Advertisement

Mercurial, Vicious, Brilliant — Uncovering The Real Lou Reed

No rocker explored the dark underbelly of his own psyche — or ours — as did Lou Reed. And few made it so hard for fans, rock critics and biographers to answer the question: Who was the real Lou Reed?

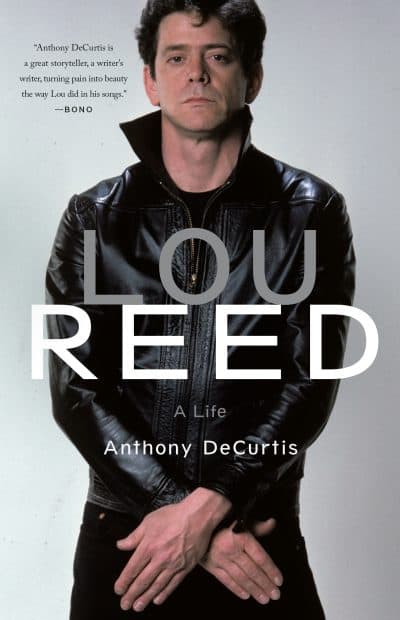

It’s what his most recent biographer Anthony DeCurtis strives to address in "Lou Reed: A Life," a 500-plus page book, out Tuesday, Oct. 10, and it’s one I’ve wrestled with over several decades.

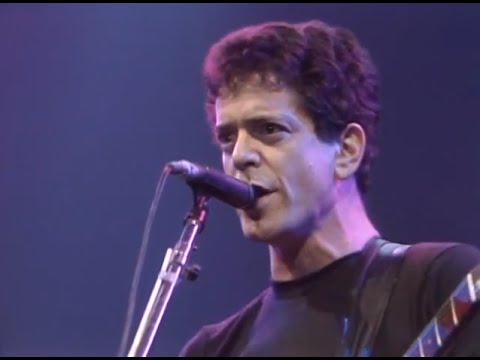

Reed was witty, vicious, contradictory and brilliant, both in song and in real life. He could be terse; he could be loquacious. The darker, more harrowing songs are what people tend to associate with the late New York singer-songwriter-guitarist. Yet, Reed was capable of crafting songs that were pure, transcendent joy, both with the Velvet Underground and later as a solo artist from 1972 to 2011.

When he set out to write the biography about three years ago, DeCurtis said he had one primary goal: “To get at his complexity. I was hearing a lot of the negative stuff, but he was a genius as far as I’m concerned and there was also an incredible sweetness to him. I wanted to paint a portrait, I felt that in some of the other biographies, there’s a cartoon Lou Reed — a monster — and I wanted, to the degree that I could, to erase that.”

There have been at least four other Reed biographies, but DeCurtis, a Rolling Stone contributing editor and creative writing professor at the University of Pennsylvania, says he took the approach of writing a “critical biography. This views the life and the work on equal terms. It’s meant to find things in life that reveal things about the work and find things in the work that reveal things about the life.”

Reed once told Rolling Stone's Mikal Gilmore that his 1978 double-live album, "Take No Prisoners" — with Reed acting as an acerbic standup comic segueing into loose, jazzy re-arrangements of his classic tunes — was the smartest thing he'd ever done, adding, "It's also as close to Lou Reed as you're probably going to get, for better or worse."

In 1980, the first time we talked, I asked what Reed thought was the main misunderstanding about him: "I don't think people realize the sense of humor that's running through these [songs]. To say my sense of humor is dry is in itself a dry joke. I think I'm very funny. I find most things very funny.”

Reed wrote what he called "adult rock ‘n’ roll" — music that teenagers raised on rock might want to hear as they grew up. “I'm saying you can have a real good time," Reed told me in 1992. "Just on a different level. … You know, where is the rock equivalent of 'A Streetcar Named Desire'? Is that such a far-fetched idea? Is that completely impossible? That's like having your cake and eating it. As you get older, be able to have that level of writing plus the fun of rock. Why would you want to listen to what an 18-year-old is getting off on?"

Reed said that his handful of upbeat songs — say, "I Love You, Suzanne," "Crazy Feeling” and "Banging on My Drum" — tended to surprise and even shock fans, but said, "People have always been happy that I've been happy. I mean, maybe the attitude is: 'If Lou Reed can get it together, then who can't?' "

As an artist, and as a person, Reed was nothing if not mercurial. At times, he would feign indifference about the Velvet Underground’s legacy, being more focused on what was in front of him, his solo career. But he also told me, “What could be a cooler thing to be a member of? It's like playing for the New York Jets when [Joe] Namath was there."

Reed, who died at 71 four years ago, was notorious for excoriating rock writers and conducting contemptuous, combative interviews. The granddaddy of those encounters was the series of drug-fueled, hostile sessions he did with the late Lester Bangs for Creem magazine.

DeCurtis says he would not have called Reed a friend, per se, but they were on friendly terms. Like DeCurtis, I, for whatever reason, had a good relationship with Reed, over two decades of reviewing and interviewing him. There could be testy moments — especially if I wanted to ask about a song’s meaning and he wanted to go on a spiel about musical gear.

One time back in the mid-'80s, Reed was at the now defunct Kenmore Square punk club the Rat to introduce a concert film he’d done. Following that, he was to chat with some press and radio folks upstairs in the office.

Rocco LaMonica, who worked at the Rat back then, recalled the gig in a comment on Rocker Magazine: “Lou Reed was so f----- up we had to carry him on stage and physically hold him up while he introduced his own video with these immortal words, ‘Hope ya like this s---. I need a drink.’ ”

I saw that brief appearance, too. I followed Reed upstairs with half a dozen others, Rat employees and his attaches. We all sat in a semi-circle, talking nervously, quietly — aware of the elephant in the room. He sat by himself, silent, somewhere between petulant and comatose.

But that was an anomaly. Reed and I talked a fair amount over the years, about serious, difficult subjects, certainly, but not without a certain playfulness. We had scheduled one interview in the late-‘80s for a Sunday afternoon, when both of us realized it was to take place during NFL football. Reed was a Jets fan; I a Patriots fan. We both wanted to watch the game — he called me back at half-time.

Many of Reed’s songs cut to the core, whether sung in third person or first. I’m not sure if there’s a more chilling, sad and violent song than "Street Hassle" (a song Bruce Springsteen contributed an uncredited spoken word monologue to).

“I wouldn't want to come off as glib or trendy or secondhand,” Reed told me in ‘98, “but I'm out there trying to chisel something out of that rock of words available to us. Some of what I like is using words common to all of us and that is the challenge to me: to be able to use them so it can go directly to your heart. Hope that doesn't sound pretentious."

Many fans, at least on first blush, tend to think of Reed’s songs as autobiographical. "Walk on the Wild Side," Reed’s only hit single, certainly was largely that. DeCurtis says he initially heard many of Reed’s songs that way. In the book, DeCurtis spends a fair amount of time trying to unravel the complicated relationship Reed had with his parents, and the oft-negative portrayal that coursed through many of his songs. “Kill Your Sons,” for instance, is explicit and angry, about Reed being sent away for electro-shock treatment when he was a teenager and it’s not pretty.

“I took Lou’s stories about his family experience pretty much straight,” DeCurtis says, about his initial exposure to “Kill Your Sons.” “I took it as a diary. We [think we] know the story. But even that is more complicated. They were middle class suburban parents trying to contend with a very difficult child.”

Reed told me he drew inspiration from his own life, but most songs tended to be "amalgams of people." He acknowledged the blurred lines between his own life and the fiction in his music, but stressed that it was his job as a singer to sell the songs as real. "They're very personal," he said, "done with a great deal of distance. I try to keep myself invisible."

When he was younger, Reed shot methamphetamine and drank heavily. He wrote songs about copping and doing drugs (“Heroin,” “I’m Waiting for the Man,” “White Light/White Heat” and “How Do You Think It Feels?” to name four) and one called “The Power of Positive Drinking.”

By the mid-‘90s, his drugging and heavy drinking days were behind him. But I can’t say he seemed exactly happy about not drinking.

In 1996, we were in his Manhattan office, Sister Ray Enterprises. Reed was dressed, as usual, in a plain black T-shirt and faded blue jeans. He offered me Kaliber non-alcoholic beer. “Oh, great,” I said, gamely, trying to be polite and Reed shot back — and I’m paraphrasing here — "No, it is not great."

The talk turned to depression, something he battled all his life. He said he tried to look at it like the hands on the face of a clock. The minute hand may be on 6, he said, but inevitably it will come back to 12. Sounded simplistic, maybe, but I got it: Life is cyclical, not linear. I thought of his line in "Pale Blue Eyes": "Down for you is up."

This was the year his formative band, the Velvet Underground — influential to generations of punk and post-punk bands — was being inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and he was musing about rock star mannequins that were situated in the museum. I asked if he’d like to see himself there.

"Absolutely,” he said. “Before I'm gone I'd like to see myself stuffed and on display.”

Why? “So, I'm able to bitch and moan about the look."

That was quintessential Lou Reed.

Yet, so was this: When his “Magic and Loss” album came out in 1992, some people carped that Reed wrote too much about death. But Reed demurred. "I remember reading this book by Saul Bellow,” he told me, “where he was quoting Walt Whitman and he said, 'Until Americans and American poetry can deal with death, this is a country that has not grown up.' There might be something to be said about that."

In his exhaustive and detailed book, DeCurtis leaves few stones unturned. He examines Reed’s Long Island upbringing and Jewish roots, his influx sexuality, his early songwriting as part of a Pickwick Records assembly line team, his dance with Andy Warhol and the Factory scene in the late-‘60s, the successes and failures with the Velvet Underground and his complex relationship with its co-founder John Cale. Boston plays a prominent role in the Velvet Underground days, too, as they became almost a house band for the now defunct Tea Party club.

And then there are the girlfriends and wives, who seem to matter a lot (and then not at all), including his mysterious lover and muse, a transgender woman named Rachel.

“That was another element of Lou’s life that I had no idea of how serious it was,” says DeCurtis. “Rachel sort of bookended two of his best songs, ‘Coney Island Baby’ and ‘Street Hassle.’ Lou made this point, using the pronoun of ‘him,’ writing about this guy in a song. Not to mention publicly being seen as a partner of a trans-sexual person. Lou would speak of himself as being gay at various points, but I don’t think he was ever really comfortable with that.”

DeCurtis delves deeply into Reed’s self-destructive and antagonistic behavior: the drugs and booze (he died from liver disease not long after a transplant), Reed’s habit of turning against his musicians when he felt threatened by their prowess or acclaim and even his own music, calling an album his best work upon release only to deride it in subsequent years. DeCurtis sheds light on Reed’s paranoia and his penchant for sabotaging himself — whenever he got close to the rock star status he craved, he’d shoot himself in the foot.

Whatever peace Reed seemed to feel came in his relationship with avant-garde musician and performance artist Laurie Anderson, starting in the early ‘90s and culminating in a spur-of-the-moment marriage in 2008. Reed, who once shaved a swastika into his close-cropped hair in the ‘70s, embraced Judaism more fully later in his life. He found balance in practicing tai chi.

“I am so proud of the way he lived and died, of his incredible power and grace,” said Anderson in a eulogy that’s recounted in the biography.

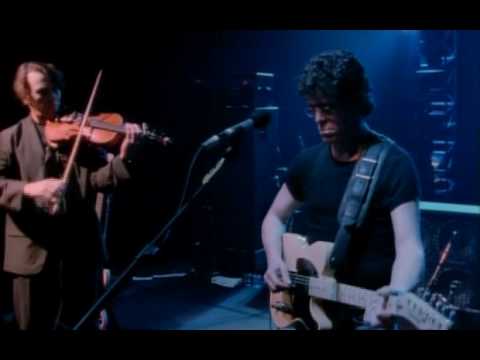

The last time I saw Reed play live, he was on electric guitar, accompanying Anderson on a music and spoken word show at Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art in 2009. It was Anderson’s show; he was the sideman and never spoke or sang. He seemed very content in that role.