Advertisement

From Boston To Miami And San Francisco, Conductor Michael Tilson Thomas' Legacy Is Far-Reaching

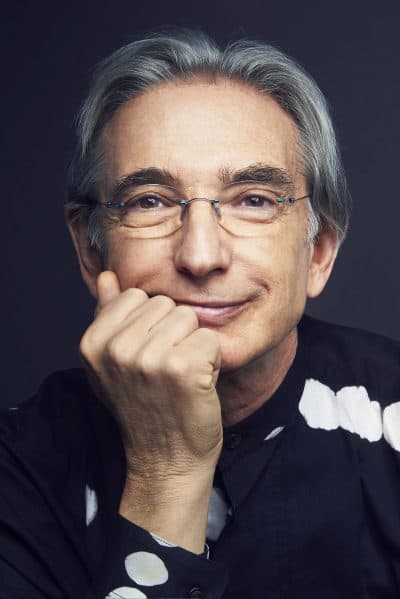

You don’t think of his legacy when you look at Michael Tilson Thomas.

The eternally boyish conductor, at 73, seems decades younger. Fit, handsome, energetic and engaging, you wonder instead what his next unusual project will be like — not his retirement.

But he is retiring — in 2020, from his 25-year directorship of the San Francisco Symphony — leaving an orchestra that he has turned into one of America’s most popular. But as almost anyone who approaches a certain age will quickly tell you, MTT’s retirement has little to do with long-distance RV trips or shuffleboard cruises.

MTT’s Boston connections run deep — including his splashy debut, filling in for William Steinberg mid-concert in 1969, and staying on until 1974 as as associate conductor for Boston Symphony Orchestra; his formative Tanglewood experiences before that, especially his relationship with Leonard Bernstein; and his occasional guest appearances. These seem distant, but remain vivid when he discusses them.

For Boston, he is the one who got away. It’s easy to paint the long Seiji Ozawa years at the BSO with one brush — at the end of his tenure (1973-2002), the conductor and the organization were clearly tired of each other. But the beginning was much different: beaded, long-haired and exotic, Ozawa seemed like a perfect match for the BSO. For a long time he was.

But MTT could have made that match as well. By the time Ozawa was named music director in 1973 (ironically, after a stint in San Francisco), MTT had already conducted the BSO dozens of times, and recorded prolifically. One glimpse at the repertory list of Deutsche Grammophon’s mammoth BSO box set shows Tilson Thomas conducting William Schuman, Carl Ruggles, Tchaikovsky, Debussy, Stravinsky, Ives — a sense of involvement that stands in contrast to the very few engagements he’s had with the orchestra since those years.

He was a Tanglewood wunderkind — but so was Ozawa. He had already stepped in for the orchestra in need — Steinberg’s years at the BSO were much like the subsequent James Levine years, full of absences. He was in Boston as assistant conductor when Ozawa was off to San Francisco (and other orchestras).

But Ozawa got the job, and stayed — for a long time. MTT led many orchestras after that — Buffalo, Los Angeles, San Francisco, the London Symphony Orchestra and most influentially, his own New World Symphony, which he founded 30 years ago. If he had stayed in Boston, the BSO’s past few decades might look much different. The innovative programming and community connections that NWS has established in Miami — certainly reflected in its younger, more diverse audience — could have transformed concert-going in Boston into a less stodgy affair.

Tilson Thomas comes back to Tanglewood this summer, making multiple appearances, most notably on the star-studded final weekend celebration of Bernstein’s centenary. He joins Andris Nelsons, Keith Lockhart and John Williams on the podium, conducting Yo-Yo Ma, Audra McDonald, Midori, Susan Graham, Thomas Hampson and others in a gala concert of Bernstein’s music.

It is more than symbolic that when the BSO wants to remember Bernstein’s connections to Tanglewood, it is Tilson Thomas who comes back to the podium. MTT also conducts a major program in the Shed (Aug. 12), which includes a work of his own, “Agnegram,” and pianist Igor Levit performing Rachmaninov’s “Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini.”

He will definitely not be leaving Miami’s New World Symphony — not anytime soon. The ensemble, which he founded to provide post-doc training for top-flight conservatory graduates, will continue to benefit from his leadership, and his programming initiatives. The New World Symphony is the cornerstone for the arts in Miami Beach; MTT took his talents here, and he’s staying.

NWS’s glittering, Frank Gehry-designed New World Center stands as a versatile monument to MTT’s energy, his artistry and his ability to bring others — read, donors — along with him. Completed in 2011, the New World Center mirrors the orchestra: flexible, somewhat brash, able to accommodate any of the art forms and facilitate an interesting conversation. The hall itself dismisses the notion of fussy manners that haunts classical music performances — no clapping, how to dress, all that. In fact, NWC sometimes turns itself into a late-night club with its PULSE series.

There is no doubt that the New World Center is built for the future. The performance hall comes with five overhead video screen “clouds” available for simple things like supertitles, and for complex things like multiple film montages. A huge outside façade serves the WALLCAST series — live outdoor screenings of the music being performed inside.

Apart from the indoors and outdoors video capabilities, the stage itself swivels, separates and lifts, providing functional adjustments to seat the orchestra and the parade of actors, dancers and spoken-word artists that collaborate with NWS.

Musicians audition for NWS, and the lucky few — 35 new fellowships each year, selected from more than 1,500 applicants — are housed by the organization, and trained at the highest levels for three seasons. Then they are off to the real world with a new top line on their resumés. Training is varied and challenging.

The symphony plays a concert season, with plenty of the standard repertory. But the emphasis is on collaboration. A Saturday evening concert featured one premiere with a conductor/composer (MTT) reading from a memoir; another world premiere — but a play about PTSD; and a third piece, a crowd-sourced film with orchestral score. No other professional symphony would dare mount such an evening.

It was a chaos of art forms, fully representing MTT’s notions about teaching musicians. “The first six months at New World Symphony can be different than anything they have ever done,” he says. “I encourage them to color outside the lines, and I work with them as a director would work with actors. I don’t tell them what to do; I want them to recognize things intuitively, about themselves, in pieces.”

The performance itself had direct hits and clear misses. MTT’s three short pieces from “Glimpse of the Big Picture” may someday be a major work that encapsulates his career, “but I’m not even thinking like that now,” he says. The stage was then turned topsy-turvy — an overlong delay for a non-intermission interlude — for Christopher Wall’s affecting “The Inherent Sadness of Low-Lying Areas,” a touching short play with a harrowing undercurrent.

“Miami in Movements,” a slight revision of an October premiere, used technology developed at MIT’s Media Lab to crowdsource a symphonic pastiche about Miami’s vast neighborhoods. Ted Hearne’s score was inventive, alert to the possibilities in the film montage. Most of the crowd-sourcing showed up as spoken-word reminiscences by Miamians. Filmmaker Jonathan David Kane treated his city — he is a native — like a living organism, emphasizing its neighborhood’s intersections, not its divisions.

All three works were specific to Miami, and to the NWS. It would be hard to imagine them performed anywhere else — a shortcoming for the future of these pieces, but not of the performance. It was both well-attended and received, brilliantly played and acted.

MTT knows that NWS has grown from his original vision — a vision that was formulated at Tanglewood long ago, when he was a young conducting star. “I wanted this to be a continuation of the idea of Tanglewood,” he says. “I remember the end of one summer there. So many of the students there had only a sketchy idea of what to do afterward. One percussionist — a fantastic player — told me he was getting a job at Dominos just so he could keep practicing. That was really the genesis of what this is.”

“When it started 30 years ago, I knew absolutely everything that was going on here,” he says of NWS. That certainly has changed. But even with the San Francisco retirement, and his claim that he wants to compose more — “I’ve spent so much time making other people’s music work” — there is no notion that a succession plan at NWS is in the offing.

When asked what kind of person might replace him — conductor, composer, educator — he changes the subject to his next performance, Stravinsky’s “Firebird.” “That’s all I’m focused on now,” he insists, launching into an enthusiastic treatise on differing ways to approach the classics. Typical: no talk of legacy, just on to the next project.