Advertisement

Review

Beyond Glamor And Gold, Beyond Sex And Scandal — The Beautiful Renderings Of Klimt And Schiele At The MFA

The early 20th-century Viennese artists Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele — who are being celebrated in an exhibit of their drawings, “Klimt and Schiele: Drawn,” at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts through May 28 — might seem almost polar opposites.

Klimt is most famous for his glamorous, luxurious, richly textured paintings, often glistening with gold (his father was a gold engraver). Schiele is best known for his sexually charged, garishly colored images, with figures often distorted, even grotesque. Klimt was 28 years older than Schiele, but they were friends and admirers of each other’s work. They both died in 1918, Klimt at the age of 56, from the after-effects of a stroke complicated by pneumonia; Schiele at 28, in the notorious Spanish influenza epidemic, three days after the death of his pregnant wife.

“Klimt and Schiele: Drawn” is the Boston version of a three-pronged Klimt/Schiele show of works on paper from Vienna’s legendary Albertina Museum honoring the centenary of their deaths. The first show, at the Pushkin State Museum in Moscow, just closed and the one at London’s Royal Academy opens in November. Each venue was offered a different selection of drawings. I found the show at the MFA, the only one in America, as beautiful as it is revealing.

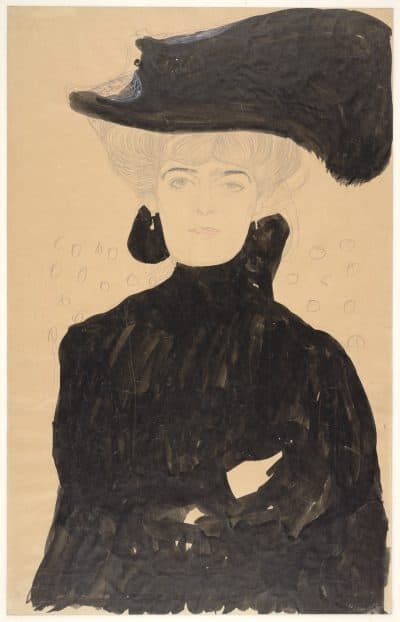

Curator Katie Hanson has judiciously chosen 60 works (the other venues had closer to 100). Klimt’s drawings are more often than not austere pencil studies for more ambitious paintings, murals and the notorious “Beethoven Frieze” he did in 1902 for the Vienna Secession building. One of his portraits delicately uses several different color pencils and one, “Lady with a Plumed Hat,” uses ink, colored pencil and black watercolor and looks almost like a Toulouse-Lautrec poster.

Schiele’s drawings are mostly dazzling watercolors, self-contained works made to sell individually. Hanson essentially divides the MFA’s Torf Gallery in half, with Klimts and Schieles for the most part on opposite sides, with a couple of free-standing walls of each in between. And she organizes the show both chronologically and by various categories, most of which the two artists have in common: Inner Life Made Visible, The Stuff of Scandal (both artists had their share), Nudes, and Portraits.

I found Klimt’s carefully rendered and more “realistic” nudes rather more salacious than Schiele’s more overtly expressionistic ones, although Schiele’s notorious images of inextricably entwined lovers — here one heterosexual and one lesbian couple — would be more likely to shock the early 20th-century censors. Among the Klimts that really knocked me out were three early studies for his mural “Shakespeare’s Theatre.” He evidently used a separate model for each member of the audience watching “Romeo and Juliet” at the Globe Theatre. Drawn with black and white chalks on wrapping paper, the heads of Juliet on her deathbed (the model’s address is written in the upper left hand corner), a young boy, and an older man in the audience in rapt attention are so three-dimensional they practically leap off the page.

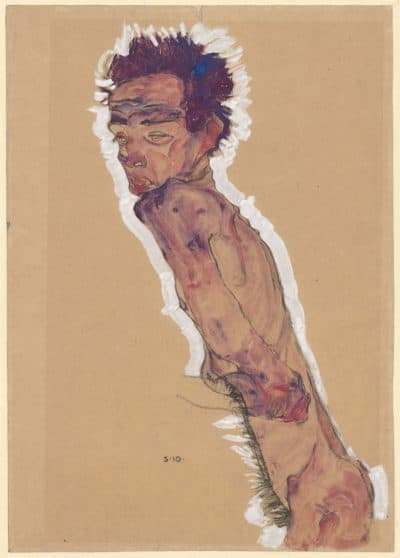

All of Klimt’s nudes are women. Some of Schiele’s best known nudes are self-portraits. One of them shows a very thin jagged-edged body in profile, his hair on end, as the caption says, as if electrified. “Bodies have their own light,” he wrote, “which they consume during their lifetime; they burn; they are unlit.”

Several Schiele bodies are particularly unsettling because of the direction in which he wanted them to be hung. One is a self-portrait from when he was in prison (he was accused, but cleared, of assaulting a young girl, but imprisoned for allowing her to be in a room with his drawings of nudes), and the other is an image of his mother sleeping. In both drawings, the figures seem to be floating — their hair shooting up against the pull of gravity. In fact, they are both lying down. The pictures would make more immediate sense if they were horizontal rather than vertical. But we know from the way Schiele signed them that he wanted them to be seen vertically — that he wanted the viewer to be disoriented.

The biggest surprise about Klimt will probably be the almost wispy quality of the pencil line, the spareness and simplicity of so many of these drawings (as opposed to his over-ripe paintings). With Schiele, the surprises are mainly in subject matter. His searing portraits — of himself, his wife, his sister-in-law, and fellow artists — are hallmarks of his work, but I was unfamiliar with his touching images of children. And even more astonished by his watercolors with no people in them at all.

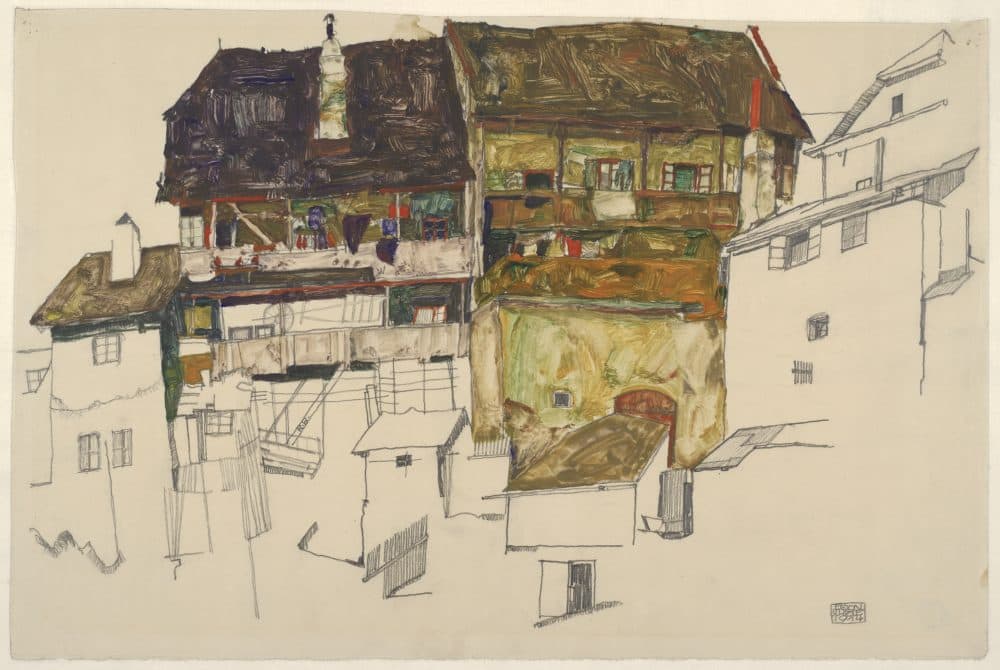

Five of these, labeled “Plants and Places,” are all on one of the free-standing walls. They include the coruscating “Yellow Chrysanthemum” (what an uncanny yellow for this fragile dying flower) and “Red Chrysanthemum.” “Only one in a thousand perceives the organism of all things and recognizes in the inner life and countenance of plants a vivid hint of their faces.” (I wonder if Robert Mapplethorpe knew these floral images.) Two boats huddled together in “Trieste Fishing Boats” float vividly on a blank background. In “Old Houses in Ceský Krumlov” (the birthplace of Schiele’s mother), the buildings at the top of the hill are densely painted but the houses beneath them are only sketched in, just as the mountain in “Group of Houses on a Mountain” is more a cloud than a mountain, compared to the thickly colored houses.

“The transience of human life is paralleled in the visible signs of transitoriness of inanimate objects,” Schiele wrote (he was an eloquent writer). “In the autumn nature seems to be filled with a vegetal melody that also exudes from old walls and fills the heart with sadness reminding us that we are all but pilgrims in this world.”

The MFA seems to be taking wall copy more seriously than ever, or than most other museums. In the recent Munch show at the Met Breuer, a label informed us that a painting of a woman alone in a room was a painting of a woman alone in a room and that the image suggested loneliness. Did someone think that people coming to see an immensely popular artist had to be treated like children? The MFA currently has exhibits of two other equally “popular” artists, Escher and, here, Klimt. Ronni Baer, the curator of the Escher show, actually commissioned commentary from figures in science, history, the arts and architecture, education, an astronaut, writers (full disclosure, I was one of the invitees), and such local and national luminaries as Yo-Yo Ma, James Carroll, Barbara Lynch and Diane Paulus. The commentary for “Klimt and Schiele: Drawn” is both economical and eloquent (especially Schiele’s own statements), leading us both into the images and giving us something to take away from them. They are also posted at waist level, beneath the images rather than adjacent to them, so they are both readable and not distracting.

It’s good to see the MFA taking such popular artists as Klimt and Escher seriously in such elegant and thoughtful installations. The Klimt drawings reveal a hitherto unknown (or at least lesser known) side of the artist. And if Schiele is new to the visitors who come because they want to see Klimt, they are in for a tremendous treat. As are we all.

“Klimt and Schiele: Drawn” is at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts through May 28.