Advertisement

Review

Andy Warhol Meets Norman Rockwell In The Berkshires — Not Such Strange Bedfellows?

Andy Warhol and Norman Rockwell. Together again.

If pairing these two opposites seems like a gimmick, the Norman Rockwell Museum soon disabuses you of the notion. “Inventing America: Rockwell and Warhol” asks fascinating questions about the two men, the art world and even American history.

Here you have two artists who so neatly symbolized adjoining decades. (And whether the two were really “artists” at all hangs in the air at the Stockbridge museum, too, even if unintentionally.) Think of Norman Rockwell and you think of the ‘50s — the family values of sitcoms like “Leave It to Beaver,” the grandfatherly presidency of Dwight Eisenhower, the safety net of people in small towns looking out for each other — though Rockwell was edgier than his image. (One of the reasons he lived in Stockbridge was because it was home to therapists for him and his wife.)

Think Andy Warhol and you think of the sex-drugs-and-rock-‘n’-roll ‘60s — JFK, the Stones, anti-war protests, hallucinogenic paintings — even if Warhol himself was more conservative than his image.

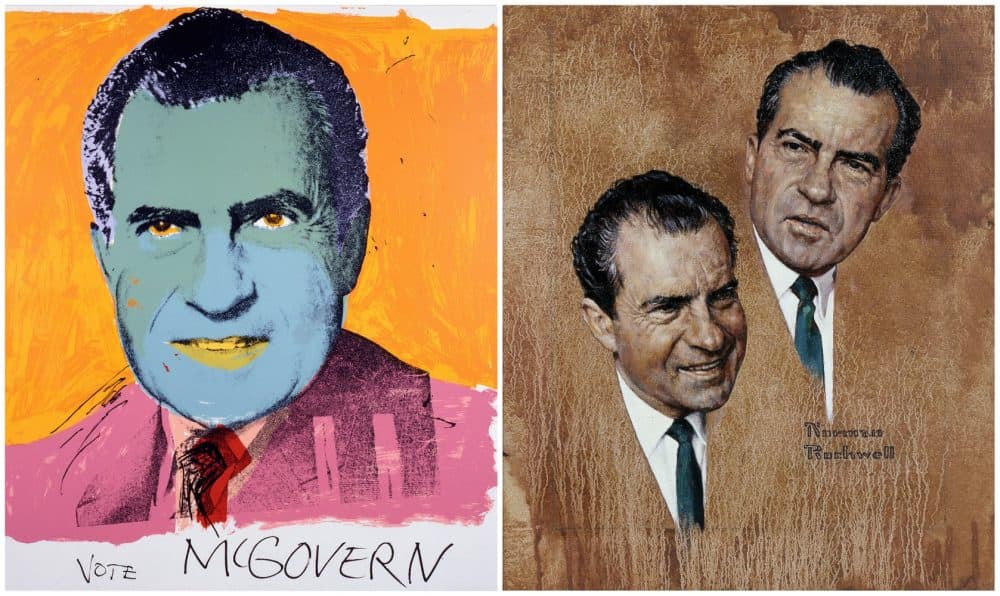

Yet the exhibit (through Oct. 29) pops not only when it shows how the two were different, but how the two were similar. Look no further than their portraits of Richard Nixon for the differences. Warhol paints him as a vampire, a sickly blue face with yellow lips, in “Vote McGovern.” Rockwell gives him a hair transplant and a face-lift, slimming down his cheeks. The museum notes that this didn’t mean he was a fan of Nixon; Rockwell thought that his politics shouldn’t enter into the painting.

That would be enough to disqualify Rockwell as an artist in the eyes of many. What is an artist without a point of view? A journalist or an illustrator, perhaps, which is how Rockwell saw himself, humbly stating that he didn’t think he was an artist, either. He's quoted in the exhibit saying, "I have a misguided art dealer [at the Danenberg Gallery] who thinks I am an artist."

But Warhol did consider Rockwell to be an artist. He owned a couple of Rockwell's paintings and thought that he was a precursor of hyperrealism, a movement that started in the 1970s, featuring artwork resembling hi-resolution photos.

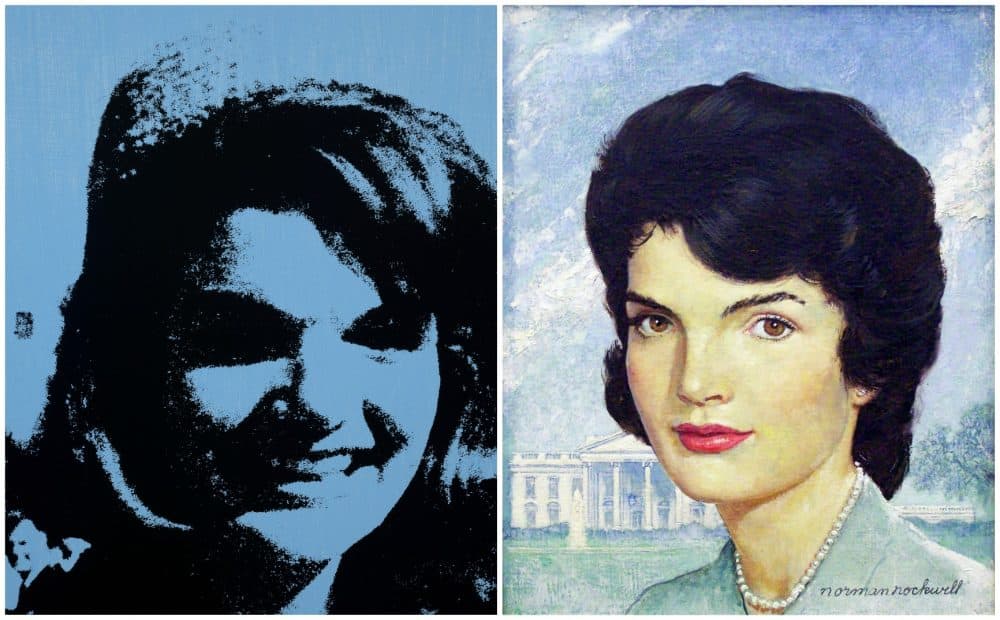

One of the Rockwell paintings that Warhol bought was "Portrait of Jacqueline Kennedy." When Rockwell painted her, she was the debutante turned First Lady, a woman who exuded poise and class, the face of a nation’s optimism. For Warhol, she became the face of something much darker in the American psyche — though Warhol was attracted to celebrity even more than Rockwell was.

Warhol hobnobbed with rock stars, but if Rockwell didn't share a joint with Al Kooper and Mike Bloomfield, he painted a memorable album cover of the two.

And both loved to paint the everyday props of Americana, from Campbell’s Soup cans to Thanksgiving turkeys. As with almost everything they painted, of course, Warhol’s world view was steeped in irony, Rockwell’s in idealized tribute. And ultimately, Warhol took the art world to new places; Rockwell did not.

What does it say that Rockwell captured the popular imagination more than Warhol did? Despite their mutual attraction to artistic populism, it doesn’t say much. If it did, as my old college professor James Riddell used to say, we’d have to consider Rod McKuen a greater poet than T.S. Eliot. There are still critics who wholeheartedly dismiss both men as trivial pursuers, though Warhol, at least, has standing among most visual art writers.

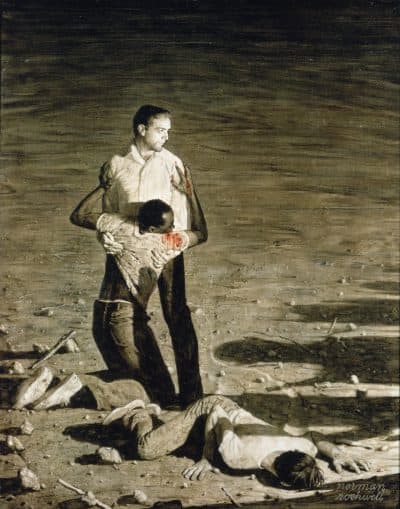

Still, who’s to say that Rockwell’s idealized vision of American exceptionalism is less worthy of artistic attention than Warhol’s jokier take on what makes us tick? They were also fully capable of escaping their fantasies and taking the world head-on, as their civil rights artwork at the top of the post shows.

In the end, I find a little of both artists goes a long way. But the museum’s inspired pairing of the two is a fascinating reminder that the aesthetic issues they both raise are worthy of respect and appreciation.