Advertisement

New Hip-Hop Archive Is A Time Machine Back To The Electrifying Early Days Of Boston Rap

Resume

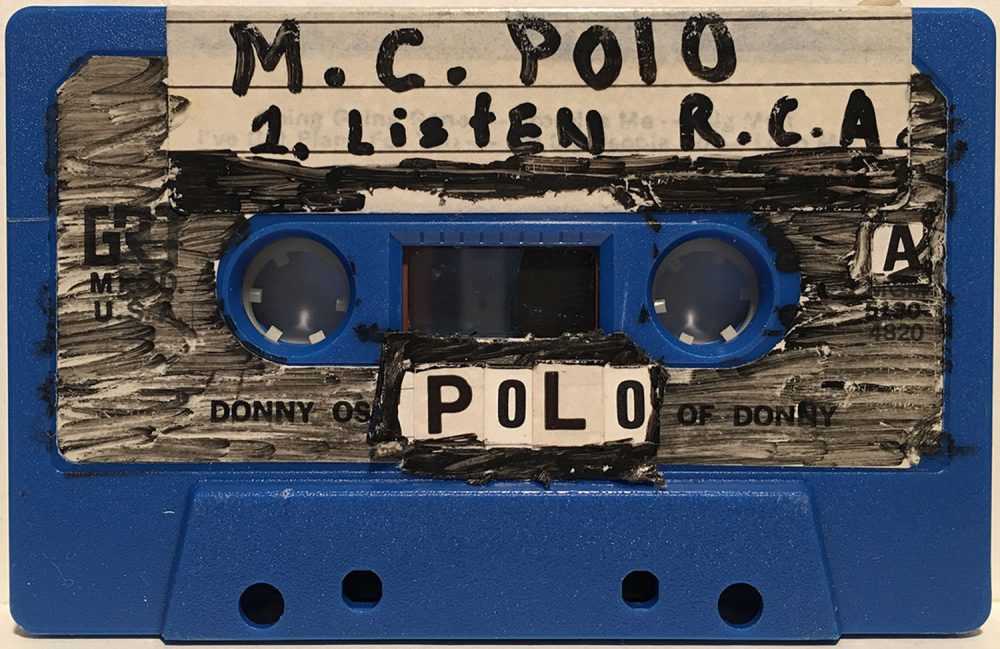

In 1985, a radio show called “Lecco’s Lemma” on WMBR became ground zero for Boston’s burgeoning hip-hop scene. Rap was just starting to break into the mainstream, and kids from the city to the suburbs were catching the bug. Local rappers flooded the MIT radio station with demo tapes in the hopes that the show’s host, Magnus Johnstone, would play them on the air.

On Saturday, Nov. 19, some 300 of those tapes, along with a slew of recordings of the show itself, will be made available online — for free — with the launch of the Massachusetts Hip-Hop Archive at the University of Massachusetts Boston. An event from noon to 5 p.m. that day at the Boston Public Library in Copley Square includes panels with a number of movers and shakers from the early days of Boston hip-hop, including underground rappers Edo. G and Akrobatik, and DJ Rusti “the Toe Jammer” Pendleton.

The digitization process was made possible by a grant from the Boston Public Library. The archive is unique among its peers — Harvard’s Hip-Hop Archive & Research Institute, for example, is more focused on research and commercial releases. “Not only is hip-hop an important, but not very often discussed, part of Boston’s music history, this particular project really delves into the neighborhoods of Boston and how they're different,” says Michael Colford, director of Library Services at Boston Public Library. “We figured this archive would really allow for research opportunities into the neighborhoods of Boston, in addition to race issues and gender issues and other musical explorations.”

The seeds of the Massachusetts Hip-Hop archive were planted nearly a decade ago, when UMass Boston professor of management Pacey Foster was working on an academic article about Boston hip-hop titled “Hip-Hop in the Hub: How Boston Rap Remained Underground.” Foster was interested in interviewing Johnstone for the piece, so he drove up to Maine to visit the former radio DJ at his home. Johnstone, who passed away in 2013, was still in possession of a large collection of old demo tapes from his “Lecco’s Lemma” days. Foster knew that digitizing them all would be a task — but he also knew the tapes contained something special.

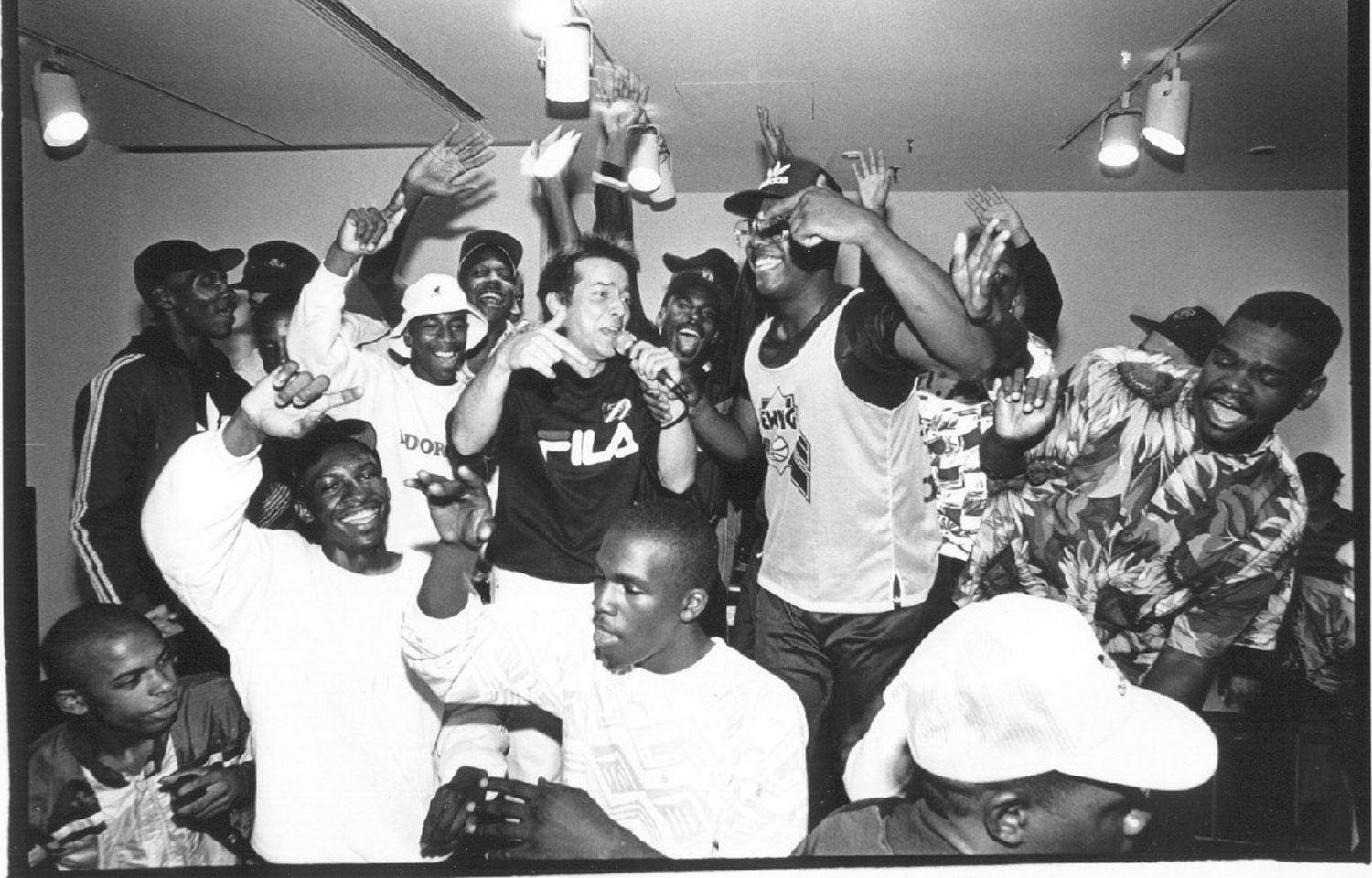

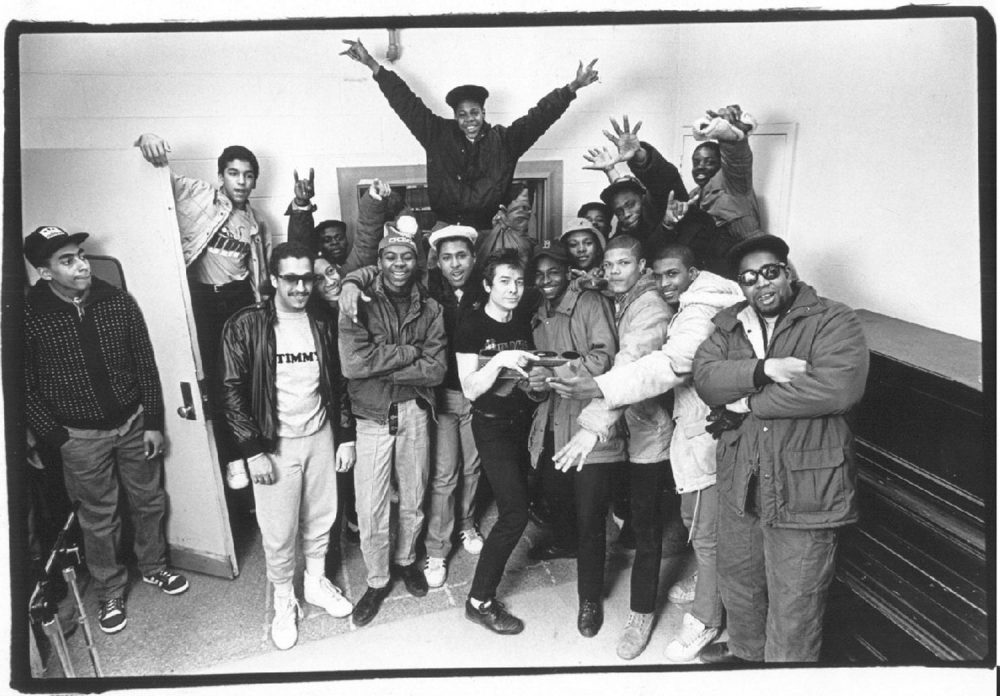

"That was right when hip-hop was busting out and becoming a mainstream, a broader youth phenomenon,” Foster says. “These are really unformed artists. Literally 13, 14, 15 [years old]. [Johnstone] just gave them a platform, put them on with all of the rough edges and craziness that comes along with that. And what I've come to realize is he was essentially running an evening youth center at WMBR in the basement of the Walker Memorial Building.”

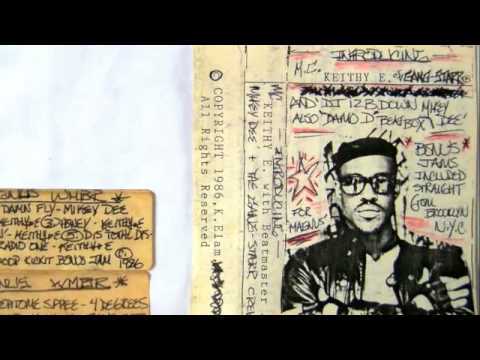

“Lecco’s Lemma” was a loose, scrappy affair. Johnstone would invite young rappers to the station to give of off-the-cuff interviews and perform jokey freestyles. Edo. G got his start on “Lecco’s Lemma” with the Fresh To Impress crew (FTI), and The Almighty RSO, who became famous (or infamous) for their early 1990s song “One in the Chamba,” appeared on the show numerous times. The archive even boasts an early interview with the legendary rapper Guru, then known as Keithy E, who grew up in Roxbury and made his career in Brooklyn. After WMBR cancelled “Lecco’s Lemma” in 1986, Johnstone moved the show to WZBC at Boston College in Newton, where it ran through 1988.

“[Hip-hop] wasn't basketball, it wasn't football, it wasn't any of that,” says Rusti Pendleton, who appeared on “Lecco’s Lemma” as “the Toe Jammer” — he scratched records with his feet — and went on to found the now-shuttered Funky Fresh Records in Dudley Square and the internet radio station Funky Fresh Radio. “We were doing things from the heart, we were doing things because it was fun. … Now is about becoming famous. Now is about making that money. Now is not even about being creative.”

Though Johnstone did not record the show himself, Foster was able to track down a cache of old broadcasts from Willie “Loco” Alexander, a Gloucester musician and prominent ‘80s Boston art-punk, who happened to be a fan of the show. Foster then recruited Sharell Jacobs, a junior at UMass Boston, to catalog the entire collection. It was a laborious task. "It would be a mixtape, and then it would jump into somebody's radio interview, or someone else's new song that they just made at home,” says Jacobs, who raps under the moniker Bay Holla and will sit on a panel at the launch. “So we were hearing a variety of different music — from music that was actually professionally put out, to music that was locally created."

Jacobs also tried to track down as many of the people who appeared on “Lecco’s Lemma” as she could. It was no easy feat — most had not turned pro, and people were scattered far and wide. One of her greatest successes was connecting with an early Boston rapper named Lisa Lee (not to be confused with the rapper named Lisa Lee from the Bronx), one of the few female emcees to emerge in Boston during that time. “It was really interesting to sit down and pick her mind about what the music scene was like in the early ‘80s," says Jacobs. She and Foster intend to continue their research, with the hope of creating an oral history of Boston hip-hop. They also plan to expand the archive, which currently only includes the “Lecco’s Lemma” collection. The Massachusetts Hip-Hop Archive can be explored digitally on UMass Boston’s Open Archives website, and in person by appointment at the Healey Library on the UMass Boston campus.

The event at the Boston Public Library includes a discussion on racism and cultural appropriation in hip-hop lead by Jamarhl Crawford, a Boston activist and rapper, and UMass Boston professor Reebee Garofalo. “If it was a black guy who wanted to have a radio show, we wouldn't even be having this conversation now because it wouldn't have happened," Crawford says. Hip-hop, he argues, may have begun in black communities, but white people — from Eminem to Johnstone himself — have always enjoyed disproportionate power and influence. “The '80s comes along, and me and 'Billy Murphy' both get the same idea at the same time, that we want to rap,” says Crawford, who is black. “Twenty years later, 'Billy Murphy' owns the website, owns the magazine, owns the venue — he essentially owns all the infrastructure that deals with how hip-hop is commodified and commercialized."

Implicit in the archive is the question of why Boston’s hip-hop scene never rose to national prominence, despite showing great promise in the ‘80s. Back then, radio shows proliferated: in addition to “Lecco’s Lemma,” there was “Rap Explosion” on WERS at Emerson College and “Street Beat” over at Harvard’s WHRB; two of the creators of “Street Beat” went on to found the pioneering hip-hop magazine The Source. The city was swarming with fledgling emcees hungry for success, and several, like Edo. G (also stylized as Edo.G and Ed O.G.) and the members of The Almighty RSO, even enjoyed some mainstream exposure.

Crawford blames a lack of industry infrastructure, economic opportunity and business acumen in the local scene. Pendleton says that gang violence continues to fracture the community. Both hope that the Massachusetts Hip-Hop Archive will help instill pride in Boston’s hip-hop history. "Most artists today think they woke up and they were the first cats to start rapping,” Pendleton says. “We're teaching future artists to realize that the city had a history.”

The mere existence of the archive, Crawford says, is significant. “All archives are important,” he says. “Boston hip-hop is a thing — it's worth something. And if something is worth something, it is worth being recorded.”