Advertisement

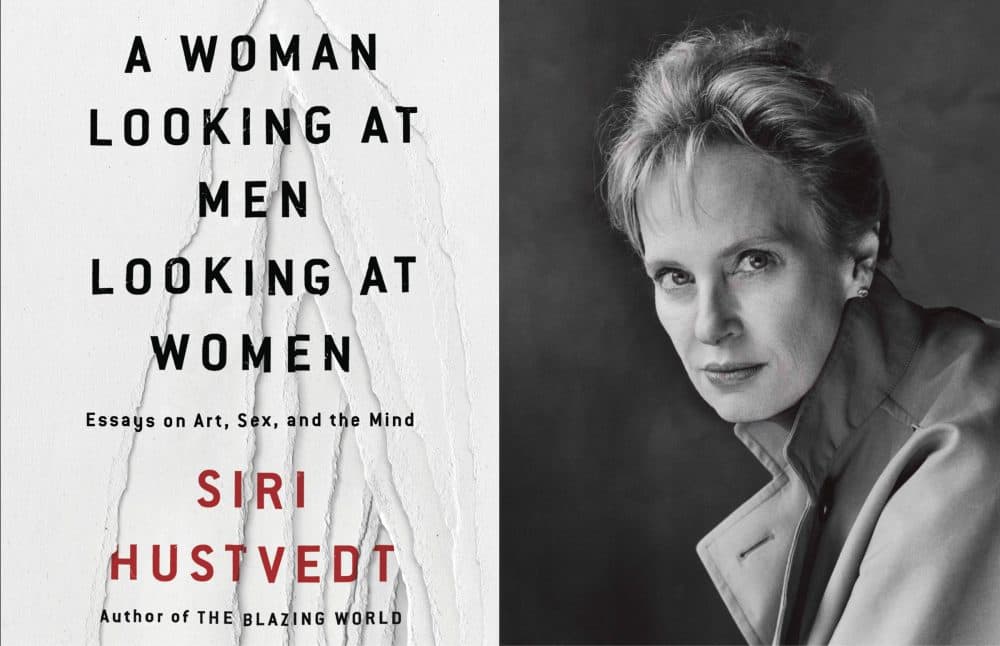

Siri Hustvedt Gives Perception Center Stage In 'A Woman Looking At Men Looking At Women'

It doesn’t take me long to realize I’m in a very meta situation: I am a man speaking on the phone with a woman who wrote a book called "A Woman Looking at Men Looking at Women."

"Absolutely!" says the woman, novelist and essayist Siri Hustvedt. She laughs before shifting gears. The book’s title, also the title of its first essay, "relates to the theme because when one is examining the history of Western philosophy it is startling the degree to which women are marginalized when the topic is specifically about women," she says. "As Simone de Beauvoir so beautifully said, 'Woman as Other,' that she does not stand in for universal experience."

"...when one is examining the history of Western philosophy it is startling the degree to which women are marginalized when the topic is specifically about women."

Siri Hustvedt

"A Woman Looking at Men Looking at Women: Essays on Art, Sex, and the Mind" -- the book's full title -- has three sections. The first comprises 11 feminist essays about art and perception. The second, one long essay, is called "The Delusions of Certainty," considers issues of the mind and the body, and the third is "What Are We? Lectures on the Human Condition," dealing with everything from an analysis of suicide to the history and mystery of hysteria.

Hustvedt, who has written six novels, four books of essays and one book each of non-fiction and poetry, did not just recently jump into the topic of imbalance and sexism in the art world. This book has been in the works for four years and these themes are also at play in her 2014 novel, “The Blazing World.” Her protagonist in the novel, the talented and tempestuous installation artist Harry (Harriet) Burden, is partly inspired by the career of the late sculptor Louise Bourgeois.

In “A Woman Looking at Men Looking at Women,” Hustvedt devotes an essay to Bourgeois and quotes her thus: “A woman has no place as an artist until she proves over and over that she won’t be eliminated.” Bourgeois only found success late in life; she died in 2010 at 98. Hustvedt’s fictional Burden has also been thwarted throughout her career. Despite being a peer of Julian Schnabel and Jeff Koons, her artistic worth is not recognized until after her death at 64.

"I think older women constitute less of a sexual threat," muses Hustvedt. "You become more like a man in some strange way. There’s a sense that a woman in the art world is glaring — a young woman cannot be both an artist and genius and sexually alluring."

Hustvedt says she became a feminist at 14, but it took much of her career to really grasp sexism's impact on her own life.

“I think when I was younger I had a tendency to blame myself for what was simply prejudice. You’d say, ‘Oh gee, I’m not good enough.’ At 61, I’ve done enough work and I have confidence in the force of that work, to be able to identify moments of sexism with some confidence. You realize this has to do with how the world works, that work by women, whatever it is, is in general underestimated or even denigrated. There is what I call a ‘masculine enhancement effect’ that goes across the board from science to literature. And in art, there’s a long history of women being pushed to the side.”

While sexism and critical perception are main themes in her current book, there are others, most crucially, the connection between mind and body — and doctors and scientists’ aversion to considering both. Hustvedt, who in addition to her literary clout is a psychiatry lecturer at Weill Cornell Medical College, writes derisively about doctors who have a “philosophically naïve, hierarchical conception of the physical and psychological.”

The group of essays isn’t purely of literary interest — it’s gotten her an invitation to speak to medical professionals at Longwood and Massachusetts General Hospital this week about the mind-brain gap when considering hysteria. (She’ll also be reading to the general public at Brookline Booksmith on Thursday, Jan. 5.)

"The reason that I was asked to lecture is because I am bringing multi-disciplinary points of view to neurological and neuroscientific questions." Viewpoints, Hustvedt says "that a lot of these doctors and researchers do not hear."

The root causes of hysteria — or "conversion disorder," as Hustvedt says it is called now — is an area of keen interest, and what she’ll be lecturing about in Boston. “I’m talking about how conversion disorder can be located in the place between the mind and the body. We talk about psychosomatic illnesses and the question is: What are we talking about? Is the mind something separate from the body? If you put those multiple answers together, I think you come up with a focused form of ambiguity. Ambiguity can be a rich concept, as opposed to an impoverished one. Knowing what we don’t know is always helpful.

“I think the other part of this is cultural: People do not like the idea of having a mental illness. The idea is that it’s almost as if it’s imaginary, that it’s not real in the way that breaking your leg is absolutely real. They’re all of the body, but they’re of the body in different ways. Part of the problem is that mind-body distinction has become so deep, not only in these disciplines, but in popular culture. If you have a psychiatric disorder that clearly affects the organ of the brain, it doesn’t mean you have a hole in your brain, an actual lesion."

Hustvedt has personally experienced a neurologically unexplainable condition. It happened four times, beginning at her father’s memorial service. An accomplished public speaker, Hustvedt took the podium and began shaking uncontrollably. She could speak, but she shuddered violently from the neck down. Index cards flew from her hands, her arms flapped, her knees knocked, her legs turned deep red with a bluish cast. When the speech ended, the shaking stopped.

She writes about it in the current book and also explored it in 2009’s “The Shaking Woman or A History of My Nerves.”

“The weird thing about it is it is an undiagnosed condition,” Hustvedt says. “Now I think that the conversion features of me shaking are clearly related to my father’s death. But my neurologist does not want to believe they were hysterical episodes and there are reasons to believe that they weren’t. What was interesting to me was it was an ideal opportunity to take my symptom and keep circling it through various points of view.”

One thing Hustvedt would like to do is build a bridge between science and the humanities.

“In some ways, the book is addressing the problem of specialization,” she says. “I would say that until the second world war, there still was an idea in the west of the ‘educated man’ and when I say man I mean man. There were a few women. But mostly there was an idea that people had some access to the history of science, to the history of western philosophy, to great literary works — that knowledge was shared and it made a conversation possible. After the second world war, those people began to vanish. I think what we’re talking about now is that people go into particular fields and they learn everything that they can and the result is they know more and more about less and less.”

“A Woman Looking at Men Looking at Women” is a provocative book, but not a breezy read by any means. It’s perhaps best consumed in chunks. She says she was a bit surprised the publisher, Simon & Schuster, wanted to include the final third of the book, her academic lectures, because they’re not geared so much to the lay reader.

Hustvedt divides her time between fiction and essays.

“Novels are the hardest thing in the world,” she says, “because I have this sense of the essay as a roaming intellectual form, but nevertheless I’m writing in my own voice. When I write in a novel, I’m inhabiting someone else or multiple people. That is both more exciting and more difficult. A novel is an organism and as the organism begins to grow, I hang on for dear life and begin to follow that animal to wherever it wants to take me.”

"Novels are the hardest thing in the world, because I have this sense of the essay as a roaming intellectual form, but nevertheless I’m writing in my own voice."

Siri Hustvedt

She believes, as do many novelists, that truth often can be better told in fiction than non-fiction. “Even if you are mining the emotional terrain of your own life,” she says, “you are not taking people down with you, as a memoir [might], for example. I feel very protective of the actual human beings in my own life and family and I have private feelings about that. Whereas in a novel you can surprise yourself with what I think of as true emotions that are nevertheless coming out of these characters.”

Hustvedt lives with her husband, noted author Paul Auster, in Brooklyn where she gets to her Zen place by tending a garden. “When I’m in the garden,” she says, “I don’t think. My internal narrator is shut off.”

And she’s had five-plus years to contend with another very famous Siri in the world, Apple’s personal assistant.

“My husband is convinced that someone at Apple read one of my books, thought I had a good name and promptly took it,” Hustvedt says with a laugh. “The change is interesting. I have carried this name for many years and people did not know that was a woman’s name. And no one knew how to spell Siri.

“When I’m feeling sort of chirpy about it I like to say, ‘I have a much better form of embodiment’ and sometimes when I’m annoyed I say, 'I’m the original.' "

Siri Hustvedt will be reading at Brookline Booksmith on Thursday, Jan. 5.