Advertisement

Wellesley Hosts Rarely Seen Works By The 'Father Of Modern Iranian Sculpture'

Resume

News stories involving Iran tend to focus on nuclear weapons or economic sanctions — not art.

But right now a groundbreaking retrospective featuring 175 works by Parviz Tanavoli, one of Iran's most well-known contemporary artists, is up at Wellesley College’s Davis Museum.

His works fetch record-breaking prices at auction, but “the father of modern Iranian sculpture” hasn’t had a major U.S. show since 1976.

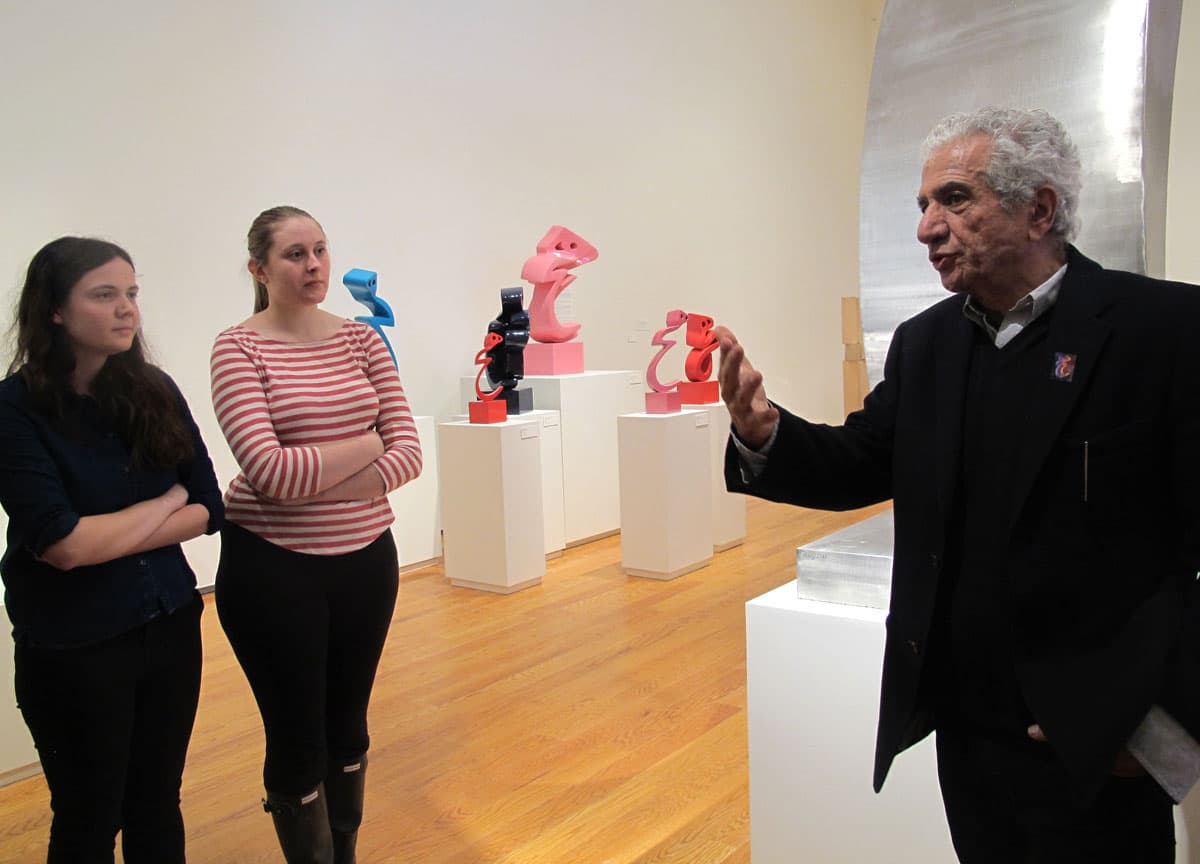

With a head of silver hair and wearing a stylish black blazer, Tanavoli, on a recent visit, looks younger than his 77 years. He speaks softly but candidly as he walks among 175 of his objects, flanked by a group of students from Wellesley. Each piece tells a bit of his personal story, but together they reveal an arc contemporary art has taken in Iran.

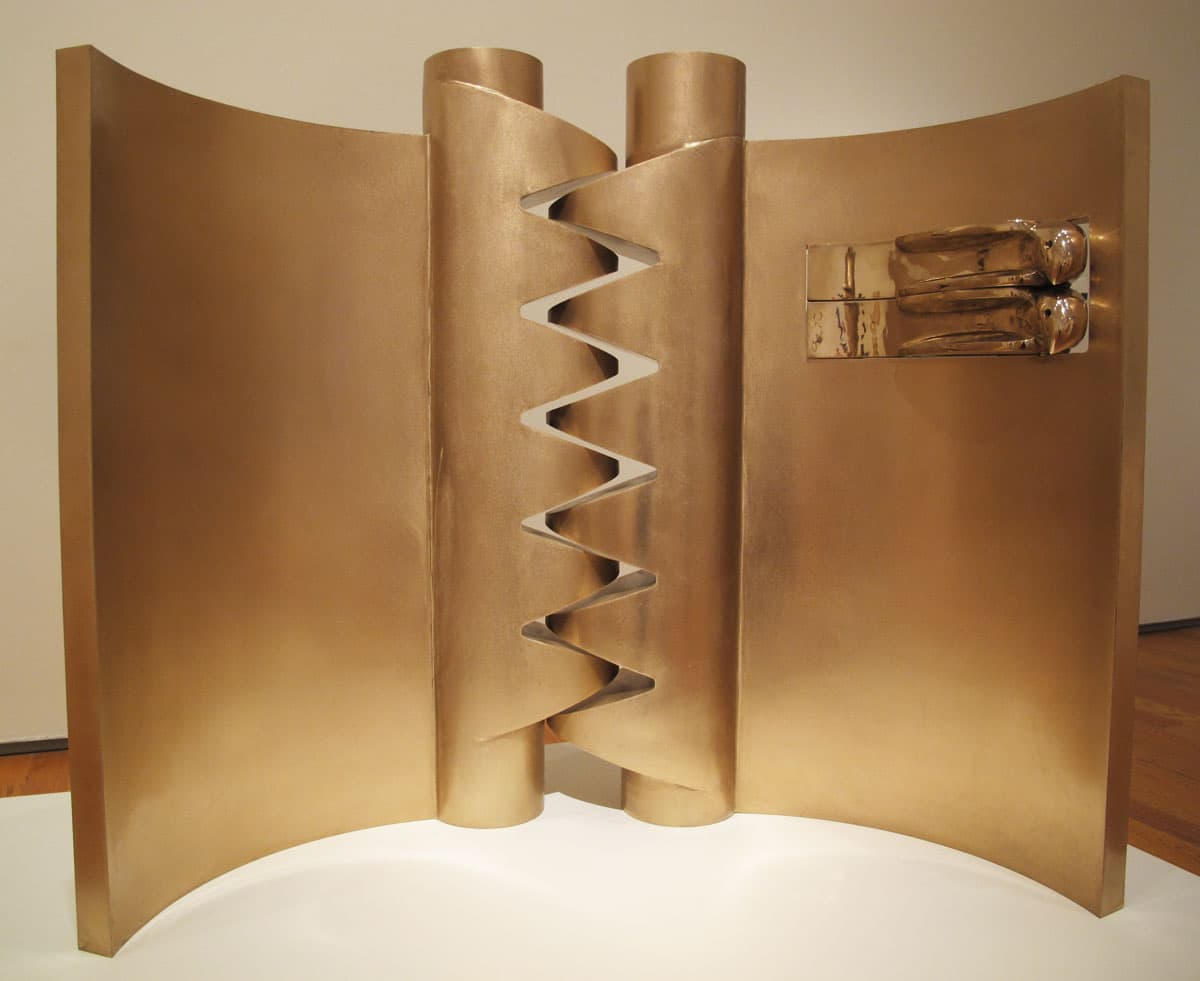

Tanavoli stops in front of his curvaceous, popular sculptures known as "Heeches." Heech is the Farsi word for “nothingness." On paper, it's a slender piece of calligraphy that's popular in Persian poetry.

“I mean, any Iranian could easily read this,” Tanavoli explains to the students. “It’s composed of three letters. H, the head is like H … then the center is like I, or double E ... this curve is like CH at the end.”

The H does indeed look like a head with two little eyes peering out. In 1964-'65 Tanavoli transformed the swooping, often-metaphorical word for "nothing" into elegant, 3-D, human-like forms that he believed Iranians could connect with.

“When I made all of this of course it was very new to them, and they didn’t realize the shape is so expressive and so graceful,” he says. “The other advantage of this word is all the meanings behind it which Iranians especially relate to because of the great poets like Rumi. They deal with this word. They question it. ‘What is Heech? Is there nothing?' ”

Tanavoli has crafted countless Heeches over the past 50 years — in ceramic, bronze, fiberglass, even neon.

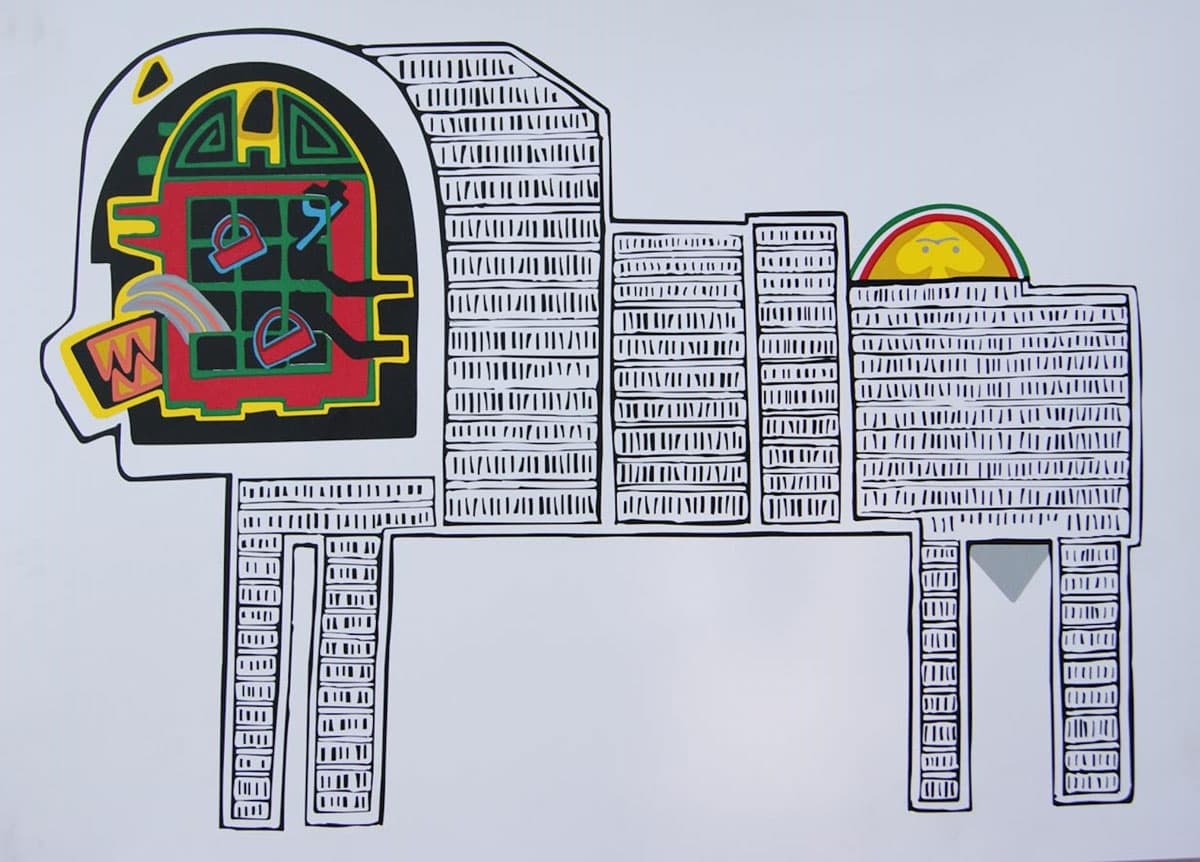

The artist’s early work actually helped revive sculpture as an artform in Iran. Tanavoli says the tradition died off after the Arabs conquered Persia in the seventh century because sculpture often represented the human body, which was seen as sinful. But after studying sculpture in Italy in the 1950s, Tanavoli returned to Tehran and opened a studio that became a buzzing space for other emerging contemporary Iranian artists. They founded a new school of pop art known as Saqqakhaneh that incorporates Iranian folk art and culture.

“It was very exciting for myself,” Tanavoli recalls. “I was young, and I thought I was doing something, and I worked very hard for it. And when I look at it today I am proud of it. ... They were good days.”

But he remembers there were challenging days, too.

“Because there weren’t that many people trained for art, and there weren’t that many followers or fans and collectors. People weren’t familiar with the modern art I was producing,” Tanavoli says.

But he did find a major supporter in the early '60s. An American collector and philanthropist named Abby Weed Grey sponsored a touring exhibition for Tanavoli and about a dozen other Iranian artists that traveled to a few U.S. cities. Grey’s foundation, which was based in Minnesota, also helped fund the construction of a fine art bronze foundry in Tehran.

While the Iranian people did eventually connect with Tavavoli’s Heeches, the artist's other works proved controversial.

In 1965 authorities shut down his gallery show in Tehran because it merged materials and imagery from the East and West. Things got more complex for Tanavoli with the revolution of 1979, the hostage crisis and the aftermath.

Ultimately he left his teaching job at Tehran University and moved his family to Toronto (for the schools, he says), but the artist still maintains his foundry/studio in Iran and lives there for part of the year.

“You can really teach a seminar in modern Iranian history through his artwork,” says Shiva Balaghi, who co-curated the Davis retrospective and is a Middle Eastern cultural historian at Brown University.

“You see the common art of the streets of Tehran represented in his work, you see Iranian folklore, ancient Persian myths,” she says. “But you also see that within Iranian society and culture there is this sense of humor that withstands regardless of the day-to-day political situation.”

But Tanavoli also delves into more brutal, confining imagery of cages, locks and jail cells. Still, Balaghi thinks Americans who visit the new show will be surprised to see how optimistic the artist's work can be.

“Because often when Iranian visual culture does make it into the mainstream it seems very dark,” she says. In Tanavoli’s art, “There is this sense of gratitude for the simple things in life — like the image of a bird flying, like the shape of a letter in the alphabet.”

Ali Khadra, of the Dubai-based contemporary art magazine Canvas, calls Tanavoli “the pride of the Middle East.” Khadra flew into Boston for a 24-hour visit just to see Tanavoli's new exhibition and to speak to the artist for 10 minutes. He calls the sculptor "a beacon of hope" for aspiring artists in the politically tense region.

“It’s like a chain reaction," Khadra begins. "When a museum is interested, an education program takes place, media talks about the artist, people at art fairs in Miami and Basel talk too, and the interest keeps growing and growing. And this is how the West will know about Middle Eastern art.”

That said, Tanavoli laments how politics have tarnished his home country's ability to share its culture.

“You know we used to be very well connected with westerners — with Americans, Europeans — but now it’s unfortunate because so much has been happening in Iran in the last 35 years. In culture, music, film…and a lot of people are not even aware of it,” he says.

But that appears to be changing. The Davis is the first of three American museums with shows featuring Iranian artists this year.

“You see the trends in the market, and you see the attention of museum directors in the West shift,” Davis Museum director and co-curator Lisa Fischman says. “And I think we have three important Iranian museum exhibitions on the East Coast, starting with Parviz’s work here. That’s a moment. It’s exciting for the artists, too.”

Tanavoli admits he’s honored to have his work act as something of a cultural ambassador.

“Iran has a long culture — millenniums of culture — but for today I think this represents Iran pretty good,” he says, smiling.

Even so, the representation of his long career that fills the Davis gallery is far from complete. Tanavoli’s famed interpretations of Persian rugs weren’t allowed in the U.S. because sanctions prohibit their import.

The Tanavoli exhibit runs from Feb. 10 to June 7 at the Davis Museum.