Advertisement

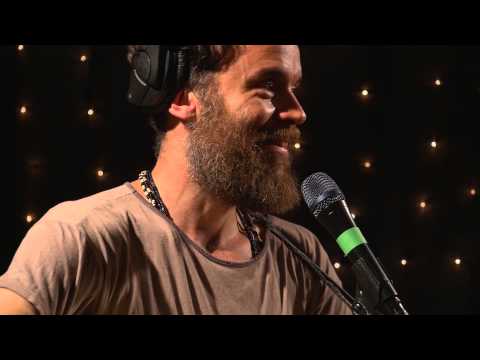

Far From Home, Rodrigo Amarante Looks Longingly Back At The Music Of His Brazil

Since moving permanently from his native Brazil to Los Angeles in 2009, the musician Rodrigo Amarante has found himself wanting to cook Brazilian food more than he ever had in the past. The salty aroma of feijoada, the ocean-tinged tang of moqueca baina. “It’s kind of obvious, but it’s interesting to see that happening,” he says. “And this record, too. I’ve written songs that are more Brazilian than what I have written before.”

“Cavalo,” which came out in the States in 2014, is Amarante’s solo debut, and likely American audiences’ first introduction to his work. But the singer-songwriter is well-known in Brazil as a member of the indie rock phenomenon Los Hermanos and the frontman of Orquestra Imperial, a retro big-band samba group. He plays Cafe 939 in Boston on April 11.

Amarante’s American crossover began with the trio Little Joy, a collaboration with the drummer Fabrizio Moretti of The Strokes and the singer Binki Shapiro. They put out a self-titled l thebum in 2008. “Little Joy” was a sweet and delicate thing, and with the samba- and indie rock-inflected “Cavalo,” Amarante continues in this gentle vein, his gaze cast lovingly, and a tad longingly, back at his homeland.

“This is a pretty universal feeling,” says Amarante. “Everybody travels and when you travel you know how it feels. You know, you feel removed from everything that reminds you of who you think you are, who you want to be, or who you don’t want to be. And then when you’re outside of that environment, then you feel slightly looser and more free to, I don’t know, present yourself differently, I guess, or to get to know yourself. I always feels like that. And there’s a saying that—I don’t even know if in English there is that saying but there probably is—that the purpose of every trip is the return. ... It’s the return, not only physically, coming back to where you started, but actually turning yourself to that place, looking to where you’re from, from afar. Returning in that sense. And that space is the environment for a new perspective.”

In many ways “Cavalo” is a departure for Amarante, even a risk. The album features songs in his native Portuguese as well as English and French, making it difficult, at least in the eyes of press agents, to market in the U.S. It possesses a spareness unlike the electric bluster of Los Hermanos or the brass effusiveness of Orquestra Imperial. And it is murkier, more at home in the twilight than “Little Joy.”

Amarante hails from Rio de Janeiro, but the family followed his father’s job around the country, an experience the singer says accounts for his own adventurousness. Although his father’s family ran a samba school (in Brazil, such schools operate more like clubs and are focused around annual performances at the carnival parades—as in the footage in the video above of family members during carnival in Brazil in the 1970s), his parents were devoted rock ‘n’ roll fans. “We never had religion in the house, but there was a big picture of John Lennon in the living room,” he says. “And if my mother had to pray, she would pray to John Lennon.”

At the age of 10, Amarante bought his first album, “The Queen Is Dead,” by The Smiths. After his sister introduced him to punk music, he asked for an electric guitar and a distortion pedal, hastening his journey towards eventual rock stardom.

It would be folly to understand “Cavalo” as the product of a purely Brazilian vernacular—its rock ancestry is clear—but you can hear Amarante reaching for his roots. The tremulous tones of classical guitar form a fragile trellis for his curling melodies, which bloom occasionally with coquettish samba inflection.

“I slowly realized what I actually wanted to do when I started writing these songs that are more slow, and emptier,” he says. “And then I realized, I mean for my own sake, that this was the most punk thing I could do. Because of my background and because of what people from where I’m from expect from me. And also what kind of music is going around now. I thought it was a lot more punk for me to play a little waltz on my guitar alone onstage, being naked there, trying to convey some sort of emotion ... because it’s a lot harder to invite rather than to invade.”

For “Cavalo,” Amarante allowed the subjects of his songs to dictate which language he wrote in. The Beatles-esque “Maná,” written for his sister, and the waltzy, wistful “O Cometa,” composed for a departed friend, had to be in Portuguese. But “The Ribbon” and “I’m Ready,” which depict a soldier’s death from two different perspectives, are written in English because they were inspired by Amarante’s exposure to American culture. “In my country, it’s not a thing,” he explains. “Billboards everywhere with men holding guns and planning for revenge, taking justice with their own hands.”

Although Amarante’s English is very good, his vocabulary is undoubtedly more limited in that language. But he says that this restriction helps him achieve a certain quality that he always aims for in his songs: a fine enough balance between specificity and obscurity that listeners may convincingly project their own experiences onto the words. Although, he adds, “Most of the time you have to be in love for that to work. Like when you’re in the back of the taxi and you’re in love and some cheesy song plays and you’re like ‘Oh my god this song is directed at me right now.’”

Amarante wrote all and played most of the parts on “Cavalo” himself. At first, he was so overwhelmed with the possibilities that he composed lush, over-the-top arrangements. Eventually he scrapped those early recordings and decided to subtract as much as he could in order to find out which sounds were really necessary. What would happen, for example, if he left out the bass? Musicians are trained to think that songs without a low end will be “weak,” he says. “I realized it has to be empty. I have to apply this idea of space that I’ve been trying to do in my lyrics—and actually musically, too, before. But now it’s just me so I can take it to an extreme that I wasn’t able to do before.”

Although minimalism reigns on “Cavalo,” Amarante’s original sense of experimentation remains. None of the songs follow the same formula. Percussion may take the form of a distant clattering or a cheerful burble, like raindrops hitting wood. Amarante sings with an intimate languor, his voice a message left on an answering machine in the dark hours of the morning. Their details may be precise, but the songs on “Cavalo” are moody, murmuring things, made up of the gossamer mental particles that gather, unbidden, in moments of repose.

On the quiet opening number, “Nada em Vão,” a saxophone enters briefly with a forceful honk before disappearing just as suddenly. You can chase that sax all the way through “Cavalo” as it reemerges and retreats, an arresting reminder of the treasures to be found when everything else is stripped away.

Correction: A previous version of this essay said Amarante wrote and played all the parts on “Cavalo” himself. He actually only wrote and played most of the parts.