Advertisement

An Interview With Joyce Carol Oates: The Master Of Fiction Talks Memoir

Four years ago, novelist Joyce Carol Oates published “A Widow’s Story,” a devastating and heart-wrenching memoir about the sudden death of her husband Raymond Smith and its aftermath.

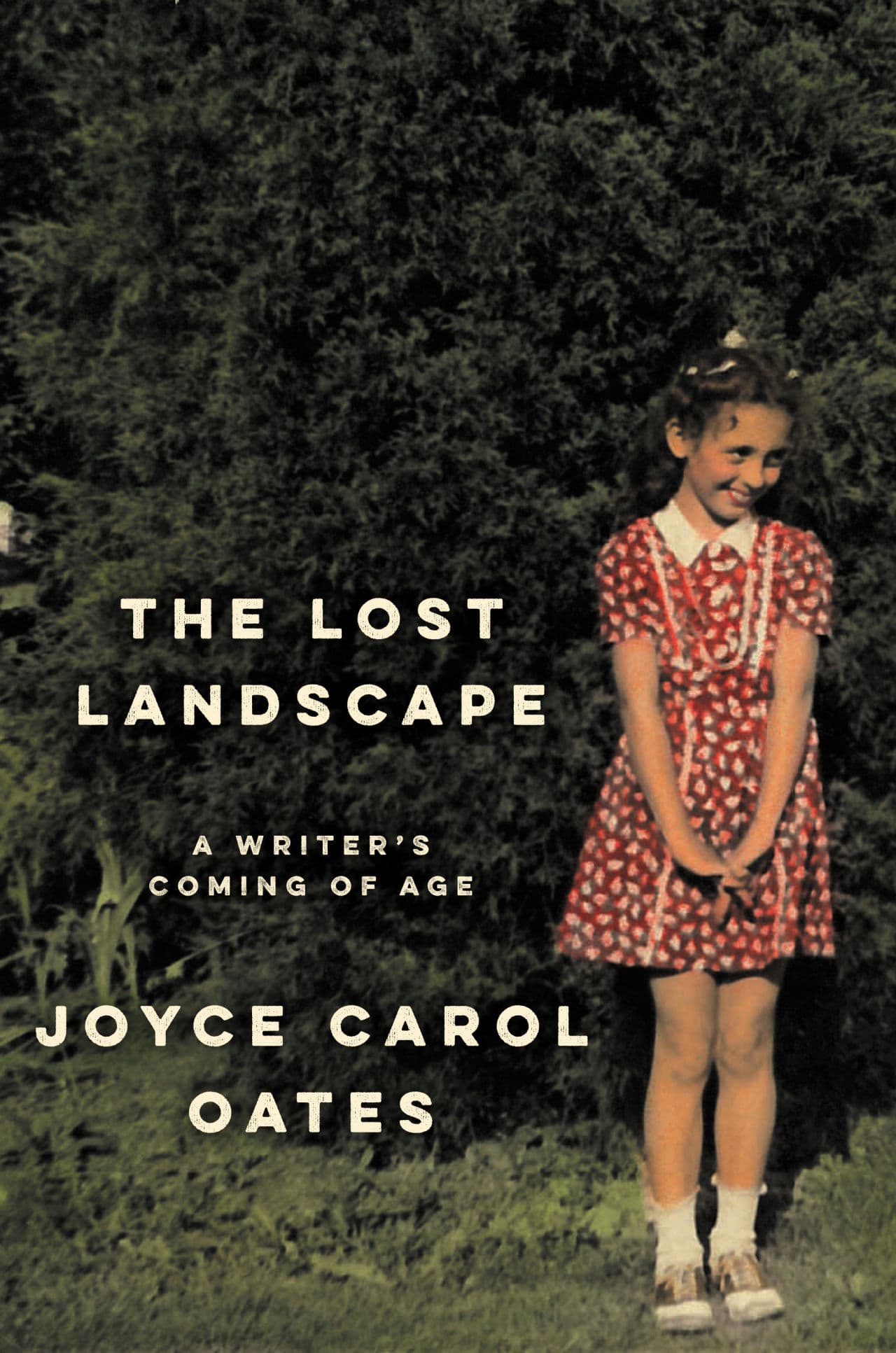

Last month came another memoir, “The Lost Landscape: A Writer’s Coming of Age,” which concerns what the title suggests, starting with her childhood in upstate New York — shy, feeling like an outsider — and going through the years spent in academia in Detroit and Princeton. And in the process, becoming a writer: She began writing at 14 and published her first novel at 26.

Oates doesn’t portray herself as the most social of creatures. She’s fine with that. “Aloneness,” Oates writes, “makes of us something so much more than we are in the midst of others whose claim is that they know us.”

“The Lost Landscape” is about the events that shaped her, but it’s not all about her. There’s a severely autistic younger sister, a friend who commits suicide, a girl put into foster care after her drunken father burns down the house. There are some sweet memories, too, from the emotional support she got from her parents to the pleasure that came from “bad” childhood foods, like Heinz pork and beans, canned pears and Hostess CupCakes with “cream” filling.

(Oates reads and signs books at First Parish Church in Cambridge on Monday, Oct. 19 at 7 p.m.)

I’ve been reading Oates for years, and have barely scratched the surface of her work. She’s written countless essays and short stories, 14 nonfiction books and 53 novels.

The title of last year’s short story collection, “Lovely, Dark, Deep,” (nominated for a 2015 Pulitzer Prize) describes much of Oates’ work. Now 77, Oates rivals Stephen King in terms of being one of America’s most prolific writers. And she can equal him when it comes to squeamish horror, albeit writing what might be called “literary horror,” as well. Her 2013 novel, ”Daddy Love” — about the abduction of a young boy who’s raised (and tortured) by a part-time preacher — is positively gut-wrenching.

In “The Lost Landscape,” Oates writes about her private life as being something out of Laura Ashley, yet, of course, she deals with some very violent, disturbing images in fiction. I asked about the process that lets her go down those dark paths. How did she get into those places, those zones where she created descriptive scenarios that can range from discomforting and queasy to out-and-out horrifying?

“I tend to be drawn to stories in which individuals who might be considered weak or disadvantaged manage to triumph, in the end,” she says. “Perhaps not completely, but to a degree. The story engages me in that it defies expectations.”

In the press notes for “The Lost Landscape,” Oates says it is “not meant to be a complete memoir of my life — not even my life as a writer.” Her focus is on what she calls the “landscape of our earliest, and most essential lives.”

In a recent email interview where, as you’ll see, Oates goes into considerable detail, I asked if writing “The Lost Landscape” was in any way a soul-cleansing experience. Her one-word answer: “No.”

Jim Sullivan: Does writing a memoir require a different kind of bravery or boldness than writing a novel?

Joyce Carol Oates: I don’t know that “boldness” is an element in writing — it is difficult to isolate qualities that go into creating any sort of art. The origin is in the imagination, and what emerges coalesces into a kind of “story” — or “narrative.” There is an essential integrity to the material which the writer/artist tries to express, as honestly as possible. I am not really aware of being a “bold” writer. … If there is a story that requires being told fully, then it may seem “bold” to a reader, while to the writer it is something other. (Perhaps this is why many writers, including me, are often surprised at the responses their work draws, which they could not have anticipated.)

Why has the memoir form become so popular?

The first frankly confessional writing in American literature seems to have been F. Scott Fitzgerald’s painfully candid “The Crack-Up.” This is memoir in the guise of self-abnegation and exposure. Fitzgerald was a Catholic, & perhaps it is a Catholic gesture of “confession” — in this case openly, lavishly. Then, in the late 1950s & 1960s American poetry exploded — the Confessional Poets (Lowell, Berryman, Sexton, Plath, Snodgrass) & the Beatniks (Ginsberg, Corso). More formal prose memoirs by Frank Conroy, Tobias Wolff, James Salter, Frank Conroy, Mary Karr et al combine some of the elements of “confession” with elements of autobiography. The memoir is popular because it is usually very accessible to readers, without the complexities of literary post-Modernist fiction; its meaning is made explicit.

“A Widow’s Story” was a collection of journal outpourings written while in the throes of four months of abject grief. This book is more measured and thought-out, and, obviously, stretched out over a long period of time and not motivated by a single event. Did writing “A Widow’s Story” in a sense open up the memoir door more for you?

Most chapters of “The Lost Landscape” had already been written as magazine and anthology pieces when I undertook to compose “A Widow’s Story.” Some date back for years, others are more recent. I had actually been working on the manuscript titled “The Lost Landscape” for perhaps fifteen years, always with the first, single-paragraph chapter at the start, “We Begin … ” I would reread this, and feel the urge to write, but did not complete the memoir until a year or so ago.

You wrote that you’d written “quasi-memoirs” before (“I’ll Take You There”) and there’s “The Journal of Joyce Carol Oates, 1973-1982,” but with “A Widow’s Walk” you dove in head-first. I’m presuming that was almost a labor of necessity (and love, for your late husband). When all is said and done, what did you gain from writing that book?

What did I “gain”? I’m not sure how to answer this. … It was an account of several months that seemed, at the time, unaccountable, inexplicable in language. The experience of grief, the unraveling of a personality, some hope of commemorating my late husband Ray.

In “The Lost Landscape: A Writer’s Coming of Age” you look back on your life, growing up, becoming a writer and all that entailed. You don’t deal much with Ray, explaining this book is not where you’re dealing with his death (done that).

You also reflect upon "A Widow’s Tale’s" "quixotic" nature: "A memoir of a death is an attempt to commemorate the living being, who has passed into ‘death.’ But it is not an attempt, usually, that succeeds in evoking anything of the fleeting, thrilling, elusive, essentially unsayable impressions that pass between individuals, rarely just words, but rather mannerisms — facial, expressive, part-conscious. There is the mystery of touch, touching. Impossible to convey."

By that definition any attempt is, to some degree, a failure. I’m thinking the goal is to get the closest you can to what you perceive the truth to be.

Yes, the elements of “fiction” that help us experience an event, not just read about it, that evoke rather than summarize, are the desired goal in this sort of memoir.

You say that Ray did not read your novels and you write he “knew so little of my writing.” That, of course, is the only way most of us know you. Did you wish he did read your novels, by which he would know you better or was there a comfort zone in him not doing so?

I think this was something that just happened. I did — probably — feel more comfortable without Ray reading my work; then in time, as he had much reading to do as an editor, it did not seem feasible that he should read more. … Ray was an excellent, natural “editor” & could not read a manuscript without feeling required to “edit” — so perhaps I did not want to burden him further. As the editor of Ontario Review, Ray was almost literally always reading/working on something to do with the Review or the press.

In writing “The Lost Landscape,” is this an attempt to let the rest of us in on the Joyce Carol Oates we only know through novels and essays?

Again, very hard to answer. I don’t “see” myself very clearly & feel quite transparent.

You’re lifting the veil further, becoming more emotionally naked. How did you feel about that?

? I don’t have strong feelings, ordinarily.

After Ray’s death, you met Charles Gross at a dinner party and were married in 2009. Does he, like Ray, not read your novels? Have you changed your approach toward life or writing or romance since Ray’s death? And is Charles fine with you revealing the many details of your life in “The Lost Landscape”?

Charlie reads everything I write, as soon as I write it. He is my “first reader.” He is a voracious reader & intellectual, though a neuroscientist he is at least as interested in politics, history, photography & literature as in science. My image of Charlie is standing with the New York Review of Books in hand avidly reading an article, scarcely aware of his surroundings. He is a close, intense reader & thinker & also a considerable photographer.

There’s a separation between Joyce Carol Oates or JCO as you often call her — well-known writer, someone with best-sellers, someone who goes on speaking tours, someone you’ll refer to in the third person — and Joyce Smith, who has been you “off-stage,” not famous (at home, teaching). Are you still Joyce Smith or are you now Joyce Gross?

You say many of your students don’t read you and may not even know who you are off-campus. It seems like you’ve worked that separation of self for years. Why have you done that and how does it work for you?

I am not sure that any of this was ever intentional or conscious. I was “Joyce Smith” at the U. of Detroit when I first began teaching in my early twenties; then, “Joyce Carol Oates” at the U. of Windsor, and beyond. My passport name is “Joyce Carol Smith.” (I am not ever “Joyce Gross.”) I never discuss my own work with my students — it is just not a good idea to talk about oneself in such circumstances. (Of course it’s different when I visit campuses as a visiting writer.)

As you note in “The Lost Landscape,” many writers seem to have difficult relationships with their parents and their writing is a way to bust out and away from them, exorcise demons or what have you. Not you.

One thing I like about “The Lost Landscape,” is the homage paid to your parents — not at all in a Pollyanna-esque way and certainly you lay out some family history that maybe isn’t so benign. But I think part of what you accomplish here is rescuing the writer’s memoir from the notion (or fallacy) that the best (deep, dark) writing comes from pain suffered in childhood.

There was much anxiety in childhood, but not from within the family; the family was a kind of island or oasis of calm, nurturing, & love. I am naturally very sympathetic with individuals who have come from broken or dysfunctional homes & am in awe of their courage. Writing "Blonde," for instance, the story of Norma Jeane Baker who becomes “Marilyn Monroe,” took me deep into the heart of a childhood not my own but not so different from the childhoods of some of my friends.

At one point in “Widow” you write, in effect, what’s the point of writing a memoir if you’re not telling the truth. But then in “Lost Landscape” you say at the end, some of the people were composites. Is there a contradiction there?

Why? The composites are all “true” enough. I am more drawn to situations than to individuals, if the situations are exemplary & representative. None of the people in my life were celebrities — there is no gossip element here. If the theme is childhood molestation by a parent, that is the preeminent interest, not the identity of an actual girl. I always think of William Carlos Williams’ poem — “The pure products of America go crazy … ”

And, following up, I was very moved by reading of the suicide at 18 of your friend Cynthia. At the end, though, we read that she and several of these people (though not your sister) are composites. How are we to ascertain, then, the truth of the matter? Or is it not important in the scheme of things — that the characters are composites and identities shielded? Did you not want readers to know that going into the book?

The afterword makes clear that names are changed, etc. That this is not a strictly factual memoir might be suggested by “Happy Chicken” — a chapter narrated by a chicken. As Mark Twain said, everything here is true but there might be some stretchers. …

You excel at complex physical and emotional descriptions in your novels and again here, such as when you describe your step-grandfather, there’s the mix of the ugly and the attractive. Your power of observation and description would seem very acute. Is this something you always had or you developed as a writer?

Well, my child-memories are very visual & vivid! I can “see” people like my grandfather Bush very clearly.

I often wonder sometimes about conversations recalled, apparently verbatim in memoirs. Obviously, you reconstruct them. Do you think there’s the tacit agreement with the reader that these are maybe not exact but close — or what you recall many years down the road?

This must always be the case, otherwise no one could quote anything.

Last month on “Jimmy Fallon” Salman Rushdie talked about spending three years writing his memoir — all that time trying to accurately portray what happened — and then said, “I’m sick of the truth. I want to make s-- up.” Your thoughts?

Not sure what to think. Some readers who know Salman were shocked by his depiction of his former wives, especially Marianne. Not sure why an ex-husband would wish to write in such a way, especially one who enjoys such literary fame and power. Perhaps he felt revulsion for such “truth-telling” & has regretted exposing so much of both himself & his ex-wives in print.

You jest (I think) a bit in your book about your prolificacy and seem to poke fun at that frequent description by critics, but truly your output is Stephen King-like remarkable — quantity and quality. Do you feel there ever will come a point where you’ll want to put that aside — retire, if you will?

I love to read & to write. Not sure why I would want to cease writing any more than to cease reading.

A writing question: You use italics a lot. What do you like about their usage?

Style is some sort of mimicry of the (fictive) individual’s thought-processes. It is not my own writing style but a way to express a character.

You write “Our lost selves are not really accessible. Our memories are fabrications, however well-intentioned. And so the effort turns upon itself like a Mobius strip, shrinking from its primary subject. I have been paralyzed by the taboo of violating the privacy of persons close to me and by the taboo, which seems a lesser one, of violating my own self, exposing my very heart, vulnerable and pulsing with life.”

So, there’s a question of how much to reveal to be honest and true, but not being invasive — a balancing act — and the realization that what you write is almost by definition a fabrication.

Yes, much memory is incomplete if not fabricated. (I am married to a neuroscientist & I am afraid that this is true. Much, much of what we think we know is probably not so true, yet we cling to it, we insist, as if our very identities are bound up with it, like eye witnesses continuing to insist that they have identified the correct perpetrator even when it is pointed out that they were mistaken.)

Before book tours were so common, I think authors were much more private, solitary. Now that this is de rigeur, is this a good thing or is it more a necessary burden? You write, in “Lost Landscape” about selling fruits and vegetables as a kid: “Sitting at a roadside, vulnerable as an exposed heart, you are liable to such rejections. As if, as a writer, you were obliged to sell your books in a nightmare of a public place, smiling until your face ached, until there were no more smiles remaining.”

I’ve never gone on much of a book tour. Usually just single-city visits, one at a time scattered over a period of months. People who come to readings are self-selected; it is a little different from the roadside stand past which strangers drive blithely.

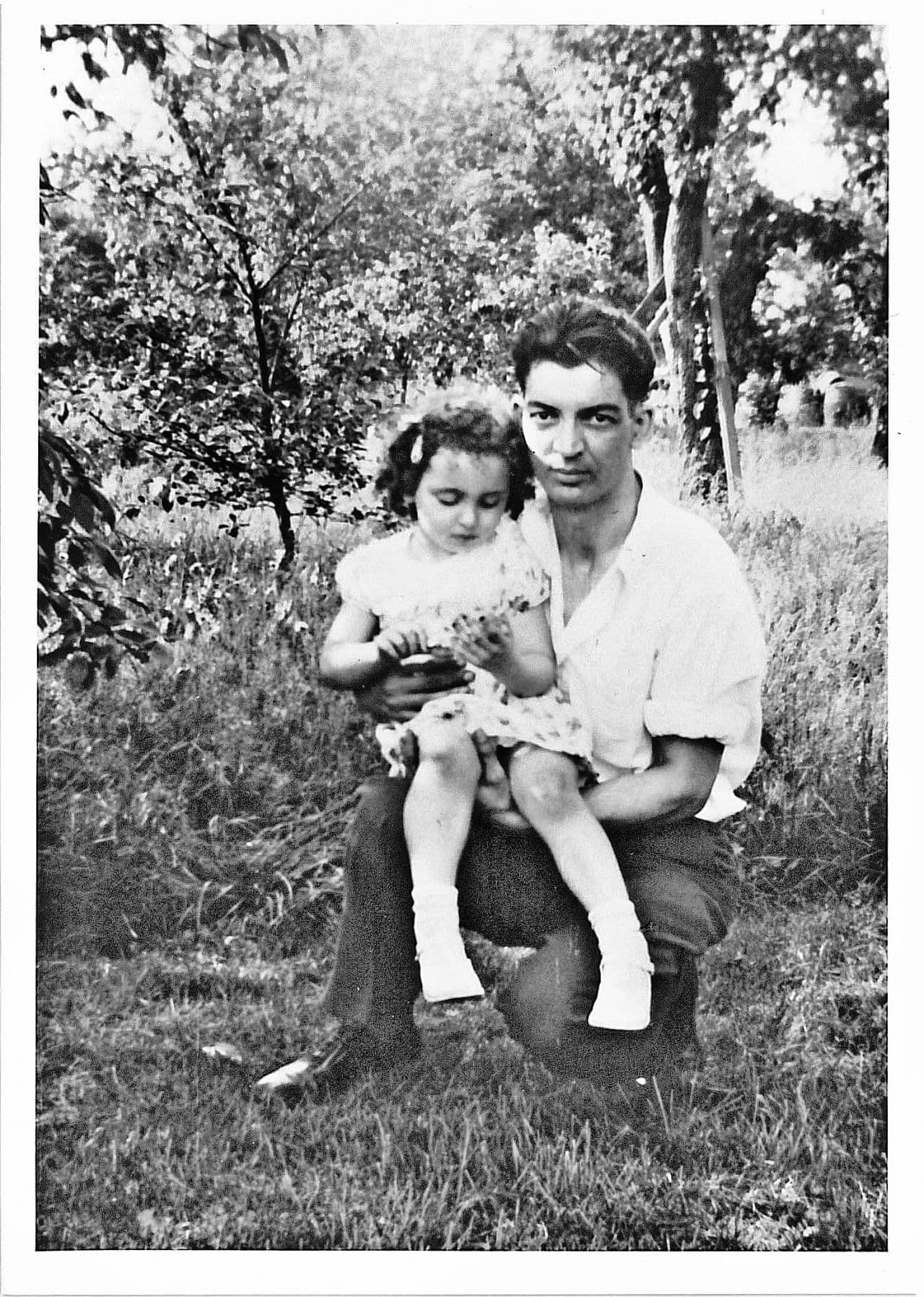

I am, often, a pop music writer/critic and I loved your description of what music can do, writing about your father Fred’s playing and the fact how his upright piano holds a place in your memory: “For a musical instrument — piano, violin — inhabits a complex sort of space: it is both an ordinary three-dimensional object and an extraordinary object, a portal to another world; it exists as a physical entity solely so that the physical can be transcended.”

Yes, I love music though I play piano very imperfectly and even my father — who was no perfectionist — would probably wince at my eroded “technique.” … However, music should make us happy & lift our spirits.

What’s next for JCO fans and readers? Is another memoir in the cards, or, like Rushdie, are you back at fiction? And where do you think you might take us?

My next book is “The Man Without a Shadow,” a novel based partly upon the most famous amnesiac in history, “H.M.” The amnesiac “man without a shadow” of my novel suffers severe memory loss and an inability to process long-term memory; he is studied by a (woman) neuroscientist who makes of him a career, even as she falls in love with him (or with her idea of him). Damage to the hippocampus in the brain results in the inability to process new memories — in the case of my character, he is infected with encephalitis, which causes his brain to swell. (H.M. was an epileptic, and his amnesia was caused by psychosurgery.) I have written on neuroscientific subjects before — my story “A Hole in the Head” is included in the collection "The Corn Maiden" -- but this is my first attempt to so intimately trace the experience of a neuroscientist. Of course, I had access to my husband’s science and medical library, and he was kind enough to proofread my manuscript.

Joyce Carol Oates reads from "The Lost Landscape" at First Parish Church in Cambridge, presented by Harvard Book Store, on Monday Oct. 19 at 7 p.m. Tickets available on the Harvard Book Store website.

Jim Sullivan is a former Boston Globe arts and music staff writer who pens the arts-events website jimsullivanink.com and contributes to various publications, TV and radio outlets. He hosts the monthly music/interview show “Boston Rock/Talk” on Xfinity On Demand.