Advertisement

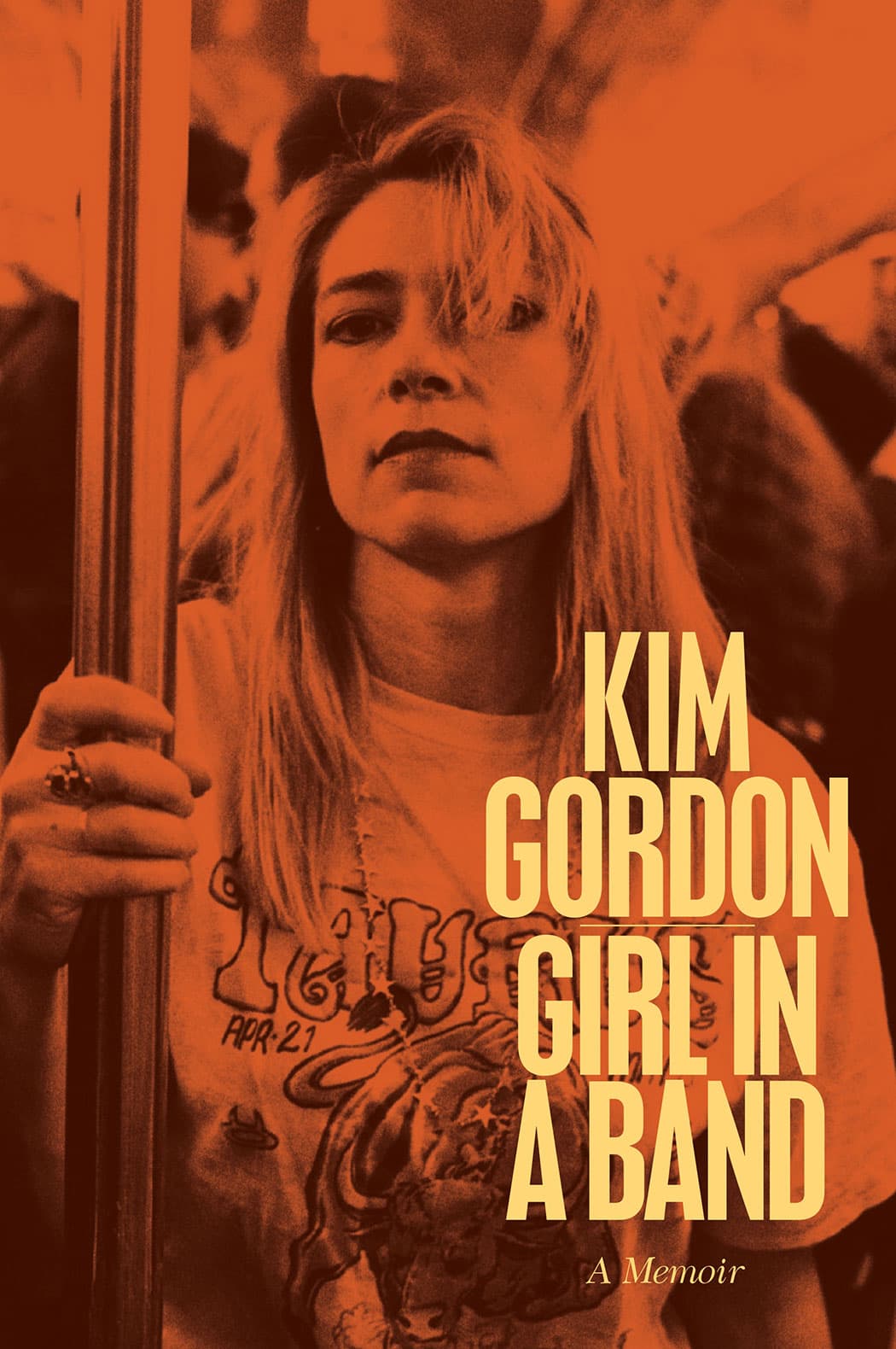

Kim Gordon Reckons With Music After Sonic Youth, Life After A Messy Divorce

“Girl in a Band” is not a story of betrayal. Nor is it a tale of a marriage gone south. It is also not a rock star’s sordid tell-all. It is, like most memoirs, mainly concerned with creating a coherent sense of self out of a lifetime’s worth of material, some of it meaningful, some of it not. It just happens to be written by a very famous artist, in the wake of a revelation that threw into question the very basis of her identity.

Kim Gordon, as anyone who picks up her book knows, was a founding member of Sonic Youth, the experimental rock phenomenon that emerged from punk’s roiling-but-receding waters in New York City in 1981. She married the band’s lead guitarist and singer, Thurston Moore, in 1984; 10 years later they had a daughter, Coco. In 2011, they announced their split, and the band’s indefinite hiatus.

The indie music community let out a collective howl in response to this news, unleashing an outpouring of angsty tweets and fraught think-pieces. Gordon and Moore, by then ensconced in a tight-knit Northampton community of hip Manhattan transplants, were idolized as much for their artistic achievements as for their coupledom; they showed a generation of rock fans that being married didn’t necessarily mean giving up the pursuit of art or forfeiting your cool factor. It was later confirmed that they divorced because Moore had been having an affair.

It’s hard to shake the sensation, opening up “Girl in a Band” (HarperCollins), of Gordon’s life careening inexorably towards that horrible episode. Gordon knows this. She begins the book with a chapter called “The End,” in which she describes Sonic Youth’s final concert, an event symbolic as much for closing a significant chapter in rock ‘n’ roll history as a 27-year marriage. “I don’t think I have ever felt so alone in my whole life,” Gordon writes.

Gordon is uninterested in the reasons for Moore’s affair, or why he was unwilling to end it. (She says that they tried couple’s counseling after she confronted him, but that he failed to end the other relationship even though he claimed to want to save the marriage.) She takes his dalliance at face value—a midlife crisis, a rock star cliché—ignoring the rather common impulse to try to understand that kind of betrayal as a symptom of larger marital problems. This leaves her to grapple with a much more difficult set of questions: Was the person she fell in love and made a life with someone different all along? And if their life together had, to some extent, been predicated on a lie, who did that make her?

“Today, when I think back on the early days of Thurston’s and my relationship, I wonder whether you can truly love, or be loved back, by someone who hides who they are,” she writes. “It’s made me question my whole life and all my other relationships. Why did I trust him, or assume I knew anything at all about him? Maybe I imposed on Thurston a dream, a fantasy.”

“Girl in a Band” is, in a sense, a reclamation of Kim Gordon. She spends the first third of the book in her childhood in Los Angeles. She writes lovingly, but not too deeply, about her parents: she depicts her father, a UCLA sociology professor, as a gentle and intelligent man, and expresses a complex identification with her mother, a stay-at-home-mom with creative impulses from whom Gordon always felt somewhat alienated. The most significant relationship in her early life is with her older brother Keller, a charismatic bully who was later diagnosed with schizophrenia. Gordon attributes her own famously enigmatic persona in large part to Keller’s abuse: “His ridiculing and button-pushing went beyond the typical sibling ragging,” she writes. “At some point I turned off entirely.” She is especially insightful about the gendered inflections of their dynamic. “Knowing I’d get mocked or teased, I would do anything not to cry, or laugh, or show any emotion at all. The biggest challenge as I saw it was to pretend I had some superhuman ability to withstand pain. Add that to the pressure girls feel anyway to please other people, to be good, and well mannered, and orderly—and I backslid even more into a world where nothing could upset or hurt me.”

The end result? An artist. “Maybe that’s why for me the page, the gallery, and the stage became the only places my emotions could be expressed and acted out comfortably,” Gordon writes.

For the most part, Gordon skims the surface of the most painful episodes in her life. Her parents’ deaths are handled in a few sensitive paragraphs, and the discovery of Moore’s affair in a handful of blunt statements. In this way Gordon is more celebrity than writer, hesitant to divulge too much. She is shy even about her relationship with her daughter, Coco, to whom the book is dedicated, although the fullness of her love emerges obliquely, sweetly, in a passage in which she describes watching Coco perform with her band: “The singer, my daughter, was fearless in her non-singer punk style that haunted me like a song I couldn’t recall.”

Where Gordon excels, as both a writer and storyteller, is in capturing the feeling of a place, the mood of a cultural moment. “L.A. in the late sixties had a desolation about it, a disquiet,” she writes. “There was a sense of apocalyptic expanse, of sidewalks and houses centipeding over mountains and going on forever, combined with a shrugging kind of anchorlessness.” She brings New York in the ‘80s to life, too, in all its filthy glory, and the feverishly experimental No Wave scene that gave rise to Sonic Youth. “Punk rock felt tongue-in-cheek, in air quotes screaming, ‘We’re playing at destroying corporate rock.’ No Wave music was, and is, more like ‘No, we’re really destroying rock.’ Its sheer freedom and blazing-ness made me think, I can do that.”

For anyone looking for salacious tales of rock ‘n’ roll excess and celebrity enmity, “Girl in a Band” is a let down. Gordon doesn’t dish a lot of dirt. But she does provide real insight into her own artistry. She describes bouncing around various art schools before landing in New York during the cusp of the gallery boom, when fine art exploded into big business. Her mentors were artists, her first foray onto the stage a performance art piece. In this way she makes a strong case for the role of avant-garde ideas in rock music. Her own approach to Sonic Youth’s sound—the dissonance, the experimentation—is driven not so much by specific musical concepts as by an interest in subverting expectations around what art can be. Gordon is also deeply invested in disrupting rock ‘n’ roll’s habitual masculinity. She shows how her interest in fashion emerged from a struggle to figure out how to present herself, a rare rock woman, onstage. (In the nineties Gordon co-founded the hip streetwear line X-Girl.) How could she own her sexuality without feeling objectified? Was it possible to cultivate cool and stay true to herself in the process?

Gordon makes clear her disdain for the media’s portrayal of women in rock, noting how often she was asked the question “What’s it like to be a girl in a band?” and later “What’s it like being a rock musician who’s also a mom?” Throughout the book she champions other women, like Kathleen Hanna of Bikini Kill and even Madonna, whose work she admires and that she views as being somewhat in line with her own. Disappointingly, however, her harshest words are reserved for other women, like Lana Del Rey, whom she views as complicit in her own objectification, and Courtney Love, whom she disparages mainly on personal grounds. If Gordon encountered much misogyny in the male-dominated world of rock ‘n’ roll, she doesn’t write about it.

That’s not to say that “Girl in a Band” is not a feminist book. It undoubtedly is. Gordon writes with great wit and insight about how her musicianship was motivated by a desire to insert herself into a uniquely male experience, one characterized by intoxicating power. In an excerpt from a tour diary, she writes, “I always fantasized what it would be like to be right under the pinnacle of energy, beneath two guys who have crossed their guitars together, two thunderfoxes in the throes of self-love and combat, that powerful form of intimacy only achieved onstage in front of other people, known as male bonding.”

In what little analysis she devotes to her relationship with Moore, Gordon makes a case for herself as a “codependent woman” and him a “narcissistic man.” “Girl in a Band” is a repudiation of codependence, a vindication of self. In many ways, that is a memoir’s inherent project: to seize control of your own story, to answer the question “Who am I?” But for Gordon it is especially vital, given how thoroughly her sense of self was tied up with someone else, and how utterly it all came undone. There is perhaps no better way to assert one’s subjectivity than to embark on a search for meaning. For Gordon, the search always returns her to art.