Advertisement

'Mr. Burns' Dazzles At The Lyric: It's The End Of The World As We — Doh! — Know It

BOSTON — The world as we know it has come to an end. Now it’s time to rebuild. What vestiges of civilization do the survivors cling to and use as raw material to rebuild society and culture?

How about this (sing it, now): “The-e-e Simmp-sons!”

That’s the concept behind Anne Washburn’s unapologetically provocative “Mr. Burns: A Post-Electric Play” (through May 7) at the Lyric Stage Company of Boston. As the lights come up … well, as they go out, really, to be replaced with the orange glow of a trash can fire and a murky ambient illumination that suggests starlight (kudos to lighting designer Wen-Ling Liao)… we meet a group of survivors, a haggard and frightened bunch huddled in a park.

Matt (Joseph Marrella) entertains his companions with a retelling of an episode of the long-running Fox animated sitcom. As Matt stumbles through the episode’s beats, the others join in, jogging his memory and asking him to clarify different points. Maria (Lindsey McWhorter) seems the least familiar with the show, though she recognizes the movie the episode in question parodies: It’s “Cape Fear,” or rather Martin Scorsese’s 1991 Robert De Niro remake of the 1962 Gregory Peck and Robert Mitchum thriller directed by J. Lee Thompson. (The original movie was, in turn, adapted from a 1957 John D. MacDonald novel titled “The Executioners.”)

The others in the group are Jenny (Jordan Clark), who seems very cozy with Matt; Sam (Brandon G. Green); and Colleen (Gillian Mackay-Smith). When a man named Gibson (Nael Nacer) happens upon the group, they nervously draw firearms; the world is now a dangerous place, inhabited by shell-shocked and jittery people. Luckily, Gibson is good at imitations and he knows the episode Matt has been describing. Once he fills in a forgotten punch line, Gibson is accepted into the protective embrace of the others, where he remains.

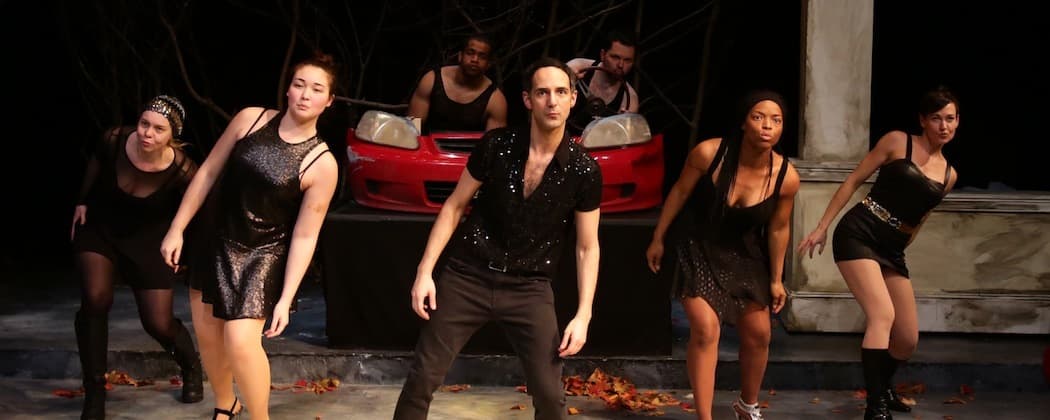

Seven years later, the world has started to recover — enough so that our tiny band of survivors now make a living touring their act, which re-creates not only episodes of “The Simpsons,” but also the overall experience of watching television, commercials and all. (They also do a mean, funny mash-up of popular songs, a medley that includes old hits like “Milkshake,” “Hey Ya,” and “Single Ladies.”)

The world is still a shaky place, but commerce of a sort has been reestablished; the troupe reconstruct “Simpsons” episodes by buying lines and snippets from survivors who recollect the missing bits (batteries seem to the favored currency). Business is good enough that the group can afford a decent set and even a new addition to their number, an actress named Quincy (Aimee Doherty), who appears to have replaced Jenny as Matt’s squeeze.

It’s a dazzling, dazing production that yanks the rug out from under its audience not just once, but a couple of times. Going in, the average attendee might be thinking about post-apocalyptic scenarios we’ve seen before, like the aftermath of nuclear war (remember “On the Beach?”), universal power outages (as in the short-lived television drama “Revolution,”) global pandemics/crop failures/social breakdown (“The Road”). “Mr. Burns” takes bits and snippets of all those things, creating a comprehensive catastrophe in which a plague kills millions, understaffed nuclear reactors melt down and kill thousands more, and a combination of commercial implosion, governmental collapse, and anarchic chaos does the rest. Soon, the world’s population has plummeted.

But this isn’t a story of scrappy survivors and marauding attackers. “Mr. Burns” has larger ambitions, and the play isn’t afraid to confound the usual shape and focus of dramatic narrative. The characters are so deftly drawn that we know (or infer) quite a lot about them in a short space of time, thanks in part to Washburn’s writing but also because the cast is excellent without exception. Still, they and their travails are not the point. What Washburn wants to explore is the central place in human life occupied by literature – a category that here forsakes snobbish narrowness and expands to include television and movies.

How do stories change over time, and how do they incorporate the concerns of any particular age? Bards of old sang “The Iliad “ to rapt listeners, who memorized and repeated the epic to fresh ears as centuries passed. Songs became poems, and oral traditions were written down, then translated, printed, and stored on library shelves. Novels become movies become remakes become TV parodies. But what about the reverse process? How does the contemporary novel, or the moving picture, translate for generations living in an energy-depleted future?

When Act III leaps forward another 75 years, we get a glimpse of how “The Simpsons” has mutated into a cornerstone for a still-traumatized culture. The show’s characters remain recognizable, but they have changed in significant ways, and two of the show’s secondary characters have become conflated in order to create a monstrous new version of the titular Mr. Burns. The power plant owner and sadistic one-percenter now serves as the villain in what can only be described as a 22nd Century morality play, a musical melodrama that cannibalizes and repurposes popular entertainment from a lost golden age. (Scenic designer Shelley Barish and costume designer Amanda Mujica knock themselves out to supply the right blend of the familiar and the garbled.) The cast members now don masks (the work of Lauren Duffy), as if in salutation to ancient Greek theater. Deliberately ragged music accompanies their performance (music director Allysa Jones gleefully makes Michael Friedman’s score sound a little rustic). At this point, we’re not even in the ruins of Kansas any longer. We’ve reached what might be the essential and unchanging kernel of literary and theatrical tradition.

This radical departure is the hardest thing to swallow about “Mr. Burns,” and the most jolting. What happens to Matt and Jenny and Sam and all the others? Washburn ends their story on a cliffhanger before flinging us into a landscape of mangled recollections. Director A. Nora Long maintains a feeling of conceptual continuity despite the jump; you can sense how what came before informs this otherwise-independent segment. Underneath Act III’s stage play from a post-technological era there lurks another story, one comprised of implicit questions: Does the literature of the future look back with regret and longing on how we live now? Or does it pass judgment on our consumerist way of life as an unsustainable chapter in human history that is destined to — indeed, deserves to — come crashing to its end?