Advertisement

How Henryk Ross Risked His Life To Secretly Photograph Life In A Nazi Ghetto

"There was an order: 'All the Jews to the ghetto!' " Henryk Ross would later recall. "The Jews in the town were robbed. They carried the remains of their possessions into the [Lodz] ghetto."

Ross said this seated in a court witness stand in May 1961. He was dressed in a sport coat and button down shirt, open at the collar, testifying in his native Polish at the trial of the Nazi leader Adolf Eichmann, one of the hideous masterminds of the Holocaust. Ross was remembering back to the monstrous days at the beginning of 1940, recalling how he came, at age 30, to be imprisoned by the Nazis with hundreds of thousands of other Jews in the ghetto the Germans set up in the Polish city of Lodz. Prosecutors were using photos that Ross risked his life to secretly take there as part of the evidence that would help them convict Eichmann.

Hundreds of these grim black and white photos are now on view in the heartbreaking and horrifying exhibition “Memory Unearthed: The Lodz Ghetto Photographs of Henryk Ross” at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts through July 30. This photographic archive — including vintage prints as well as new prints from the original wartime negatives — is one of the largest and most complete records of life as a captive of the Nazis in the 1940s as recorded by one of their victims. (Search it here.)

“It’s very rare to have this archive intact and all of it together,” says Kristen Gresh, the MFA curator overseeing this presentation of the photos. (The exhibition was originally organized by Maia-Mari Sutnik for the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, which owns the collection.) It "helps us get a window into the life of the ghetto and the amazing sense of resilience and survival throughout this harrowing time."

“I did it knowing that if I were caught my family and I would be tortured and killed,” Ross himself wrote in 1987. But he was determined to create “some record of our tragedy, namely the total elimination of the Jews from Lodz by the Nazi executioners. I was anticipating the total destruction of Polish Jewry.”

Three Photographers

Henryk Ross had been a photojournalist for Polish newspapers before World War II began, then was part of the Polish army crushed between the Germans who invaded from the west on Sept. 1, 1939, and the Soviets who invaded from the east on Sept. 17. Poland fell within weeks.

The German Army entered Lodz on Sept. 8. By the time Nazi SS and Gestapo chief Heinrich Himmler visited the city (which the Germans renamed Litzmannstadt) on Oct. 28, Germans had restricted Jewish financial transactions, banned Jewish holidays, seized Jewish property, prohibited Jews from trading in leather and textiles, and rounded up many Jews for labor camps.

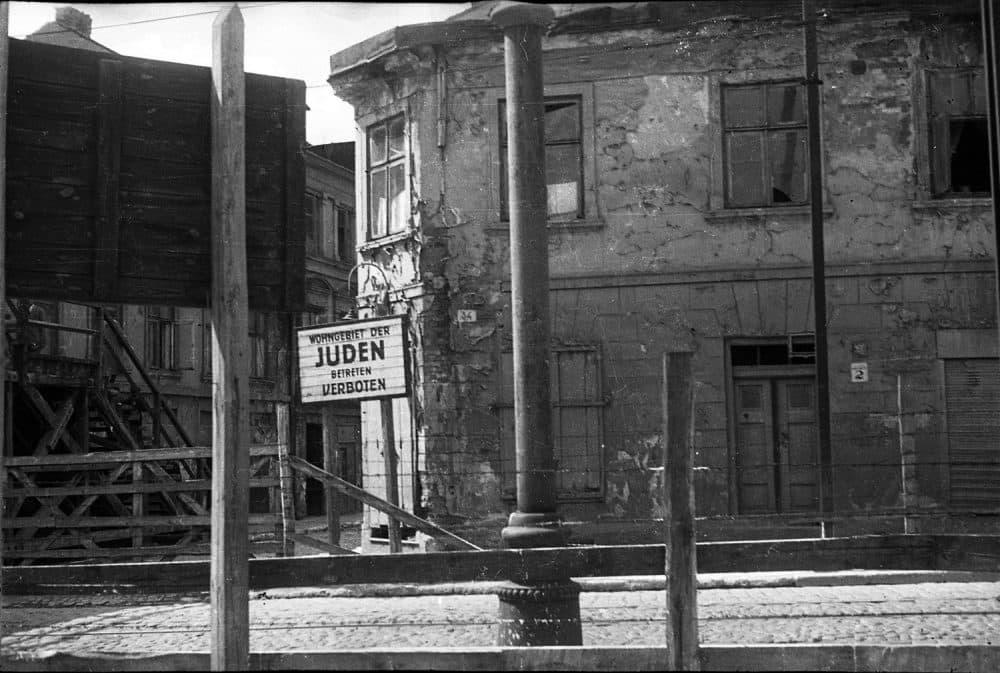

The Germans isolated the Lodz Ghetto from the rest of the city — and the world — turning it into a prison work camp. “Surrounding the ghetto was a fence guarded by Germans. In the beginning they were Volksdeutsche police in blue uniforms,” Ross testified. “Afterwards there were other guards on behalf of the German ruling power — amongst them men of the NSDAP [Nazi party].”

Jews were required to identify themselves by wearing the Star of David: “Even babies in their cradles were obliged to wear the badge on their right arm and on their back,” Ross said.

Gresh says the story is that when Ross arrived to be imprisoned at the Lodz Ghetto, his camera was confiscated, but then returned to him when he was given a photography job in the Statistics Department operated by the Jewish Council, or Judenrat. These were Jews within the ghetto who oversaw the community on behalf of the city's German Food and Economy Office, Ghetto Division.

The Statistics Department helped keep track of some 160,320 people held prisoner in the ghetto’s 4.13 square kilometers (it would later be reduced) by June 1940. Tens of thousands of Jews from the surrounding region and all of Western Europe were shipped into the ghetto. Thousands of Austrian Roma were segregated into a neighboring area. It was the Nazis’ second most populous concentration of Jews after Warsaw.

The MFA exhibit focuses solely on Ross’ work, but there was also another photographer in the Statistics Department busy documenting the ghetto. His name was Mendel Grossman. He was a 27-year-old aspiring painter, who’d taken up photography before the war — often retouching and conserving old family photos — to help support his family.

Grossman was now confined in the ghetto with his parents, two sisters, a brother-in-law and a young nephew in “one tiny room,” his friend Pinchas Shaar, a fine art painter who found work as a designer with the Statistics Department, said at a 1993 conference at New York’s Yeshiva University that was recorded in the 1999 book “Holocaust Chronicles.” “He was a small man, physically rather weak, with a severe asthmatic condition. Grossman spoke in short sentences, always a little skeptical, and often used the typically Lodzher Yiddish ‘Eh.’ He always carried a briefcase and wore an oversized raincoat that helped camouflage his Leica camera.”

The Statistics Department's official photographers took pictures of all residents for identification cards. Ross smiles in the photo stapled to his 1941 ghetto ID (included in the MFA exhibition). It shows him with his dark hair slicked back, a bristly mustache, but his cheeks are hollow, having lost the plumpness seen in his ID from three years earlier. By the end of his imprisonment, his weight would shrink to about 85 pounds.

The official photographers were also tasked to take portraits of ghetto leaders, document unidentified corpses on the streets, record changes to buildings as the Germans tore them down and take pictures highlighting the efficiency and productivity of ghetto workshops where Jews made textiles, leather shoes, mattresses (stuffing them with wood shavings) and uniforms for the German military.

Additionally, Ross photographed portraits of people on the streets and at home. He recorded happy times in the ghetto: parties, gardening, people cavorting in trees and meadows, couples kissing.

Ross and Grossman knew each other — but “we don’t know too much about their relationship,” Gresh says. Photographs attributed to Grossman show Ross photographing a group of people for identification cards. Ross photographed Grossman taking pictures of the excavation of a central cesspit in 1941, working on prints of German administrators, and photographing residents sorting through a pile of bags containing the belongings left by behind by the "deported."

There was at least one more person creating a photographic archive of the ghetto: Walter Genewein, chief accountant of the financial office of the German ghetto division for Lodz. The Austrian Nazi was lanky, in suits, with a thin mustache and his hair slicked straight back. In the Polish city outside the Jewish ghetto, he photographed German leaders comfortable in well-appointed offices and smiling next to handsome cars. He photographed a circus tent festooned with Nazi swastika banners. He also documented the ghetto.

Unlike Ross and Grossman’s black and white photos of the ghetto, which seem suffused with midnight anxiety, Genewein’s images are color slides filled with a chilly sunlight — revealing the reds, blues and greens of the dresses and sweaters worn by the women braiding yellow straw outdoors to make shoes or crowded around tables sewing inside a ghetto textile workshop. He photographed the rakes and chairs and washboards crafted in the ghetto carpenter’s shop. He photographed a visit to the ghetto by Himmler and German soldiers inspecting a ghetto textile storeroom. Using a camera reportedly confiscated from a Lodz Jew, Genewein apparently wanted to show the success of his efforts to help maximize the profitability of the Lodz workshops for the Germans.

Genewein’s color slides also show the yellow of the Star of David adorning ghetto prisoners’ clothes. He photographed smiling Jewish policemen arresting a stunned looking old man in the ghetto — an apparently staged shot. He photographed a German soldier guarding Lodz Ghetto Jews boarding a passenger train for deportation in April 1942.

At one point during the war, German leaders in Lodz contrived to create a museum of "Customs of Eastern European Jewry" and Genewein was tasked with planning displays, Frances Guerin reports in her 2011 book “Through Amateur Eyes: Film and Photography in Nazi Germany.” Germany’s central propaganda offices rejected the idea as too uncritical of Jews, she writes. They were apparently not convinced by the insistence of Hans Biebow, one of the German administrators of the Lodz Ghetto, that the museum was designed to “arouse disgust in anyone who comes in contact with” Jewish life.

‘To The Frying Pan’

“Our way is work!” was the slogan promoted by Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski, the Elder or top leader of the ghetto’s Jewish Council. He was seen by many as cruel and domineering, an accomplice to the Nazis' crimes. But his underlying strategy was apparently to make the ghetto community useful to the Germans — to give more people a better, longer chance at survival.

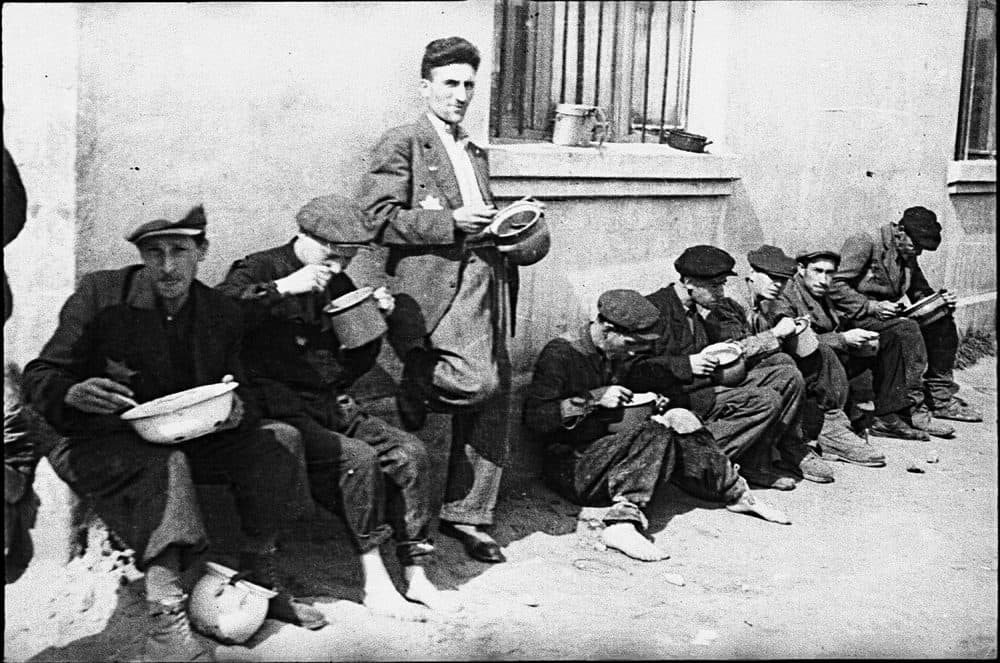

However, the Lodz Ghetto remained part of the Germans’ overall effort to kill Jews throughout Europe, and ghetto residents were dying. From overwork. From lack of food. From disease. “We received a loaf of bread for eight days. Apart from this there were food rations in small quantities, which were sometimes rotten. … Those who worked received an extra ration of soup,” Ross testified.

Jewish ghetto leaders buried rotten potatoes “in the ground in chlorine, as they were not suitable for use. The children knew where they were to be found and dug them up,” Ross said. “They were so hungry that it didn't matter to them what they ate.”

Ross said, “People either swelled up from hunger or became emaciated. There were cases of people collapsing in the street; there were cases where they collapsed at work and at home because of the difficult conditions. We were six to eight persons to one room, depending on the size of the room. People froze from the cold. There was no heating. … I saw entire families, skeletons of people, who during the night were dying with their children.”

Grossman photographed the decline of his own family — his parents and brother-in-law succumbing in 1942 and his young nephew Yankel dying of hunger in 1943.

In 1941, the Nazis set up a facility at Chelmno nad Nerem, about 30 miles northwest of Lodz. Prisoners were shipped there, sealed into the rear compartments of “gas vans,” and murdered by pumping in the vehicles’ poisonous exhaust fumes. Their bodies were then buried or burned.

In the first half of 1942, some 52,304 Jews from Lodz were herded onto freight trains at Radogoszcz station and sent to their deaths at Chelmno, joining some 4,500 Roma who’d been sent ahead of them.

“In the year 1940, it was still not known [where the transports were going to],” Ross testified, “but in 1941, at the time of the further deportations, the Jews began to make inquiries and it became known to them that they were going into the ‘frying pan.’ … This was a routine expression of the people in the ghetto. They knew they were going to be burned, they used to call this ‘going to the frying pan.’ ”

‘Forbidden’ Photos

“When I had more free time,” Ross told the Israeli court, “I also used to take photographs which it was forbidden to take.”

Grossman took illegal photos too. Exhibition organizers are unclear whether the two men knew they were both working on assembling a secret record of Nazi crimes. Ross recorded official ID portraits by photographing large groups all in a single frame, then cropping the negative to print individual portraits — apparently in an effort to stockpile film for unofficial use. But this cannot account for all the seemingly unofficial photos Ross and Grossman took. Perhaps Jews in charge of the film and printing paper purposely turned a blind eye to the supplies the men were using up.

A late 1941 order severely restricted their photography. Rumkowski wrote to Grossman that Dec. 8: “I inform you herewith that you are not allowed to work in your profession for private purposes. ... Your photographic work is confined only to the activity in the department in which you are employed.”

“To fool the police, [Grossman] carried his camera under his coat. He kept his hands in his pockets, which were cut open inside, and he thus could manipulate the camera. He directed the lens by turning his body in the direction he wanted, then slightly parted his coat, and clicked the shutter,” Arieh Ben-Menahem, a photographer who worked as Grossman’s assistant during the war, wrote in the 1977 book “With a Camera in the Ghetto: Mendel Grossman.”

Ross adopted a similar technique. Stefania Schoenberg — whom he married under a chuppah (canopy) in the ghetto in 1941 — sometimes served as his lookout. The photographers were helped in keeping low profiles by using the small, lightweight, hand-held cameras that had begun to revolutionize photography by replacing heavier, bulkier cameras and tripods in the 1930s.

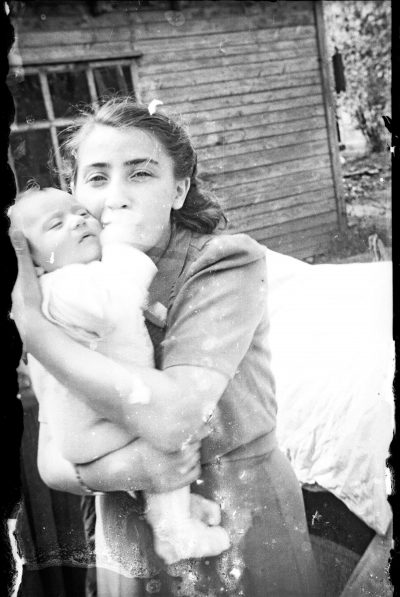

It’s difficult to tell from the Ross and Grossman photos that survive exactly which were on-the-job pictures and which were secret, illegal photos. (Also over the years, publications have repeatedly misidentified and confused Ross’ and Grossman’s photos, so attribution can be tricky.) Ross photographed the smashed ruins of the Wolborska Street synagogue after the Germans demolished it in 1939 — and a man carrying the Torah he saved from the rubble. Grossman and Ross photographed people moving into the ghetto, carrying their possessions on wagons or dragged on crude sledges. They both photographed the barbed wire caging in the ghetto. Ross took tender photos of a woman hugging and kissing her infant and being hugged by (apparently) her husband, a policeman for the ghetto’s Jewish authority.

Grossman and Ross both surreptitiously photographed hangings. Grossman “climbed electric power posts to photograph a convoy of deportees on their way to the trains, he walked roofs, climbed the steeple of a church that remained within the confines of the ghetto in order to photograph a change of guard at the barbed-wire fence,” Ben-Menahem wrote.

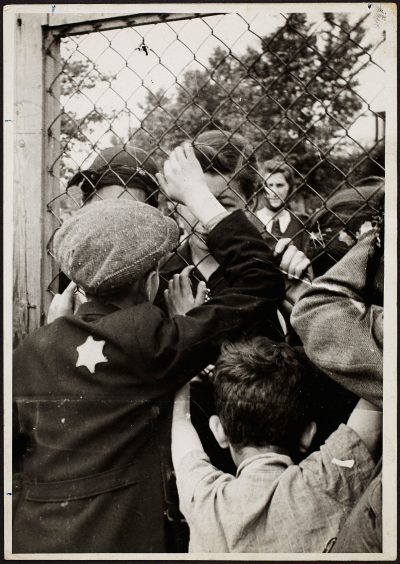

Ross photographed people protesting at the kitchen because of lousy food. He photographed a man collapsed in the street from hunger. Grossman photographed people kissing goodbye during deportations. Ross recorded a little boy dressed as a Jewish policeman “arresting” a playmate. He photographed two boys seeming to speak to a woman on the wrong side of a chain-link fence. “The mother of these two children was deported and the children stayed behind in the ghetto. They were deported later on, but not together,” Ross recalled in David Perlov’s 1979 documentary film “Memories of the Eichmann Trial” (screening in the first room of the MFA exhibit).

“At moments when no German was seen in the vicinity, when they had gone elsewhere to beat up people,” Ross testified at the trial, “I took advantage of that moment to take photographs.”

‘They Snatched Children’

In late August 1942, the Germans decided to eliminate all who could not work from the ghetto — the sick, the children, the elderly — except from the families of ghetto officials and police. “Rumkowski had not been willing to split up families,” Holocaust scholar Robert Jan van Pelt reports in the exhibition catalog. But on Sept. 1, Rumkowski ordered Jewish police to seize patients from hospitals and take them to the trains. On Sept. 4, Rumkowski gave a public speech to parents in the ghetto imploring them to give up their children for "resettlement."

According to “The Chronicle of the Lodz Ghetto,” a daily diary of the community authored by multiple members of the Jewish administration, Jewish police and firemen surrounded buildings, Nazi Gestapo ordered people out, and Jewish police searched inside to round up any stragglers.

Ross seems to have been talking about this period when he testified: “They … snatched children from the arms of their mothers; I do not have to say that this was not voluntary, and I do not see the necessity for talking here about the shouts and the blows.”

People who tried to escape were shot dead on the spot. Ben-Menahem writes that Grossman insinuated himself among a group of gravediggers to photograph victims piled in the cemetery.

“I saw an instance where they collected children in a particular hospital in Drewnowska Street,” Ross said. “The Germans concluded that too few people were riding in the vehicles. They said they had to load more. The trucks came to the front of the hospital where the children were assembled. … The children scratched the walls with their fingernails. The children did not cry any more, they knew what awaited them, they had heard about it. They could not cry. The Germans were running around in these rooms, they beat them and threw them from the windows and the balconies into these trucks. I was not there for a long time, for it was dangerous even for me to be there.”

Ross photographed Jewish police — with their distinctive Star of David armbands and round-sided, flat-topped hats — at a hospital window helping take people for “deportation.” Ross photographed horses clopping down the ghetto’s cobblestone streets pulling wooden wagons overflowing with children, never to return.

By Sept. 12, historians believe some 15,681 people — including 5,862 children — were shipped out of the ghetto and murdered at Chelmno. By late 1942, the ghetto population has been reduced to 89,446 residents.

‘Through A Hole In A Board’

The grueling forced labor in the ghetto workshops continued until June 10, 1944, when Nazi leader Heinrich Himmler ordered the extermination of the Lodz Ghetto. At that point it was the longest surviving Nazi ghetto in Poland — the Germans had eliminated the Warsaw Ghetto a year earlier. Between June 23 and July 17, 1944, some 7,196 Lodz Ghetto residents were sent on the last transports to Chelmno. In August 1944, about 70,000 more residents were put on trains out of Lodz to the Auschwitz death camp.

Ross secretly photographed a crowd of Lodz Jews being ushered onto a train of boxcars: “People with whom I was acquainted worked at the railway station of Radogoszcz, which was outside the ghetto but linked to it, and where trains destined for Auschwitz were standing. On one occasion I managed to get into the railway station in the guise of a cleaner. My friends shut me into a cement storeroom. I was there from six in the morning until seven in the evening, until the Germans went away and the transport departed. I watched as the transport left. I heard shouts. I saw the beatings. I saw how they were shooting at them, how they were murdering them, those who refused. Through a hole in a board of the wall of the storeroom I took several pictures.”

Ross’ photo is blurry, taken from a distance, behind what seems to be a line of concrete slabs. No German soldiers are in sight, just the Jewish police of the ghetto, with their Star of David armbands, standing at the edge of the crowd and perched in the door of a boxcar helping a woman climb aboard.

Ross’ photos of Jews apparently collaborating in the execution of their neighbors as well as his pictures of happy times in the ghetto have long been controversial. “Basically the ghetto was run by Jewish officers who were forced to implement Nazi wishes,” Gresh says. “That’s part of the complexity of the Jewish Council.” Ross and Grossman, of course, were a part of the Council too. “They were all actually victims because so many in the ghetto did die, but in everyday life there were different levels.”

Grossman’s sister Fajda and the Jewish leader Rumkowski were among the Lodz Jews then taken to Auschwitz, where they perished. Most were sent directly to their deaths in the gas chambers.

Hiding The Photos

Ross and Grossman managed to survive until the Nazis launched the final 1944 elimination of the Lodz Ghetto — perhaps in part because their special status as employees of the Jewish Council had helped protect them. As the end of the ghetto arrived, they hurried to preserve their photographic evidence of Nazi crimes.

“I hid the [about 6,000] negatives in barrels and concealed them in the ground,” Ross testified. “I hid them … in the presence of several of my friends, so that if we died and one of us survived, the photographs would remain for the sake of history.”

Grossman’s friend, the designer Pinchas Shaar, said the photographer stashed thousands of negatives, hundreds of prints, his Leica camera and jewelry entrusted to him by relatives in two big clay jars and buried them in opposite walls of an abandoned bunker. Ben-Menahem gives a somewhat different account, writing that Grossman packed his archive in tin cans inside a wooden crate, “with the help of a friend he took out a window sill in his apartment, removed some bricks, placed the crate in the hollow, then replaced the sill.” The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., says the prints were hidden in the apartment and in a cellar.

In fall 1944, Grossman was sent from Lodz to a concentration camp in Germany, about 20 miles southwest of Berlin. Shaar said he was there with Grossman as Soviet forces surrounded Berlin in April 1945 and the SS camp commander tried to hurry the Jews out of the facility. Shaar said Grossman was marched out in a first group, but the rest of the prisoners were halted when American and British bombers flew over and were liberated days later by Soviet troops. Among these soldiers, Shaar recalled, was a Jewish commander: “He said we were the first living Jews he had encountered on the march from Moscow to Berlin.”

“After the war, upon meeting the survivors of the first group [marched out of the camp], in which Grossman had been included, we learned that they had been taken in the direction of the Bavarian Alps,” Shaar said. “Sick men on the march who could not keep up with the group and lagged behind were shot. One of them was Mendel Grossman.”

‘Fortunately I Remained Alive’

After nearly all the prisoners had been shipped out of the Lodz Ghetto, the Germans still left about 900 people behind as a final “clean-up crew.” They were tasked with emptying the ghetto buildings, gathering anything useful, searching for any valuables the departed may have hidden. Ross and his wife were among these people — whom the Germans planned to kill after they finished the work.

Ross continued to photograph. Apparently during this time, he recorded baskets and metal pails collected into a pile in an abandoned street amidst the ghost town of empty houses.

The Russian Red Army liberated the ghetto in mid January 1945. Ross and his wife were among the 877 recorded as survivors there. He photographed some of the celebration — including what looks like a woman dancing with a smiling Soviet soldier. He photographed a half a dozen freed Lodz Jews standing under the sign reading “Residential Area of the Jews / Entry Forbidden” above the now open gate to the ghetto. They seem wary, but grin.

In March 1945, men and women, a boy, gathered to help Ross dig up his archive from a patch of earth near his ghetto home, with a tree at the edge, some brambles, and a building in the distance. A photo shows him stooping over to lift out the box as the group smiles.

“Fortunately I remained alive and I dug them up,” Ross testified. “Some [of the negatives] were destroyed owing to water seeping in, but the greater part was saved.” In fact, about half were lost. Many of those that survived were damaged (which the new prints in the MFA show purposefully reveal, like scars).

“It’s a reminder of all that the camera can be,” Gresh says. “It can be a weapon and it can be an act of resistance.”

After the final German surrender that spring, Shaar said, he returned to Lodz on foot. “The first thing that I and my brothers did was … excavate [Grossman’s] hidden jars.” Part of the photo archive was missing, he said, but prints and hundreds of negatives remained. Grossman’s younger sister, Ruzhka (sometimes spelled Rozka) also found her way back to Lodz and took or sent the negatives to the Kibbutz Nitzanim in Palestine. But when Egyptian forces overran the kibbutz and took residents captive during the 1948-’49 Israeli War of Independence, Ben-Menahem wrote, “the treasure was lost.” All that is known to survive of Grossman’s project are prints that remained in the hands of friends.

Genewein, the Nazi accountant and photographer in Lodz, survived the war and returned to his native Austria. In 1947, a neighbor reportedly accused him of having enriched himself with a valuable rug and vase taken from Jews. He spent a month in jail, but managed to explain the accusation away without facing formal charges. He died in 1974 at the age of 73. His cache of Lodz ghetto photos only became known publicly when some 400 of his color slides from the 1940s turned up in 1987 in a Vienna antique shop.

Ross lived to 1991. After the war, the MFA exhibition reports, he operated a photography business in Lodz and photographed the trial of Hans Biebow, one of the German administrators of the ghetto, in a Polish court at Lodz in 1947. In the 1950s, Ross moved with his family to Israel. In 1961, when Ross testified at the Eichmann trial (Eichmann “kept looking at me as if he was angry I survived,” Ross’ wife Stefania says in “Memories of the Eichmann Trial"), he was working at Orit Zincography — apparently a lithographic printing business — in Tel Aviv.

Ross published a collection of his photos, “The Last Journey of the Jews of Lodz,” the following year. He seems to have given up on documentary photography as a profession. But for decades, he edited and re-edited a 17-page photographic folio (included in the exhibition) of his years in the ghetto.

“These four years,” Gresh says, “were truly his life’s work.”