Advertisement

REVIEW

Warily Watching The Years Pile Up In Richard Russo's 'Trajectory'

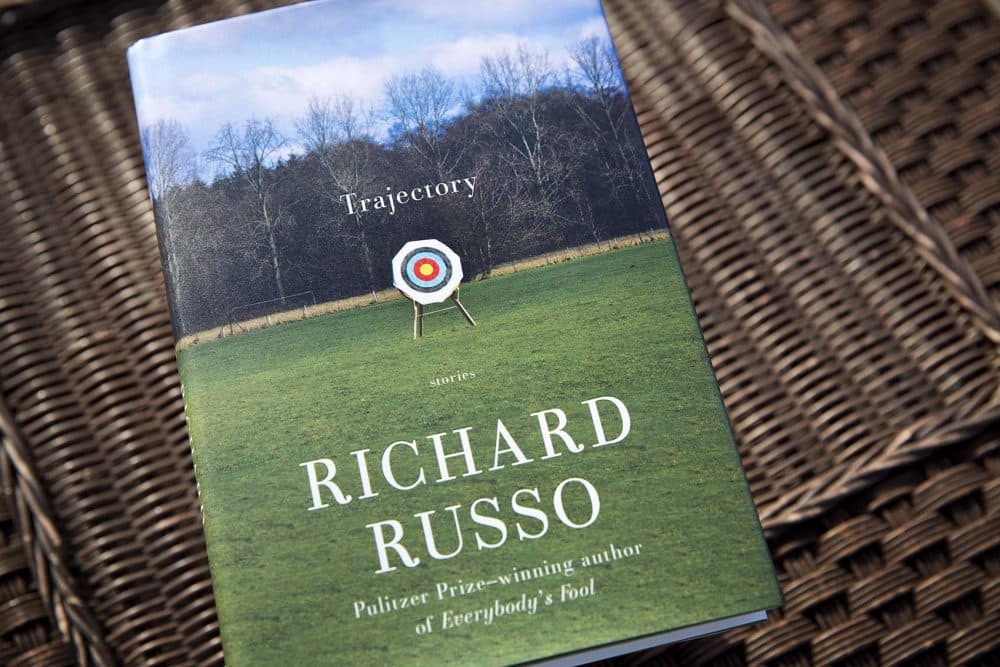

If there’s a visual metaphor that thematically encapsulates Richard Russo’s new collection of short stories it may be the one right on the book jacket. It’s an archery target sitting in a wide-open field. As metaphors go, yes, it’s broad, especially given that it perches beneath the book’s title, “Trajectory.” But in the hands of an expert storyteller like Russo, that’s not a concern, since the characters in these four stories are in the kind of fixes he's presented to readers in book after book: regular folks who aren’t sure why they continue to get the short end of the stick.

This collection is a bit different from the rest of Russo’s oeuvre. Instead of the upstate New Yorkers he usually writes about, he turns to his adopted home of New England and gives us a couple of lost-at-sea faculty members: a Maine realtor and a novelist with a side job as a screenwriter. A line in one of the stories applies to the entire lot: “They were human, and there’s no app for that.”

The main protagonists in these stories are warily watching the years pile up; some are dealing with health issues of their own or of their loved ones. Reading about these travails I was reminded of what Philip Roth said about old age: “It’s not a war, it’s a massacre.” Russo’s characters in “Trajectory” are not yet fighting that battle, but would surely tell you that middle age amounts to, if not a battle, at the very least, a nervous look over the ramparts.

Asked about his new book Russo, 67, a Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist and a resident of Camden, Maine, told an interviewer: “It’s all stories about the trajectory of people’s lives. A lot of them are middle-aged or older people who look at their lives and think to themselves, ‘How did I get here?’ Who were they when they were young and what decisions did they make that brought them to this particular place in time where they are questioning everything?”

In “Trajectory” this lack of an existential GPS doesn’t always form itself into such questions, but these characters still turn to the past for answers. However, mostly they are simply struggling to “keep it between the ditches,” as Steve Earle would say. Or, as Russo generalizes: “People cling to folly as if it were their most prized possession, defending it, sometimes with violence, against the possibility of wisdom.” Such life-isms are sprinkled throughout the pages of “Trajectory.”

First up is “Horseman,” in which a professor’s nabbing of a plagiarizing slacker sends her back a decade to confront her own moment of truth in the office of her graduate adviser. When the esteemed professor tells Janet Moore that on the page she has all the right moves but that there’s no “there there,” she’s thrown for a loop. “It’s as if you don’t exist,” the adviser tells her. He could never know how right he is. A decade later, Janet, married to an unambitious man and raising a distant and mentally challenged son, has not found anything galvanizing in literature -- only a place to hide.

She recalls someone writing the word “effaced,” and wonders if that’s what happened to her. The word made me think of Marshall McLuhan’s notion about the self-effacement he believed transpired when one viewed Renaissance art: “The viewer… is systematically placed outside the frame of experience.” In the same way, Janet has been a mere spectator of her own life, outside its frame.

This is also true of Nate, the protagonist in the book’s second story, “Voice.” He's another faculty member, a retired English professor smitten with Jane Austen novels. Despite the injustices Russo heaps on him, we readers can see he is not the loser he’s lived his life as. But in the shadow of his older brother, Julian, a salesman, Nate never seems to measure up, for Julian has always possessed a “lifelong ability to reduce Nate to a welcome state of insignificance.” Nate has found things easier on the sidelines of his own life. His present is intertwined with memories of how he was recently accused of mishandling a brilliant but troubled and mute student. Where the school saw inappropriate behavior, readers see the outreach of a caring but desperate man.

These stories are not so much plot-driven, but situational. Russo’s not so much concerned with narrative drive as with creating characters you care about or are at least endlessly curious about. As to cluing us in about how they ended up where they are, memory rears its defiant head in each of the four stories, showing us how the trajectory of these lives was formed. The lead characters flash back and forth in time between the present and often unsettling past experiences. How the characters are shaped by these incidents or react against them provides part of the stories’ drama.

These stories are not so much plot-driven, but situational. Russo’s not so much concerned with narrative drive as with creating characters you care about or are at least endlessly curious about.

If our two faculty members finally claw their way to epiphanies, the protagonist of “Intervention” has more at stake than a life crisis. Ray, a realtor in Maine, has cancer, as well as a decision to make. In a funny life-ism, Russo tells us that Ray has been married to Paula for 30 years, keeping things together “in large part to a mutual willingness to let an arched eyebrow do the heavy lifting of a soliloquy.”

Surrounded in life and in memory by friends and family members who range from fast-talking hucksters to a father who traded risk for safety, working at a mill and taking only what life handed him. His current situation is complicated by a recently widowed woman who’s trying to sell her house, and would, but for the boxes of memories clogging every room and scaring off potential buyers. The detritus of her life works as a metaphor for the clutter Ray needs to sort through to get what he needs to ensure this "long Maine winter" is not his last.

Cancer plays a role in the last story of the collection called “Milton and Marcus,” this time taking a toll on the protagonist’s wife. Told in the first person, our novelist cum screenwriter is beckoned by a Jack Nicholson-like film star and his producers to bring to life a decade-old treatment for a buddy movie. Russo, who’s had his own brushes with Hollywood, seems to draw on his experience, and begins the story with some Mamet-like reflections on the industry, such as, “In the film business you hate for things to be [expletive] up at the start. They’ll end up there, it goes without saying.” Our writer is wined and dined, smiled at, lied to, and ultimately sent home with a pat on the butt. Naturally, he can’t wait to finish the screenplay and get back in the game. “My point is that even though the whole charade is pretty tawdry and transparent, you look forward to it, or part of you does, the part that enjoys being flattered and lied to.”

This story contains the collection’s biggest failing. The wife’s cancer in “Milton and Marcus” seems tacked on to give the tale a touch of drama and gravitas. This becomes apparent as Russo tries to draw the story to a close and wring something higher from the proceedings. I was waiting for the frisson of connection or meaning, something that, seen from the end of the tale, could provide the poignant takeaway, or a life-ism writ large. Evidently, Russo was waiting for it too. The fact that it doesn’t arrive doesn’t mean the story isn’t a hell of a lot of fun, and a demonstration of how good a scene-crafting screenwriter the author is. But the final paragraphs, though beautifully written, feel like the breeze from a two-strike swing.

Elsewhere in “Trajectory” however, Russo triumphs in ways big and small, and has crafted another winning collection.