Advertisement

A Bracing View Of Bloody Rebellion In Abbey Theatre's 'The Plough And The Stars'

The second scene of “The Plough and the Stars” is set in a Dublin pub. It’s 1916, and attendees of a rowdy rally outside are getting swept up in revolutionary fervor. A procession of characters — the young, Marx-quoting ideologue, the habitual barfly who’s forever resolving to stop drinking, the young prostitute frustrated by the lack of business that evening — talk about current events and toss plastic cups to the ground, where they’re stepped on and kicked around and smashed as a quiet sense of menace builds. The center here will not hold.

Periodically, in the bracing staging of Sean O’Casey’s 1926 play directed by Sean Holmes, someone in the pub reaches for a remote control and puts on the TV news, which is carrying rebel/patriot Patrick Pearse’s speech at the rally. “Bloodshed is a cleansing and a sanctifying thing,” he declares, his voice booming in from the rear of the house. It’s clear that the normalcy represented by this pub, laced as it may be with bouts of narrowly avoided fisticuffs, is soon to be torn apart.

If more of this production, which originated at Dublin’s Abbey Theatre and can be seen at American Repertory Theater through Oct. 9, maintained this crackling intensity, it might have been thrilling. As it is, the intermittently riveting show is sometimes easier to admire than to enjoy.

Let’s get the provincial quibbles out of the way. When the play debuted at the Abbey in 1926, attendees famously rioted. This wasn’t the flag-waving depiction of the Easter Rising — a watershed event in the prolonged rebellion that led to the establishment of the independent Irish republic in 1922 — audiences had shown up expecting to see. Theater co-founder William Butler Yeats made a speech in hopes of settling people down. By the top of the second act on press night at the A.R.T.’s Loeb Drama Center, many strings of previously filled seats sat empty. Presumably, their occupants did not flee because they were scandalized by the production, but because they had trouble decoding the accents of the performers — particularly when employing period slang. This is a case where (more) amplification would have been helpful.

Divorced from its context, this material loses much of its power. The message — war is bad — lacks nuance and feels heavy handed. And crucially, for the typical Cambridge theatergoer, this is not so much a revisionist history of the Easter Rising as it is an introduction. The historical milieu in which it was written and first performed is almost part of the play itself. Even the most careful program notes cannot replicate that.

Does every play have to have fresh political relevance? Of course not. But this plot isn’t really designed to be riveting; the scenes are written to depict a particular time and place. The characters are all types. It doesn’t seem like there’s a ton to discover about their psychology or relationships; the action is all broadly drawn to serve the playwright’s didactic purposes.

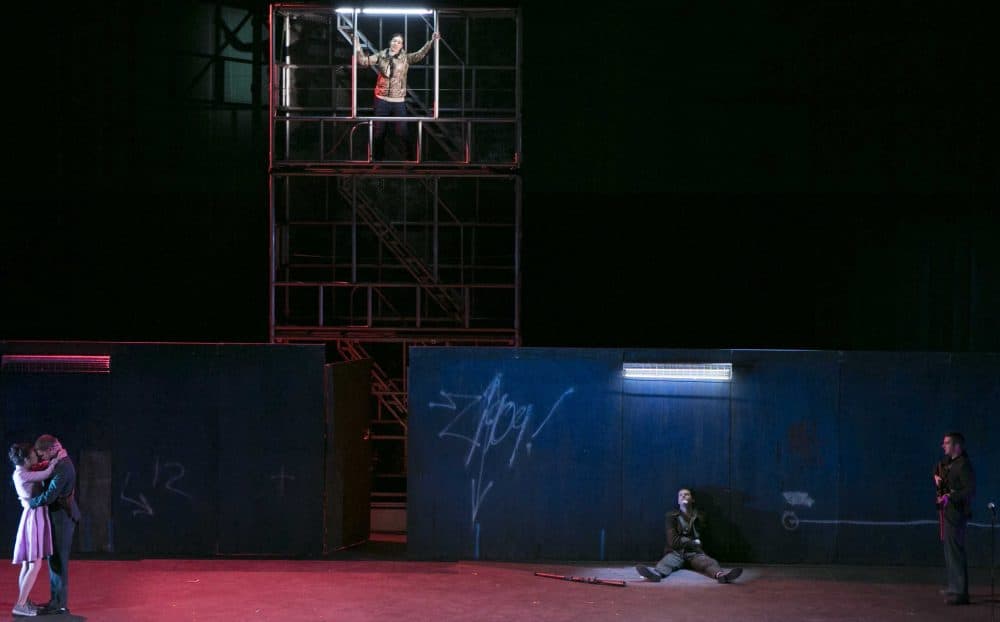

Director Holmes picks up the script by the lapels and shakes it, and this is to the good. Jon Bausor’s stark set design is dominated by a tower of scaffolding, which is repurposed for each scene — here a tenement house stairwell, there an abstract suggestion of an attic. A row of sometimes-flickering fluorescent lights at the stage lip contributes to the illusion of bright, natural light; I don’t believe there were any in-scene lighting cues. Catherine Fay’s costumes are mostly suggestive of the current day. Philip Stewart’s music and sound design gets a lot of mileage from Toydrum’s “God Song,” played at ear-splitting volume.

And Holmes adds an inspired prelude, which I won’t spoil, but which perhaps does more than anything to metaphorically represent the impact the play made on its first audiences. (It also sets up the most quietly moving image of the show, kicking off the final scene. This production is best at its moodiest.)

As written, the play isn’t really a showcase for actors. Each character generally has two modes: some dominant characteristic, and histrionics. As Nora, Kate Stanley Brennan is one of the few who is given conflicting emotions; it’s a scenery-chewing role, and Brennan does well with it. Janet Moran is funny as the busybody Mrs. Gogan; David Ganly is a jovial Fluther Good; Hilda Fay hits a believable screech with Bessie Burgess.

The script mixes blood and humor, and Holmes leans into this a bit too hard, with bold but jarring smash-cuts between scenes of tragedy and broad humor making it hard to maintain either emotional pitch. He has a good eye for stage pictures, though, and even the stark setting has a sense of the epic to it that befits the subject matter.

This is definitely a vision of “The Plough and the Stars” drawn in bold strokes. Yet some parts of it remain hard to see.