Advertisement

Remembrance

Remembering Poet Richard Wilbur, Who Fused His Effortless Skill With An Honest Complexity

I was introduced to the poetry of Richard Wilbur, the celebrated poet who died Saturday at the age of 96, by my favorite undergraduate teacher at Queens College, Mary Doyle Curran. She wasn’t supposed to include contemporary American poetry in her survey course but felt that students shouldn’t graduate without some knowledge of the best poetry of our own time. So she read us Robert Lowell, Elizabeth Bishop, James Wright and Richard Wilbur.

And my first Wilbur poem, “Year’s End” (1950), is still one of my favorite of his poems:

Now winter downs the dying of the year,

And night is all a settlement of snow;

From the soft street the rooms of houses show

A gathered light, a shapen atmosphere,

Like frozen-over lakes whose ice is thin

And still allows some stirring down within.I’ve known the wind by water banks to shake

The late leaves down, which frozen where they fell

And held in ice as dancers in a spell

Fluttered all winter long into a lake;

Graved on the dark in gestures of descent,

They seemed their own most perfect monument.There was perfection in the death of ferns

Which laid their fragile cheeks against the stone

A million years. Great mammoths overthrown

Composedly have made their long sojourns,

Like palaces of patience, in the gray

And changeless lands of ice. And at PompeiiThe little dog lay curled and did not rise

But slept the deeper as the ashes rose

And found the people incomplete, and froze

The random hands, the loose unready eyes

Of men expecting yet another sun

To do the shapely thing they had not done.These sudden ends of time must give us pause.

We fray into the future, rarely wrought

Save in the tapestries of afterthought.

More time, more time. Barrages of applause

Come muffled from a buried radio.

The New-year bells are wrangling with the snow.

Here are the familiar Wilbur shapeliness, are the elegant, traditionally rhymed stanzas, with their formal rhymes and regular iambic pentameter. No technical breakthrough. And he’d continue writing in this vein for more than 70 years. And yet the poem holds up, because the chiaroscuro tone, the shadow of darker truths, feel genuine and earned. And for this apparently effortless skill and craft, he earned many awards, including two Pulitzer Prizes and a National Book Award, and was appointed Poet Laureate.

And yet, I think that Wilbur will be remembered best for some of his other writing. For one thing, his marvelous rhymed translations of Molière and Racine. Here’s the witty opening of Molière's "The Misanthrope" — the two friends, Alceste (the depressive title character) and Philante, are (of course) arguing:

Philante: Now what’s got into you?

Alceste: Kindly leave me alone.

Philante: Come, come, what is it? This lugubrious tone…

Alceste: Leave me, I said, you spoil my solitude.

Philante: Oh, listen to me, now, and don’t be rude.

Alceste: I choose to be rude, sir, and hard of hearing.

Philante: These ugly moods of yours are not endearing;

Friends though we are, I really must insist…

Alceste: Friends? Friends, you say? Well cross me off your list!

These lines, for all their formality (Wilbur changes Molière’s six-beat hexameters for the more familiar rhymes of English heroic couplets), convey the easy exchange of convincing conversation. The rhymes add to the liveliness of the repartee. And Wilbur catches the misanthropic character of Alceste from his very first line.

But I have to admit that my favorite work from Wilbur are the lyrics he wrote for Leonard Bernstein’s 1957 operetta, “Candide.” He was the major lyricist but not the only one. There are lyrics by Lillian Hellman, who wrote the now unperformed book to the show, Dorothy Parker, John La Touche, and even Bernstein himself. But the greatest ones, the most biting, are by Wilbur, including Dr. Pangloss’ aria about contracting syphilis, and what’s probably the best known music in the entire score, the heroine Cunégonde's mock-heroic “Glitter and Be Gay,” in which she sings with all-too-knowing irony about how in the light of having lost her virtue, she must force herself to enjoy the glamorous and expensive jewels she has accumulated:

Pearls and ruby rings...

Ah, how can worldly things

Take the place of honor lost?

Can they compensate

For my fallen state,

Purchased as they were at such an awful cost?Bracelets...lavalieres...

Can they dry my tears?

Can they blind my eyes to shame?

Can the brightest brooch

Shield me from reproach?

Can the purest diamond purify my name?And yet, of course, these trinkets are endearing!

I'm oh, so glad my sapphire is a star!

I rather like a twenty-carat earring!

If I'm not pure, at least my jewels are!

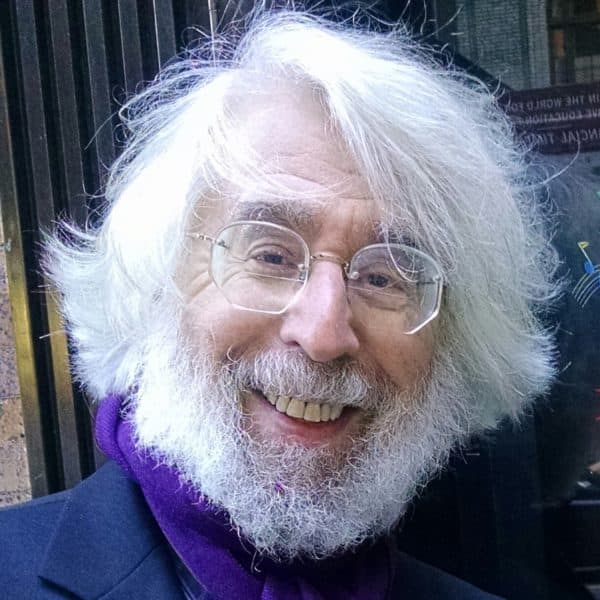

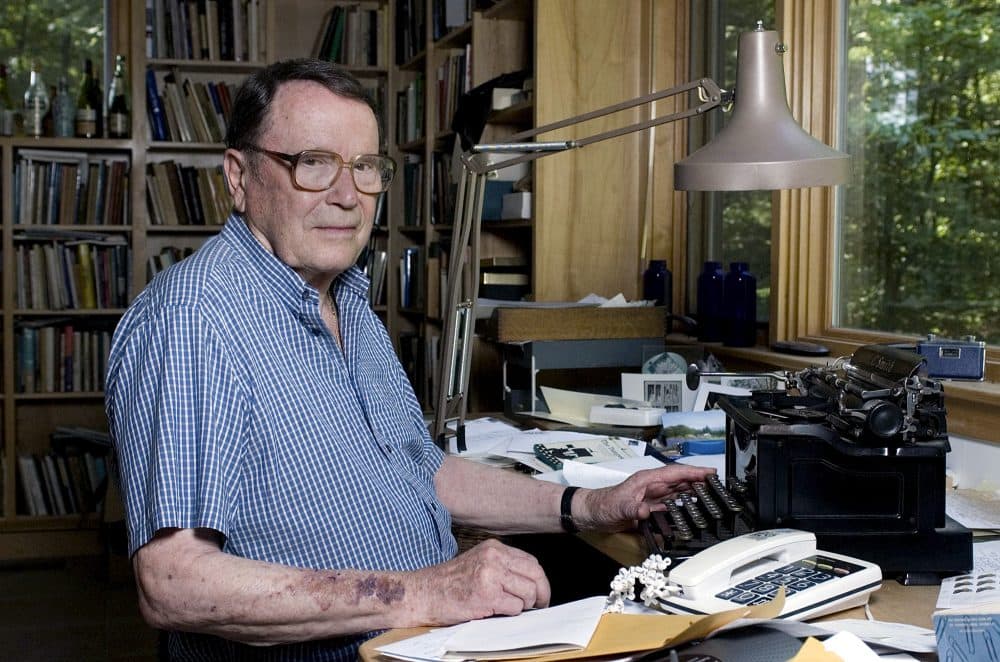

Wilbur was famously handsome and fit. Here he is in the late 1970s, in Duxbury, playing croquet with Elizabeth Bishop.

Those qualities seem to have rubbed off on his poems. I’m not sure he broke any new ground, although in a century in which American versification became increasingly “free,” he inspired a group of “New Formalists” to return to older traditions. He was also attacked for that. But I’m convinced that his best poems — his best writing — will last, because underneath the consistently smooth and often dazzling surface is something honest, real and complex.