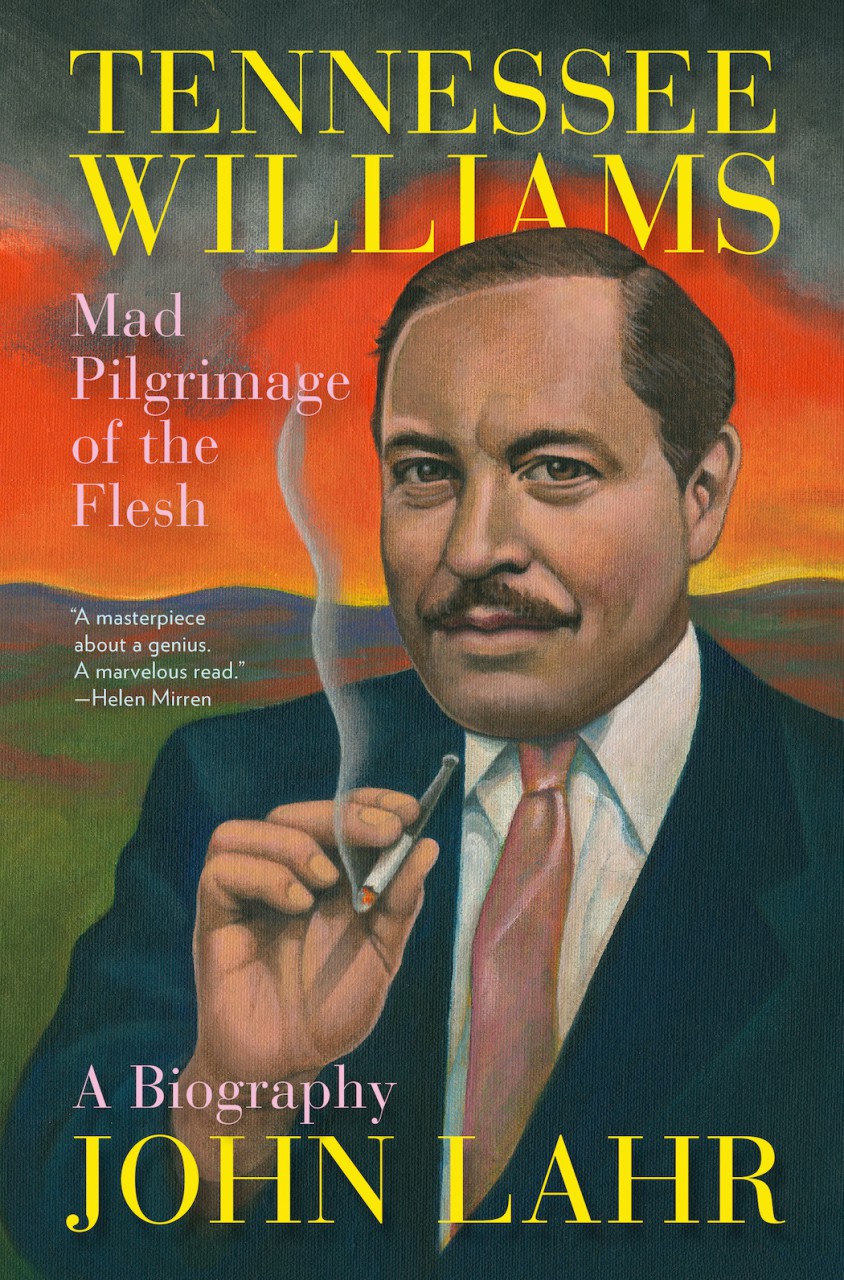

It has been more than 30 years since Tennessee Williams died of a drug overdose in New York’s Hotel Elysée. Fortunately, “New Yorker” critic and Joe Orton biographer John Lahr spent 12 of them researching and writing the definitive critical biography, “Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh,” published by W.W. Norton just this year. There have been, by Lahr’s count, more than 40 books about the author of "The Glass Menagerie," including Williams’ own disappointing “Memoirs.” We won’t need another after this riveting, juicy, insightful analysis, which actress Helen Mirren succinctly blurbs as “a masterpiece about a genius.” Bonus question: from whose vividly self-scrutinizing prose is that title taken?

-- CAROLYN CLAY

More On Books From WBUR

- On Point: Best Books of 2014

- Radio Boston: 27 Books That Make Great Holiday Gifts

- Here and Now: A Weekend Edition Editor Shares Her Picks For Best Books Of 2014

- Here and Now: Share Your Favorite Books

- ARTery's Top 2014 Choices:

- CDs in 2014: The Past, Present And Future (?) Of Classical Music

- Our 10 Favorite Rock Albums From 2014

- Local Theater In 2014: Sadists, Swindlers And Other Necessary Monsters

- Company One Goes To Town In 2014; ArtsEmerson Is A Great Host

- Forget ‘The Hobbit,’ These Are The Top 10 Films of 2014

- 11 TV Shows That Had Us Lusting For The Next Episode

- From Museums To The Streets—Boston’s Best Visual Art of 2014

- Dwarves And Dungeons, Science And Tech: The Year In Geek Culture