Advertisement

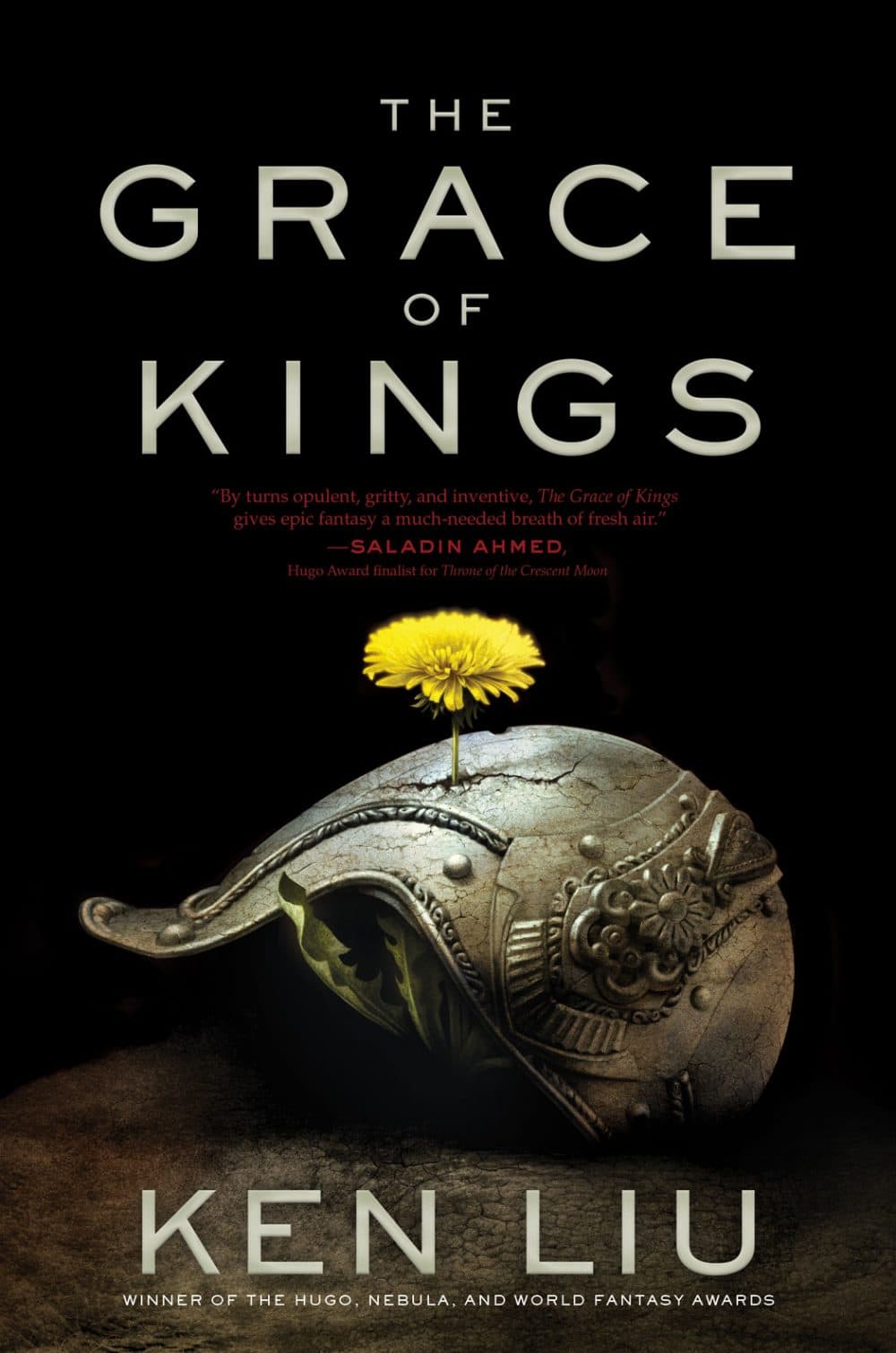

Ken Liu’s ‘Grace Of Kings’ Is An Epic Steampunk Reimagining Of Chinese History

Some years back, Ken Liu saw a call for stories about wizards from a fantasy fiction publication. The Stoughton author dreamed up “The Paper Menagerie,” a heartbreaking tale about the origami creatures that a mail-order-bride mother magically makes come to life for her son, about the boy’s disdain for her, and his eventual regret of treating his mother so badly.

That first fantasy magazine rejected it. But when the short story was published in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction in 2011, it swept the Hugo, Nebula and World Fantasy awards, the top science-fiction and fantasy writing prizes, and announced the arrival of a major new writing talent. (It will be reprinted in his collection “The Paper Menagerie and Other Stories,” due out from Saga Press, an imprint of Simon & Schuster,” in November.)

Liu—who is interviewed below—spent his early years in Lanzhou, China, then moved with his family to California when he was 11. He says he attended high school in Connecticut, then Harvard University, before working as a programmer at Microsoft in Seattle and a Cambridge startup. He says he returned to Harvard for law school, followed by seven years practicing corporate law. He says he’s now a litigation consultant in Boston, a job that has allowed him to pursue writing fiction diligently for some five years.

Last November, his English translation of “The Three-Body Problem” by Liu Cixin (“the best-selling Chinese science-fiction author in decades,” according to The New York Times) was called “insanely riveting” by Annalee Newitz, editor of the eminent sci-fi blog io9.

Saga Press recently published “The Grace of Kings,” Liu's epic reimagining of the founding of China’s Han Dynasty a millennia ago and the great tales it has inspired. Liu says he used to rush home at lunchtime to listen with his grandmother to a version of the history, “The Chu-Han Contention,” told on the radio.

The first novel of a planned trilogy, “The Grace of Kings” is populated with swashbuckling rogues, wily inventors and steadfast heroes. Plus Liu adds steampunk war zeppelins and a gender-swapped general. It reads like folklore, straddling Chinese and Western traditions. At the heart of the story are two men, who begin as friends, but become bitter enemies. Mata Zyndu (based on Xiang Yu) is a noble-born, larger-than-life warrior driven by honor, which fuels both his successes and failures. Kuni Garu (inspired by Liu Bang, who became the Emperor Gaozu) is a shiftless, but wily ne'er-do-well whose intellectual flexibility and appeal to the people helps him navigate his way to the top.

Below, Liu speaks (in lightly edited form) about “The Grace of Kings," the "Silk Punk" world he’s created, and his efforts to reimagine traditional epic fantasy tales as well as critique them.

• Ken Liu: “I describe [‘The Grace of Kings’] myself as ‘Silk Punk.’ The marketing term does double duty. One is a reference to the fact that I’ve created a very steampunk-like world, but the technology vocabulary is very different from steampunk in that it’s reliant on materials of historical importance to East Asia like bamboo, paper, things like that. And on materials that are important to seafaring cultures of the Pacific, like coconuts, feathers, fish scales, things like that. At the same time, there’s a biomechanics quality to a lot of the machines and inventions. The airships, they regulate their buoyancy using these gasbags that work like swim bladders in fish, which is very different from the way zeppelins in our world work. They propel themselves by these huge oars. So even the way they move is very different. They have this jellyfish-like quality to it.”

• “The other reason it’s called ‘Silk Punk’ is because I want to take the idea of punk seriously. This is an epic fantasy that isn’t about a return to the past, about the golden age. Rather it’s about revolutions, continuous revolutions.”

• “I wanted to create a new world that draws inspiration clearly from East Asia, but isn’t China. That’s the only way I can let people see the story anew. I’m very interested in foundational narratives. Foundational narratives in the West are things like the ‘Iliad’ and the ‘Odyssey,’ ‘Beowulf,’ ‘Paradise Lost.’ These are very important epic stories which become the foundation on which new works comment and elaborate and are in conversation with. In the Chinese literary tradition, the same role is played by stories like ‘Romance of the Three Kingdoms’ or the ‘Chu-Han Contention,’ which is a source for ‘The Grace of Kings.’ But I didn’t want to retell a story, rather I wanted to reimagine this very old important foundation narrative of the Chinese literary tradition in a brand new literary framework that I constructed myself out of my status as inheritor of both Western and Chinese literary traditions.”

• “There’s this long history of colonialism and the colonial gaze when applied to matters related to China. So a lot of conceptions about China in literary representations in the West are things you can’t even fight against because they’ve been there so long that they’ve become part of the Western imagination of China. For example, the idea that China is full of despots and that for thousands of years people didn’t really do anything about that, it’s a passive population of people who are sophisticated and cultured, but ultimately lacking courage to challenge the status of their oppression. That tends to be a very Western view of Chinese culture. It’s wrong because it’s not true. It’s a very Western way of viewing a population that they don’t understand and want to fit into their worldview. It justifies colonialism and colonial invasion. The book is an attempt to get away from that.”

• “A lot of epic fantasy—not necessarily contemporary ones, but certainly older epic fantasies—follow this model of the world is stable and then it becomes chaotic because something has disrupted the stability of the order and the hero’s job is to restore order to that world and make things to go back to the status quo, to go back to that golden age. That’s really what ‘Lord of the Rings’ is about. I tend to not really like that kind of story because I think a lot of times fantasy has the potential to represent revolutions and change and we don’t use it to do that. I chose to use this bigger story to explore that theme. Mata represents the return a golden age. He is the noble. He believes that the way the world used to be before all this stuff happened was the better world. He represents in some ways a very common criticism of the first emperor, the way he disrupted everything.”

• “In every revolution, there are winners and losers. Every dystopia is a utopia for somebody else. It just depends where you are. Are you in the class that benefits or are you in the class that’s not? Mata’s view is sort of like, ‘It was a golden age because my family was awesome and I had this destiny and that is the way it ought it be. Everybody should be in their place and we have the great chain of being and that is good.’ And Kuni’s view is, ‘Look, I didn’t live during that age, but things are different now. I want to make the best life for myself and people I love. I want to help people. I think everybody deserves a better life than they’ve got. It’s a matter of compromises and balances.’ So the first book is just really the start of the arc. The trilogy as a whole is about continuous revolutions and change.”

• “This is a story very much concerned about all the ways in which every system, however idealistic it may be, tends to have winners and losers and oppressors and the oppressed. The cycle of trying to reach more justice is one that can never end. There is no golden age because we’re always trying to perfect ourselves and yearning towards a future that’s better.”

• “I’m trying to challenge both the source material as well as the framework that I’m putting it into. Because one tendency for people to say when they do a reimaging of a historical story is ‘This is history, this is the way it was, I’m just going to follow it.’ But I think that’s just not as interesting. If I’m going to stick giant scale whales in there and airships, then why not do something more to think about what it means to have revolutions. How would you try to implement a society in which those who have no power are given more power? What does that mean? Is that really something that can be done? I feel like a lot of epic fantasy is so darn focused on monarchial systems and the idea of honor and kingship, and ‘The Grace of Kings’ is very much about that, but at the same time I think we can write great epic fantasy about the idea of democracy and democratic ideals. In fact, there’s a lot of yearnings for that kind of more participatory system of government in classical Chinese thought. They’re often not understood or even known about in the West.”

• “I was not trying to write some sort of serious meditation on war and peace. ‘The Grace of Kings’ is meant to be a fun book. It’s meant to be an epic fantasy. You read it and you’re like, ‘Cool, there are these silk-bamboo airships, there are these submarines, there are people jumping out of airships and diving, and people with huge swords, and this kickass woman general who wins by guile.’ It’s meant be fun. There’s a lot of intrigue and a lot of historicity and a lot of very serious stuff when I was writing it. But none of that really matters if the story isn’t fun.”