Advertisement

There's A Big Gender Gap In Key Theater Jobs — Can Boston Change The Story?

Resume

Certain circles in the nation’s professional theater world have taken to an unofficial ritual in recent years — watching for the annual wave of season announcements from theater companies, and then publicly bemoaning the lack of female playwrights. And directors. And, for that matter, artistic directors.

Thinkpieces are written. Tweets are fired off. But change comes slowly, if at all.

Anecdotal observations are backed up by some stark statistics. A study released by the League of Professional Theatre Women in October, focusing on New York City theaters, found that divisions of labor at theater companies appear to be highly gendered. In the past five years, women accounted for 72 percent of the stage managers and assistant stage managers tallied; just 33 percent of directors were female.

As recently as the 2013-'14 season, there were no new plays by a female playwright produced on Broadway. And the problem isn’t that good plays by women aren’t out there — in 2014, the Pulitzer Prize for Drama went to Annie Baker, while the two other finalists were plays by Madeleine George and the team of Lisa Kron and Jeanine Tesori.

An in-progress study at the Wellesley Centers for Women at Wellesley College looks squarely at gender parity — or lack thereof — in theater leadership around the country. It quantifies some of the difficulty women have in rising to top jobs in this industry, and also finds that the issue is magnified for people of color, both male and female.

A look at the leadership of Boston theaters shows that these national trends are reflected here as well. But evidence suggests that local theater artists are making progress in some areas — and possibly indicating a new way forward.

“It’s not a new issue,” says Ineke Ceder, who co-authored the Wellesley study with Sumru Erkut, about the problems faced by women in theater. “Since the ‘80s, people have been looking at this and saying ‘Hmmm, what’s going on here?’ ”

Their study, set to be fully unveiled at the Theatre Communications Group’s annual conference in June, examined the staff population at the 74 member theaters of the professional organization known as the League of Resident Theatres. Eighty percent of these theaters had male artistic directors. Among them, only five men of color held that position, while just one woman of color did so. Among executive directors — business chiefs at theater companies who are separate from the artistic leadership — 74 percent were men. There were no men or women of color in that role.

Erkut and Ceder stress that it’s not a “pipeline” issue. Women are already plentiful in the field — in fact, they outnumber men as department heads at every level except that of artistic director and executive director. “There are women who are trampling against that glass ceiling,” says Ceder, “who are ready to go, and who are in those theaters and who are qualified and have the aspiration and the ambition and the skills to be in the top position.”

Only three theaters in Massachusetts — American Repertory Theater (A.R.T.), Huntington Theatre Company and Merrimack Repertory Theatre — are members of LORT and thus included in the Wellesley study. But the trends identified by Erkut and Ceder are reflected in Boston theater generally — particularly among the largest, best-funded theaters. Among 11 large- and midsize-theater companies here, just two have female artistic directors. None are people of color.

Trends like these are of course not confined to the theater world. But the disproportionate presence of male voices at the tops of theater hierarchies is especially problematic when one looks around at who is sitting in the audience.

“I think we know that the folks who tend to drive ticket sales — and the folks who tend to push it from ‘I [heard about] this and I’m interested’ to ‘I’m going’ — tend to be women, who are driving the market,” says Summer L. Williams, one of the city’s rising directors and a co-founder of Company One Theatre.

A study released by the Broadway League in January finds that 68 percent of Broadway audiences last season were female. The same percentage was found in a 2010 study of gender breakdown among theatergoers in London's West End.

“Women have such a strong presence and they’re such a core part of the audience,” says Polly Carl, co-artistic director at ArtsEmerson, “so it seems weird that the people making decisions about what stories we tell onstage in leadership positions around the country” include so few women.

ArtsEmerson’s trio of equal leaders is uncommonly diverse with respect to both race and gender.

“We have a tall white guy, we have a short transgender person and we have a sort of medium-sized black man,” says Carl, who identifies as that short, transgender person. Carl shares the artistic director title with David Dower, the “tall white guy” in question. David S. Howse, an African American, is executive director.

When planning seasons, the trio has a system in place to be sure ArtsEmerson works with men and women of assorted backgrounds — they keep track of it on a “diversity grid.”

“That’s intentional work you have to do,” Carl says. “You can’t just be ‘looking for the best person.’ You have to be intentionally thinking, over the course of the all of the work you do, about who are the best people but also, how are they a reflection of where you live and work?”

When women do run the show, opportunities for other women tend to multiply.

Diane Paulus, the A.R.T.'s Tony Award-winning artistic director, is currently directing the musical “Waitress” on Broadway, after helming its world premiere last year in Cambridge. It is the first Broadway musical in history whose director, book writer, composer and choreographer are all women.

“In, say, the ‘70s, women were told they couldn’t be directors. They were told they could be the assistant but not the director,” says Paulus. “I think I benefited from a generation ahead of me who were the first pioneers of women in leadership roles in the arts, and that is so important for where I am today because as a young person growing up in the theater I could visualize myself as a leader in the field — because I had women mentors who were setting that example.”

While men hold most of the top jobs among Boston’s largest, highest-profile theater companies, something may be stirring at the grassroots level. (The theater-size categories referred to in this article are based on those seen in the past five years’ worth of Elliot Norton Awards nominations; the distinctions among them, though, are fluid.)

The Wellesley study finds that women in theater are increasingly taking things into their own hands — when 1,000 current or former artistic directors around the country were asked what skills they felt were most important in getting hired, the top answer for women was that they’d founded their own company.

That’s the case at Bridge Repertory Theater, now in the midst of its third season. All three of its productions this season are directed by women. Producing artistic director Olivia D’Ambrosio says her team is not looking to fill quotas — but a female-led company is simply more likely to be cognizant of talented women in the field.

“It’s not a stated part of our mission to meet any sort of parity quota, and we don’t give ourselves any special points for doing it,” she says, “it’s just an inevitable outcome of who we are.”

Fresh Ink Theatre Company, founded in 2011 and dedicated to new work, has an all-female leadership team; it too is going three-for-three this season with female directors. Apollinaire Theatre Company, Nora Theatre Company and Fiddlehead Theatre Company are among the small but long-established troupes also led by women.

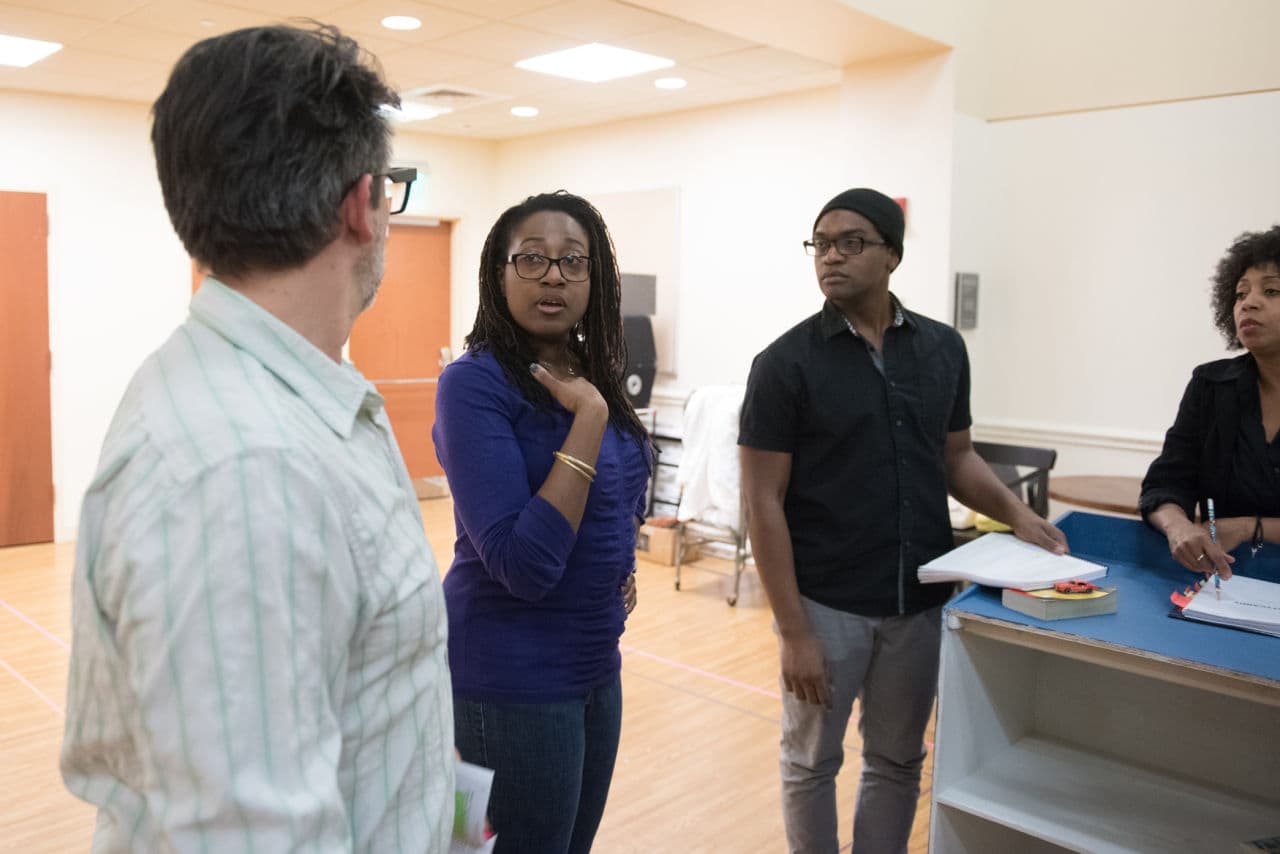

When it comes to gender parity locally, women directors and playwrights do seem to be the ones leading the charge. Huntington Theatre Company and Company One recently received hefty grants to employ Melinda Lopez and Kirsten Greenidge, respectively, as full-time playwrights-in-residence. Women are among the scene’s busiest directors. There appear to be only four directors who are helming shows at multiple Boston theaters this season. Three of them are women — Williams, M. Bevin O’Gara and Bridget Kathleen O’Leary.

“It’s great to have a cohort, if you will,” says Williams of her directing peers, “and to have women run some things on Boston’s stages. That’s a very important step.”

Trends like these are still exceptions to the norm. But they could indicate that, just maybe, Boston is starting to write a new script for women in theater.