Advertisement

'The Look Of Silence' Turns A Compassionate Eye To Victims Of An Indonesian Massacre

"The Look of Silence," the new movie from filmmaker Joshua Oppenheimer, delves into the same period of bloody unrest that marred Indonesia in the mid-1960s that his highly lauded 2012 documentary, "The Act of Killing" plumbed, but from an entirely different angle.

"Killing," which was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Documentary, allowed the sadistic perpetrators behind the mass executions to put their own spin on their unconscionable deeds, but not without Oppenheimer's subtle, yet biting illumination of the heinous nature of their transgressions and the unrighteous impunity they received from a capitulating government looking to bury the past and move on. "Silence," by stark contrast, is the salving counter flow to "Killing," a cathartic podium for the survivors and family of the victims who live with daily reminders of the ghastly past and the constant duress of a reoccurrence.

How Oppenheimer arrived at such a place of riveting paradox, ghostly horrors and egregious complacency is almost as compelling a story as the ones told in his films and the tumultuous history of the Islamic archipelago. As a college graduate in his 20s, Oppenheimer signed on with the International Union of Food and Agricultural Workers to make a documentary somewhere in a developing nation to highlight workers' rights violations on plantations and mass producing farms.

"It could have been anywhere," the filmmaker recalls, "you'd think South America or Africa, but I went to Indonesia." While working on the documentary Oppenheimer found it difficult to get the workers, who were working under what the director calls "slave-like conditions," to open up. "There were these thugs there that kept silencing them. The workers were really fearful and when someone finally said something they told me about 1965."

Oppenheimer who studied filmmaking at Harvard and resides in Copenhagen, admittedly (at the time) didn't know the full extent of the atrocities that lay in Indonesia's bloody past. Back in the mid-1940s, the Dutch colony won its independence from the Netherlands after the island was released by the Japanese at the end of the Second World War. Its first president, Sukarno, a galvanizing hand in the quest for independence, would lead the country for nearly 20 years until the September 30th Movement, an attempted coup allegedly initiated by the Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI) — there has been speculation of a plot from within the military — that would send the island nation into turmoil — something that the gripping historical drama, "The Year of Living Dangerously" (1982), starring Mel Gibson and Sigourney Weaver, captured quite well.

The overthrow never took root and the backlash from the military and Islamists was swift and extreme. They reestablished the government as the "New Order" and launched a systematic extermination of all communists, known sympathizers and transplanted Chinese. To do so, street militias were formed with loose ties to the military which enabled megalomaniacs wielding sharply honed machetes free reign to mete out murderous condemnation without any due process. The death toll from those two violent years has been estimated at around 500,000, Oppenheimer believes it to be closer to one million.

Moved by the stories he had heard from the plantation workers (whose no-to-low cost labor produced rubber for American conglomerates like Goodyear), Oppenheimer returned to Indonesia in the early 2000s to see if he could get some of the perpetrators behind that horrific street justice — many of whom were regarded as heroes — to tell their side of the macabre purge.

Oppenheimer knew he had to be strategic and careful in his handling of such a sensitive and flammable subject, but as he began to make contact, what he found shocked him. "Some of the perpetrators took me down to Snake River and showed me where they killed 10,500 people," he says of the infamous killing ground. "I didn’t want to commingle them at first because they might tell the other to be quiet, but as I eventually brought them together they became more boastful and gained a greater sense of impunity."

The air of unbridled braggadocio overwhelmed Oppenheimer. "I felt like I had walked into Nazi Germany," he says of his impression, "40 years later, if the Nazis had won and were still in power. I also knew at that time too I would make two stories, one about the perpetrators and their delusions and fantasies, and the other about the victims having to live with their oppressors and lingering fear."

To get at the seemingly irrational rational behind the amoral slaughter in "Killing" Oppenheimer gave ordained butcherers like Anwar Congo video cameras to stage "recollections" of their deeds. The garish offerings featured riffs on old Hollywood movies, nightmarish beheadings and cross-dressing killers adorned with leis. The ingenious angle and absurd and shocking footage in its raw state drew support from Academy Award filmmaker and Cantabridgian, Errol Morris and later, Werner Herzog. Both served as executive producers on the films.

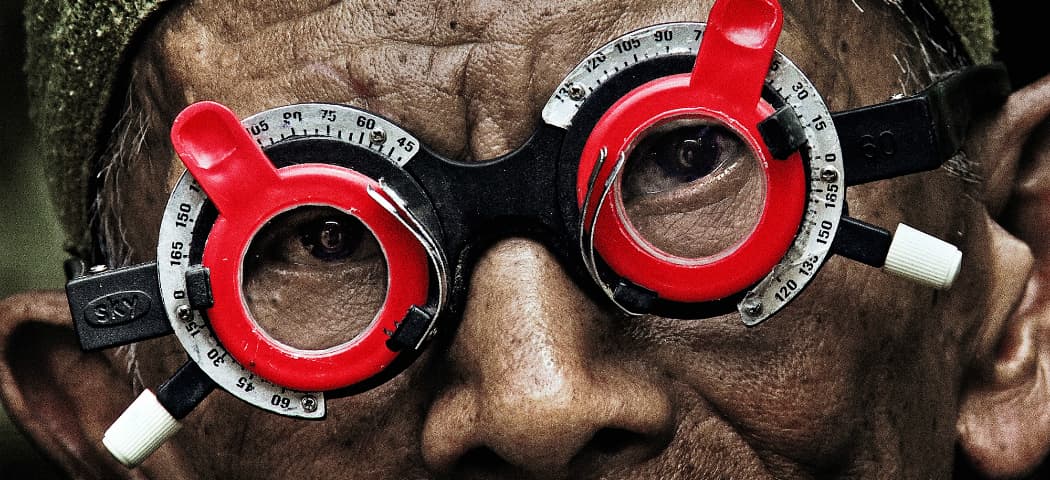

In shooting "The Look of Silence" a camera was provided to only one subject, a quiet reflective optometrist named Adi, who's brother Ramli was brutally killed by the militia. The bizarre and telling twist comes in the fact that Adi often services many of the men culpable in his brother's demise. Due to the huge age gap in his expansive family Adi however, was not even born when Ramli perished.

In the one scene he does shoot that is in "Silence," Adi's 100-year-old father crawls through his rustic abode in a fit of confusion because he's forgotten everything, not that his son has gone missing, but their familial history and the country's heinous past. It's a tragic and metaphoric moment because while he's attuned to the pain and absence, he is unable to register the injustice that has caused him such anguish over five decades.

By comparison "The Look of Silence" is a much more somber and telling work, and while it lacks "Killing's" lurid enigmatic allure, it's no less dark and registers wholly, one hundred times, more human. Adi's quest to confront his brother's executioners (who, in a disturbing scene reenact the slaying, laughing about lopping off Ramli's testicles and with amusement note that difficulty and the drawn-out process of killing a struggling victim) becomes universal.

Justice is not possible or the aim, and the fact that revenge is not the goal, "Silence" takes on a sheen akin to the actions of the victims of the recent and needless massacre of the nine blacks at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in South Carolina; they forgave, and in forgiving, they took the light from the shooter and put a human face on their beloved. Adi in questioning the past and living among the people who took the life of his brother with comported dignity, ultimately transcends, even in the face of veiled threats ("You're talking politics," an official chides and hangs out the notion that the past might repeat itself), and Oppenheimer, in his quiet, observant, yet scrutinizing manner, champions Adli, not out of forceful agenda, but out of truth and heart.

"Killing" didn't quite put the wave of national and international pressure on the government of Indonesia for accountability and reparations the way Oppenheimer might have liked, but he has received numerous death threats. Perhaps with the more human voice of "The Look of Silence," greater reflection will come.

Oppenheimer will be in attendance at the 7 p.m. showing at the Kendall Square Cinema on Saturday, Aug. 1 and will do a post screening Q&A with Errol Morris.

Tom Meek is a writer living in Cambridge, Mass. His reviews, essays, short stories and articles have appeared in The Boston Phoenix, Paste Magazine, The Rumpus, Thieves Jargon, Charleston City Paper and SLAB literary journal. Tom is also a member of the Boston Society of Film Critics and rides his bike everywhere. You can follow Tom on Twitter at @TBMeek3 and read more at TBMeek3.wordpress.com.