Advertisement

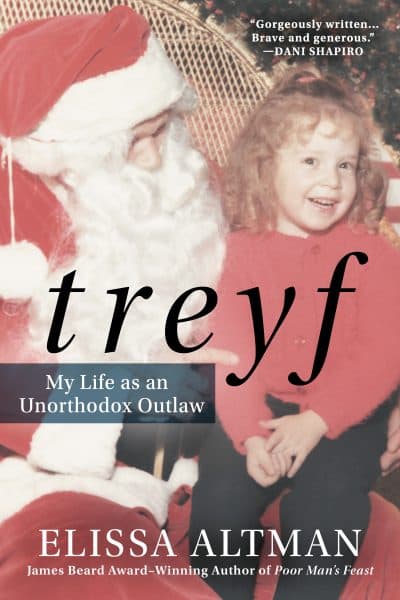

Food Writer Elissa Altman Dives Into New Territory With Family Memoir, 'Treyf'

“A person can eat treyf; a person can be treyf,” declares Elissa Altman’s kosher-keeping Jewish grandmother. And what is treyf?

“According to Leviticus, unkosher and prohibited, like lobster, shrimp, pork, fish without scales, the mixing of meat and dairy. But also, according to my grandmother, imperfect, intolerable, offensive, undesirable, unclean, improper, filthy, broken, forbidden, illicit, rule-breaking.”

These are harsh, visceral words, but appropriate in Altman's latest, "Treyf: My Life as an Unorthodox Outlaw."

Best known as a food writer, Altman has produced a family memoir that is pungent, raw, sometimes hilarious, but never delicate. It’s a story about the allure and limits of self-reinvention, a meditation on how tradition both soothes and imprisons. And because this is a memoir about family, it is also a memoir about food.

Growing up in the late 1960s and 1970s in The Marseilles, a new middle-class fortress in Forest Hills, Queens, Altman straddles at least two cultures. Her father, the son of an Orthodox immigrant cantor and his hausfrau wife, is “a Fifth Avenue mad man ad man of the teak credenza-Modern Jazz Quartet variety.” Her mother, born to a kosher-keeping, Bing Crosby-loving secret lesbian and a gentle but distant Brooklyn shop owner, is a former model and television singer, a glamorous woman who, when young, “gazed at the mirror and dreamt that she was Ava Gardner.”

Daughter of two parents who are estranged from each other and from their own middle-class lives, Elissa rebels against her mother’s attempts to feminize her with Vogue, Harper's Bazaar and strategically placed boxes of Ayds weight loss candies, smokes pot with the bell-bottomed daughter of an Orthodox Holocaust survivor next door, listens to rock 'n' roll and, at her beloved Jewish summer camp, prays and beseeches “How can we know God? Where can we find him?”

On Sundays, Elissa and her parents visit her paternal immigrant grandparents in Brooklyn. These afternoons are “…a car crash of old and new worlds, of schmaltz and Mitch Miller, of Santa Claus and the Cossacks.” While Elissa’s mother longs for return to her more cosmopolitan life, her father yearns for the attention of his father, who “lays the Torah on his shoulder so tenderly, like a baby, as he floats up and down the aisles of the airless synagogue, his eyes closed in a meditative trance … Tears cascade down his cheeks as he passes his son … He floats past my father like a ghost.”

As a younger man fleeing reverence and rage, her father enlists in the military. One night, after a particularly wrenching visit home, he dines in the officers’ club in Corpus Christi, gorging himself on prawns, pate, ribs and German sausages. “He eats all of it with a combination of rage and fervor; at first, it tastes bitter and alien, but then washes his father’s rejection clean and leaves in its place the sweet flavor of acceptance and belonging. He has broken the code and scoffed at the law; he is a Jewish boy dressed in an American Naval uniform, living and eating like the Gentile everyone on base will believe him to be.”

If you’re a Jew, it’s impossible to read this book and not burn from the repeated shocks of recognition. But it’s equally impossible if you’re a woman who was once a daughter, if you’re anyone who’s ever been an adolescent at almost any time in the past few centuries. The parental quarrels. The food — the endless plates of food, so much of it forbidden. The beige enema bag suspended upside down from the shower nozzle in her grandparents’ apartment, the box of passed down silver ornaments, “the smell of the past — a gamy, transportive scent of despair and schmaltz and Aqua Net,” — these are the details that make "Treyf" so extraordinarily resonant.

With skill, pathos and subversive wit, Altman depicts her parents’ and her own conflict between individuation and belonging, between being American and being imprinted with a tribal affiliation far less shiny and new. Just witness her father’s possessions: "Until he moved out, and for all the years of my childhood, my father kept his copy of 'The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich' on the top shelf of the Danish Modern etagere in our living room in The Marseilles, sandwiched between 'Portnoy’s Complaint' and an ebony bust of the Buddha."

Altman depicts her mother and grandparents with clarity leavened by compassion. But it’s her ambivalent father, Cy, the Burberry-wearing, treyf-eating, secretly praying ad man who most comes alive on the page. And right from the beginning of the book, we know why. Like Cy, Elissa is an outsider simultaneously yearning to break in and to break free. The first Thanksgiving after she comes out as a lesbian, as she carries plates into the kitchen, her Aunt Sylvia whispers to her, “Who do you think you are, to cheat us out of joy, to break the chain?”

The author, her conflicted father, her glamorous, self-starving mother, her friends who chant from the Torah on their bat mitzvahs, then celebrate with shrimp-in-lobster sauce at their post-shul luncheons at the Tung Shing House — they are all modern Americans alternately fleeing and embracing identities rooted in the ancient. And as Elissa observes of her father and herself, “He gravitates to places where no one knows him, where he — where we both — can start fresh: new lives … we wait, anxiously, for the world to change around us, to accept us, to approve.”

Elissa Altman will be doing two readings in the Boston area: Wednesday, Oct. 19 at Wellesley Books at 7 p.m. and Thursday, Oct. 20 at Brookline Booksmith at 7 p.m.