Advertisement

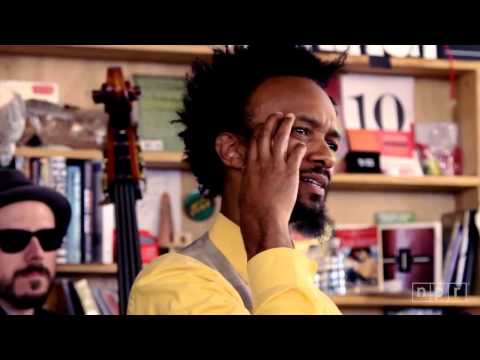

Tiny Desk Contest Winner Fantastic Negrito Revives Himself With The Blues

Fantastic Negrito, the winner of NPR’s inaugural Tiny Desk Concert Contest, seemed to emerge out of nowhere. This was partly by design—one of the requirements of the contest was that artists be unsigned, so it is not exactly surprising that the champion was a relative unknown. But the Oakland, California, musician’s video submission of his original song “Lost in a Crowd,” which was filmed live in a ratty-looking freight elevator, depicts a performer with the voice and bearing of someone far more seasoned than the ordinary breakout star. With his tousled puff of hair and slick three-piece suit, crammed into a dingy cube with thee other musicians and a standup bass, Fantastic Negrito at once seems to absorb and transcend his lowly surroundings. His voice is raspy and wounded and euphoric, all at the same time.

Fantastic Negrito, whose given name is Xavier Dphrepaulezz, says that the directness of his delivery comes straight from the blues. “I can really relate to just hearing Skip James sitting there with his guitar and his voice. Nothing else. No frills. As I call it, the shortest distance travelled. And that’s what I try to take away in the studio. Like when I’m in the studio, that’s my influence; it’s like, ‘How do I get there [with] the shortest distance travelled, production-wise?’ That’s what I believe Fantastic Negrito is. And that’s what I strive for. And that southern Delta music has become my greatest influence.”

Dphrepaulezz performs at Brighton Music Hall in Allston on July 27, three days after the release of a deluxe edition of Fantastic Negrito’s self-titled EP. The EP contains two additional tracks, including the first studio version of “Lost in a Crowd.” The songs on “Fantastic Negrito” are slithering, energetic and utterly confident.

But that sound was a long time coming. “I think it just took living,” says Dphrepaulezz. “I’m one of these people, I had to go through all these traumatic experiences.”

Dphrepaulezz grew up in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, the middle kid in a sprawling, devoutly Muslim family. His was one of the only African-American families in the area. “When I was born my mother said all the nurses wanted to come see the colored baby,” says Dphrepaulezz. As a child, he remembers feeling like an outsider and sometimes being the target of racist slurs.

When Dphrepaulezz was a pre-teen, the family moved to Oakland. It was the first time the young man had lived in a city, let alone been surrounded by so many other people of color. “I felt like I had been starved, and finally I could eat,” he says. “And I felt like I was home.”

Dphrepaulezz says he started running with a rough crowd, fighting in school, and dealing drugs. Eventually he landed on the street. It was the ‘80s in Oakland, and hip-hop was happening, along with the crack epidemic. “What happened there was music, art, culture, people, violence, drug dealing—I mean you name it,” says Dphrepaulezz. “It was all happening and I wanted to be a part of it. I smelled something in the air and I had to be a part of it.”

Eventually, Dphrepaulezz says, he was sent to a reform school and ended up in foster care. He credits the woman who took him in as a teenager for saving his life. “Even when I got there, I thought about robbing the house,” he recalls. “But then she showed me so much love that I just changed as a person. She let me dress weird and be a weirdo. ... She directed me towards music and she saved my life.”

A new track on the “Lost in a Crowd” EP, “She Don’t Cry No More,” is dedicated to that surrogate mother. The song is not a lament so much as a muscular dirge propelled by big, deliberate backbeats. Dphrepaulezz’s voice is sorrowful but not wallowing, animated by the certainty, the necessity, of death: “Now the rain falls down on me/ She don’t cry/ She don’t cry/ She don’t cry no more.”

Dphrepaulezz says he caught the bug to perform in high school when he won a school talent show as a dancer. After reading that Prince was self-taught, he decided to teach himself to play music. He was still in his early 20s when he was signed to Interscope and released an album, “The X Factor,” as Xavier in 1995. The record was a commercial flop, and Dphrepaulezz languished on the label for five years. “Everybody agreed I had all this talent, but I didn’t know what to make of it,” he says. You can hear that uncertainty in “Saturday Song,” a bland mish-mash of pop and R&B with a young Dphrepaulezz eschewing bluesy hoarseness for a Prince-esque falsetto. A trip into Xavier’s YouTube archives finds salacious music videos alongside earnest political statements and an artist unsure of what image he wants to project—Is he a Don Juan? A hippie? A bad-ass?

About five years after “The X Factor,” Dphrepaulezz says, a near-fatal car accident put him in a coma for several weeks and hastened the end of his Interscope deal. He suffered permanent damage to his hands and arms, making playing the piano and guitar difficult. Eventually, he says, he became a farmer, raising chickens and growing weed. Along the way, he pretty much gave up music entirely.

But one day, when he was trying to quiet his fussy young son, Dphrepaulezz started noodling around on an old guitar.

“I picked it up and I played an open G chord, and I remember the look on [my son’s] face was so amazing and so powerful,” he says. “It scared the shit out of me and excited me at the same time. I almost wanted to ask him, what are you doing? What are you doing responding like this to music? I think that began a slow walk back into it. ... I just couldn’t believe how much that kid loved that open G and I thought, what is he hearing that I’m not hearing? There was such a purity and innocence in that expression.”

A couple of years ago, Dphrepaulezz started busking on the streets of Oakland. In this new incarnation, he found himself fascinated with the blues—Robert Johnson, Lead Belly, Son House. When he started writing songs again, they were brooding, but simple and strong.

“I became Fantastic Negrito, and I felt like there was a rawness and an honesty in that music that I could relate to. That I was ready, finally, in my life to be that honest with myself. I couldn’t tell this story years ago.”

Dphrepaulezz says that the moniker “Fantastic Negrito” is “a way to celebrate and give attention to what I call black roots music.” “Negrito” is Spanish for “little black one.” And Dphrepaulezz is right—there is something playful in that diminutive construction. But there is something unsettling, too; after all, “negrito” brings to mind a far more pejorative term. That complexity—weight tempered by impishness, a painful history transformed into music—is what comes through most powerfully in Dphrepaulezz’s performances. What’s more, he manages to do it intimately, unswervingly, by the shortest distance travelled.