Advertisement

Review

From Picasso To Rauschenberg, Williamstown Museums Embrace The Modern World

By now it shouldn’t come as any surprise that MASS MoCA isn’t the only place in the Berkshires to hunt for 20th and 21st century art. The Williams College Museum of Art has always had an eye on contemporary art in its contained but powerful collection.

But the Clark Art Institute has also marched boldly into the post-19th century world. It’s no longer just the appointment museum in the Northern Berkshires for its astounding collection of Monets and Manets; Homers and Turners.

While a lot of the talk in Western Mass. revolves around the Berkshire Museum’s witless decision to sell 40 paintings to help fund a renovation, other museums are stepping up their game.

Among the Clark exhibits now are “Picasso: Encounters” and two exhibits by the abstract expressionist Helen Frankenthaler. And down the road at Williams' museum sits one of the progenitors of pop art, Robert Rauschenberg, and the photo-like symbolism of Meleko Mokgosi. (And even the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge has inventively paired Rockwell with someone more readily associated with modern movements, Andy Warhol.)

Pablo Picasso: "Encounters"

None of these exhibits is overwhelming in terms of quantity. “Encounters” (through Aug. 27) centers on Picasso’s prints and his collaborations with others, either his models/muses/lovers or printmakers and other artists like Georges Braque — the two are credited with co-inventing cubism.

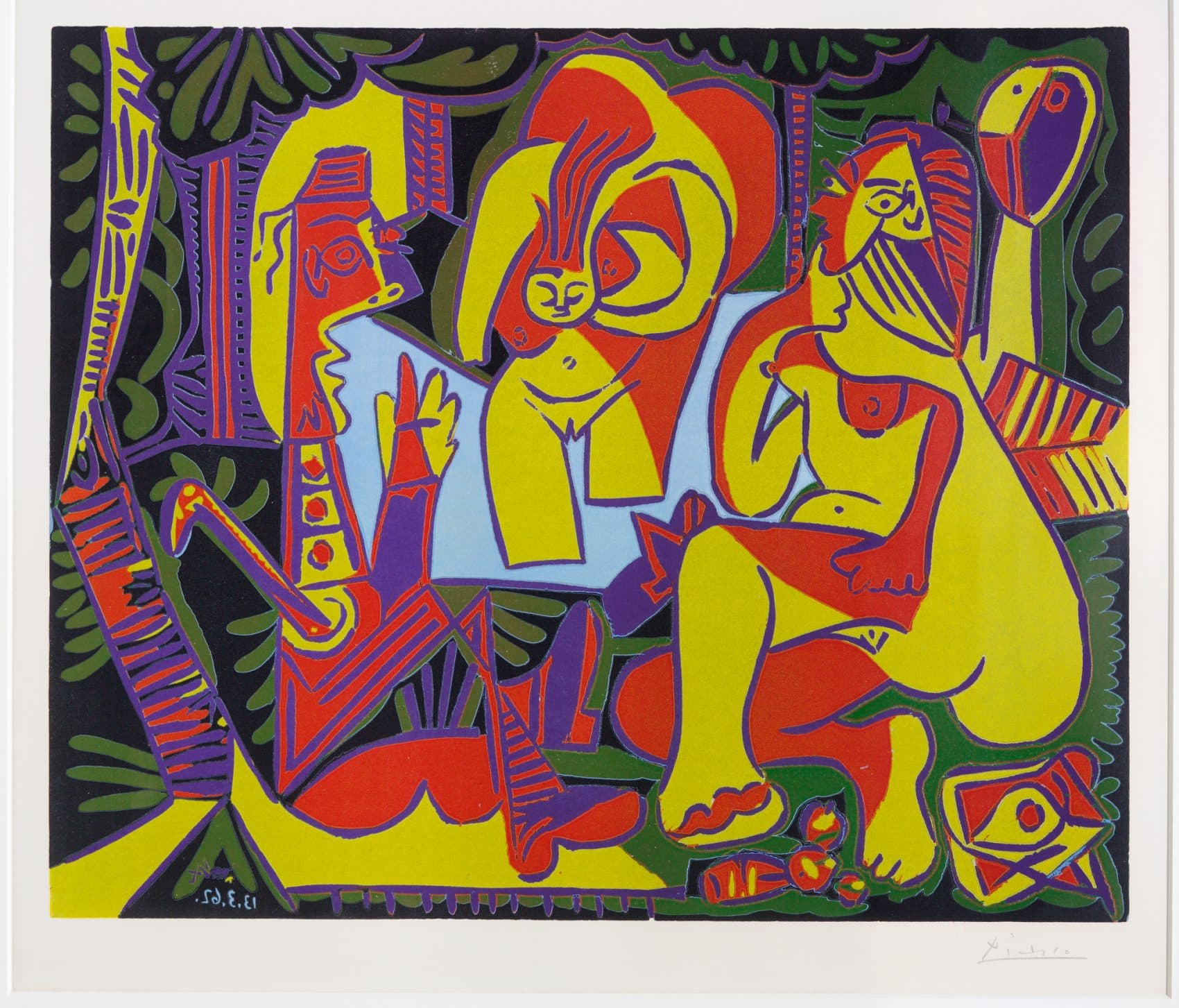

The Clark’s aim seems to be to dent the myth of the artist working alone, touched only by divine guidance and answerable to no one. That isn’t the case, the exhibit demonstrates. Eugène Delâtre, for example, added his own touches to Picasso’s gripping early starving-artist print, “The Frugal Repast.” Picasso's "Luncheon on the Grass (After Manet)" and "Still Life with Glass Under the Lamp" were printed by Hidalgo Arnéra, with whom he collaborated for eight years.

What interested me more, though, was how the exhibit highlights his work with his many wives and lovers. I’ve seen shows that leave you thinking that not only was Picasso a misogynist but maybe a borderline psychopath in the ways he cut up women and reassembled them unflatteringly.

The Picasso here is kinder and gentler — though anything but a sensitive New Age guy. Still, whether one wants to judge him by his romances or not, there is a lovingness and tenderness at work in the prints and paintings here, as in his "Portrait of Dora Maar," with descriptive wall notes that highlight the accomplishments of his models. (Maar was a surrealist photographer.) It’s a welcome, and unexpected, glimpse into Picasso as human being rather than misogynist myth.

Helen Frankenthaler: "As In Nature" and "No Rules"

One of the great aspects of the Clark’s redesign of 2014 is how its buildings now open up onto the lush Berkshires landscape, so mounting “As in Nature,” a collection of Helen Frankenthaler’s mostly large-scale paintings (through Oct. 9) in the Lunder Center atop Stone Hill — a hearty, worthwhile walk up from the main building — is a natural. (There’s also a shuttle.)

Frankenthaler, it’s noted, was a leading abstract expressionist, but there are glimpses of representation. You might not think, at first, that there’s much of a connection between what she’s painting and the world you see outside designer Tadao Ando’s windows — Mount Greylock, the Taconics, the Green Mountains — but the longer you spend there, the more one informs the other.

There are rough edges in the beauty of both; there’s color and purity. And a connection to what came before. Take a look at Turner’s “Rockets and Blue Lights” in the Manton Collection of British Art either before or after visiting Frankenthaler and then compare it to her “Barometer, 1992.” You can almost see Moby Dick coming out of the seeming tranquility of the whiteness.

There’s also an exhibit of her explosive woodcuts in “No Rules” at the Manton Research Center. (I would have voted to integrate the British collection with the American and European 19th century works in the main building.)

Robert Rauschenberg: "Autobiography"

It can sometimes seem as if MASS MoCA had been built for the large-scale artful mash-ups that Rauschenberg reveled in. But while he’s the perfect guest at North Adams, Williams College actually has a course built around his work. When the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation made the artist’s archives available to scholars and MASS MoCA included the exhibit, “A Quake in Paradise (Labyrinth),” in its expansion, this seemed to be the perfect time for a public exhibit of their own at the Williams College Museum of Art (through Aug. 20).

The art history/museum course investigates the relationship of Rauschenberg’s life and work, making “Autobiography” the perfect complement to the class. “Autobiography” is actually his three-part work, 4½ by 17 feet, that includes photographs, Rauschenberg’s horoscope and photo-reproductions of an X-ray of his body.

The 26-work exhibit (through Aug. 20) also includes a video and stills of “Pelican,” his 1963 choreographed performance, photos from his Black Mountain College self-portraits and his collaborations with the Talking Heads centered on their album, “Speaking in Tongues.”

I have to say I’ve always been a bit underwhelmed by Rauschenberg, or at least unmoved. His work is more likely to elicit an “Oh, that’s interesting” than any sense that his art opens a fascinating new window on the world. I know, he brings the everyday world into tow with the art world, and he was an enormously influential figure in 20th century art. And, formalistically, one could write volumes about his processes.

All of which I find endlessly, well, interesting.

Meleko Mokgosi: "Democratic Intuition"

I have no such reservations about the Botswana-born, Williams-educated Meleko Mokgosi’s “Democratic Intuition” series (through Sept. 17) which mixes hyper-realistic representation with psychoanalytic symbolism and post-colonial aesthetic theory.

If that sounds like a mouthful, Mokgosi’s cinematic artwork is as direct as it is abstract. You might have to provide your own storyline at first, but his figures jump off the WCMA walls whether celebrating everyday life and love or confronting power structures, both political and psychological, in southern Africa.

That said, there is still plenty of room for interpretation. Is the man in the far-right panel (above) sitting in his beautifully appointed living room thinking of the nude woman as another of his possessions? Is she real, a statue, a figure of his subconscious? Is his daughter looking at him in reproach or wonderment? The more you look at Mokgosi’s art, the richer the narrative becomes.

MASS MoCA has made North Adams a must-stop in the Berkshires for lovers of 20th and 21st century art. You can now say that the Clark and the Williams museum have done the same for Williamstown.