Advertisement

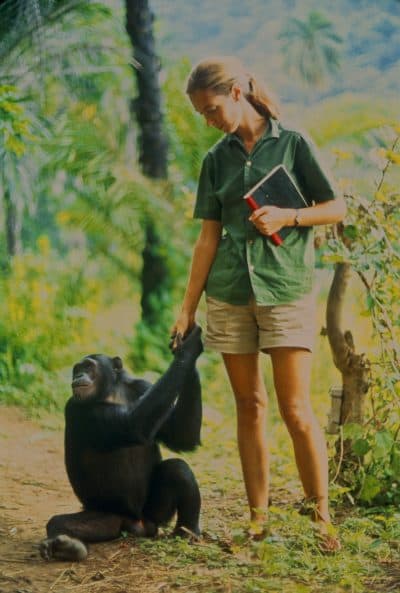

'Jane' Goodall Documentary Is A Love Story About A Woman And Her Work

Brett Morgen’s “Jane” is one of the year’s most thrilling movie experiences. Assembled from over 100 hours of 16mm footage recently rediscovered in the National Geographic archives, the film brings us along with young Dr. Jane Goodall to the outer reaches of Tanzania’s Gombe Stream National Park, where her pioneering research on chimpanzees revolutionized our scientific understanding of the natural world. But as the director insisted over the phone earlier this week, “This is not a film about science. I failed science. It was my worst subject. This is a love story about a woman and her work. From the first conception, it was intended to be a sort of cinematic opera.”

With dazzling documentaries like “The Kid Stays in the Picture,” “Chicago 10” and “June 17th, 1994,” Morgen has made a career out of wrestling mountains of archival footage into viscerally cinematic entertainments that buck the conventions of the form. But a guy known for chronicling rebels and rock ‘n’ rollers hardly seems a likely fit for National Geographic. When the venerable institution came calling, Morgen was in a dark personal place, reeling from the controversies that greeted his grueling 2015 masterpiece, “Cobain: Montage of Heck.”

“People think that the experience of making ‘Montage’ was what f----- me up,” he tried to clarify. “Making ‘Montage’ was really a creative high. We were working with some extraordinary footage about one of the most creative minds of our time.” But his brilliantly compassionate, collage-like profile of late Nirvana frontman Kurt Cobain soon found itself swarmed by the kind of ridiculous rumors and scandals that continue to haunt the subject’s widow Courtney Love and that entire incestuous Seattle music scene some 20-odd years after Cobain’s suicide shook the world. Morgen still sounded troubled by the movie's reception.

“It was f------ crazy, dude. You know what it was? I was living inside a conspiracy, and it was the strangest thing to be on the inside and to see and read these things people were saying. I literally was in the twilight zone. Bringing ‘Montage’ on the road was a disturbing and emotionally painful experience. I definitely, coming out of that, needed to try and do something a little more aspirational, with a little more light.”

The director was so dispirited he’d publicly contemplated throwing in the towel, but then “ ‘Jane’ found me,” he explained. “They all find you, man. And at the time I had no idea how cathartic it would be to work and present this film to the world.” He also had no idea at the time quite how much work it would entail. When the footage finally arrived, Morgen and his team were in for a big surprise.

“National Geographic assured me that they were sending 140 hours of pristine 16mm that had already been organized. It became clear within moments that what we were dealing with was 140 hours of individual shots. There was no continuity between two shots anywhere on these reels. They featured 160 different chimpanzees, none of whom were wearing name tags. There was no sound. Just the act of being able to screen through the footage was a bit of a Herculean task. We had to shut production down for six months while we thematically joined shots together just so we could screen through it.”

But in that process came a great discovery. Goodall and photographer Hugo van Lawick famously fell in love while working together in Gombe, a spark that becomes quite obvious to us viewers in the glimpses of footage Morgen found between professional setups. “I’m seeing a shot of Jane sort of being composed looking out somewhere,” he recalled. “And then at the end of the shot, before it flares out, I see her look over to the camera and start smiling. I instantly recognize what’s happening, in that she’s breaking down that fourth wall and we’re going to be able to tell this love story in this rather unique manner.”

He and his team combed the footage for these kind of revealing moments. “Hugo was such a perfectionist, there were very few shots when the camera was not mounted on a tripod. We knew instantly that every time the camera was handheld or facing the ground it was going to be gold. So anytime there were any flares or any mistakes we were all over it.”

It’s tough to come up with a bigger study in contrasts than going from Kurt Cobain to Jane Goodall. “Jane is probably more comfortable in her skin than any human being I have ever met,” Morgen enthused. “She’s utterly unflappable. I don’t think Kurt, from what I was able to gather, ever had that kind of peace in his life.” I imagine that just watching “Jane” and “Cobain: Montage of Heck” back-to-back would be enough to induce whiplash, to say nothing of directing them both.

“We’re doing a double bill in London next Sunday,” he laughed. “I’m like, which one do you show first?”

“Jane” opens Friday, Nov. 3 at the Kendall Square Cinema in Cambridge.