Advertisement

A Soprano Song Of Searing Passion And Heartbreaking Honesty — Remembering Phyllis Curtin

The music world lost one of its great artists and great souls Sunday, when soprano Phyllis Curtin died at her Great Barrington home at the age of 94. She seemed ageless, as if she could go on forever. I’d like to think that she still very well may — through her recordings, her students and for those of us with indelible memories of her performances.

Here are some of my fondest memories of her. Although she was probably better known as a singer of Mozart — her belated Metropolitan Opera debut was as Fiordiligi in “Cosí fan tutte,” in 1961 — I’ll never forget her as Wagner’s Senta, the heroine obsessed with the legend of the Flying Dutchman, in Sarah Caldwell’s inspired 1970 production, in which the director convincingly transformed MIT’s Kresge Auditorium into the Dutchman’s ship.

Curtin, mesmerized and mesmerizing, was in heartbreakingly magnificent voice. At the Met, she was perfectly cast as Ellen Orford in Benjamin Britten’s “Peter Grimes,” infinitely touching as the one person in the small-minded sailing village who believes in the hapless hero. And she always spoke with the same honesty, luminosity, and humanity she brought to her singing. You always knew that she felt that what she sang was more important than projecting an ego or making an impression.

Curtin was famously dedicated to performing contemporary music — she’s quoted in her New York Times obituary saying she gave “more first, and last, performances than any singer in history” — and she created a number of important roles. The best known of these was the title character in Carlisle Floyd’s “Susannah” (1955), an Appalachian retelling of the biblical story of the chaste wife falsely accused of lechery by two elderly voyeurs who’ve been watching her bathe. On a CD of a 1962 New Orleans performance released by VAI, she’s incandescent — at the top of her powers and in thrilling voice. Her voice evoked searing passion and exquisite delicacy, especially in two of the few contemporary arias that have actually entered the standard recital repertoire: “Ain't it a pretty night” and the even prettier folk song “The trees on the mountains.”

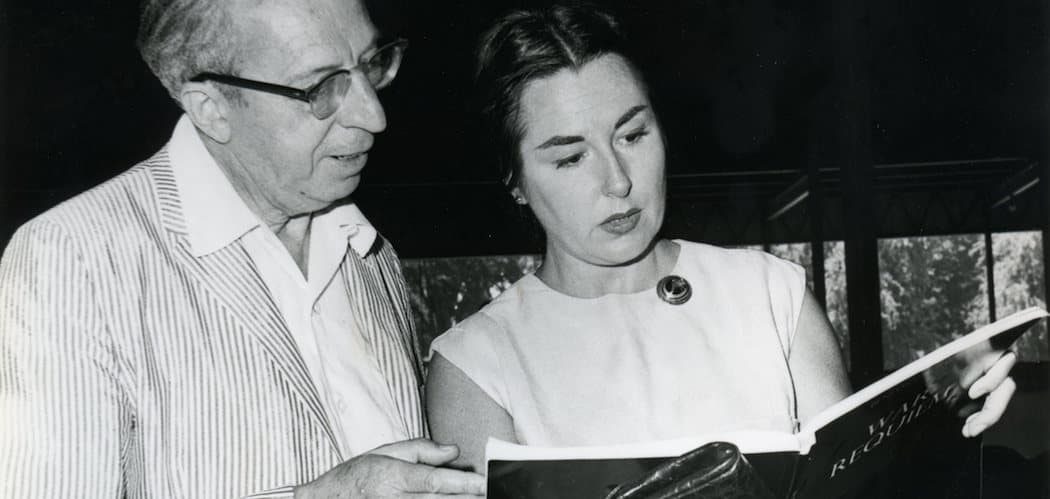

Graduating from Wellesley College, she maintained a close affiliation with Boston. As a vocal student at the Tanglewood Music Center (TMC) in 1951, she appeared often with the Boston Symphony Orchestra. (She sang at Tanglewood more often than at Symphony Hall.) In the summer of 1974, I heard her in Lenox in Schoenberg’s “Gurre-Lieder,” heading a stellar cast that included the commanding bass-baritone George London as the narrator, powerhouse tenor James McCracken and contralto Lili Chookasian.

In that performance, Seiji Ozawa rose to his highest level of conducting in 29 years with the BSO. Five years later, with a mainly different cast, he couldn’t repeat his triumph. Do I think that Curtin’s extraordinary musicianship had something to do with the overall success of that earlier performance? No question!

For more than 50 years, she taught at the Tanglewood Music Center. (She also taught at Yale, and had been dean of Boston University’s School for the Arts.) At one vocal class I sat in on at TMC, she told her students there was nothing more important than to get the words across — and that, besides, it was actually easier to sing the vowels as written rather than distort them as many of them had been encouraged to do by their voice teachers.

She was a staple of the New York City Opera until she bitterly departed in 1966, when Beverly Sills contrived to get the company to give her a role promised to Curtin, Cleopatra in Handel’s “Julius Caesar” — the role that made Sills a superstar.

I mainly heard Curtin later on in her career. In 1985, at the age of 63, she was astonishing in the soprano role in Shostakovich’s song-cycle Symphony No. 14, with the chamber group SinfoNova. She had sung the American premiere in 1971, and recorded it, so it was clearly a role close to her heart. She sang Lorca and Apollinaire poems in Russian and provided her own English translations in the program. As the suicidal Loreley, she both bitterly lamented (“Three lilies three, three lilies three, on this cold grave of mine”) and laughed at the death of her young soldier with hypnotic expressiveness.

After she officially retired from singing, she unofficially appeared singing seductively stylish Cole Porter (“Love for Sale,” “In the Still of the Night”) with the legendary jazz duo of pianist Dwike Mitchell and bassist/horn player Willie Ruff. And in 1994, in a production at BU, she was unforgettable as the retired old courtesan singing about her “Liaisons” in Stephen Sondheim’s “A Little Night Music.”

Curtin’s suggestive twinkle in both her voice and eye revealed just how she was able to “acquire some position, plus a tiny Titian” and how when “things got rather touchy” with the King of Belgians, he “deeded her a duchy.” Her world-weariness was also bone-chilling.

I haven’t been able to find much of Curtin’s singing on YouTube. But an album called “We Wish You a Merry Christmas” (listen to the audio above), led by pops arranger/conductor Andre Kostelanetz, gives you some idea of Curtin’s crystalline tone and personal warmth. At about four minutes into the recording, she sings “What Child Is This?” to the tune of “Greensleeves.”

It doesn’t tell you everything you need to know about Phyllis Curtin, but even this commercial Christmas album tells you a lot.

Correction: An earlier version of this story had Phyllis Curtin dying on Saturday. WBUR regrets the error.