Advertisement

Watertown Library Wants To Unite A Community Through A Book

"Without stories the village has no life," Dr. Bahman Hamidi’s father once told him.

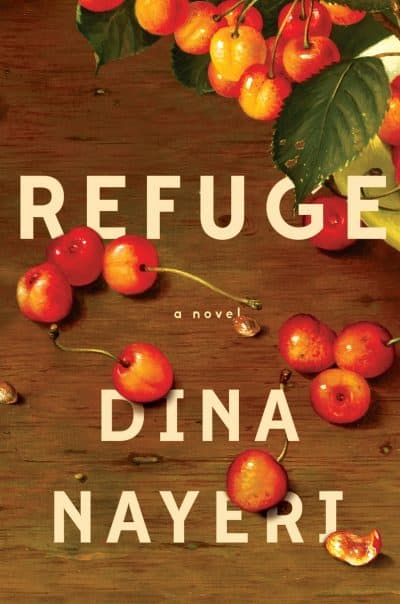

When we find the fictional dentist — in court in Iran in 2009, seeking a divorce from his third wife — Bahman is a storyteller who has lost his village. His first wife fled Iran with their daughter and son for the United States 22 years before. Over the course of the four visits with his two children tracked in Dina Nayeri’s 2017 novel, “Refuge,” Bahman struggles to reconnect with them as they move across continents and through the stages of childhood and young adulthood. Through the eyes of Bahman and his daughter, Niloo, the novel traces how two decades of separation shape their lives and identities. As father and daughter drift apart, stories are the rescue lines Bahman throws out to try to hold them together.

“Refuge” is the story that the Watertown Free Public Library has chosen to bring its village together for its 10th annual "One Book, One Watertown" program. In January, the library put 100 copies of the book in circulation and released a list of related programming for the month of March. Events include an author Q&A, community discussions, music and dance performances and presentations on democracy in Iran, the psychology of immigration and adaption and the impact of opioid addiction on families. To open up the shared reading experience more widely, the library included an alternate selection this year; Firoozeh Dumas’ "It Ain’t So Awful, Falafel" explores many of the same themes as “Refuge,” but at a level more accessible to new English speakers and younger adult readers.

The concept behind the series is that bringing people together around one tale can open a conversation that might otherwise not happen. Citing a desire to help people break out of the “echo chambers” of the internet where a lot of today’s communication takes place, Jill Clements, supervisor of adult and reference services at the library says, “We want to get various voices from the community speaking and sharing and talking…” without proscribing a specific goal or outcome for those exchanges. “It’s not [about] our agenda... We want to hear Watertown voices.”

The library does shape the conversation somewhat, by choosing a theme for the year and selecting the book. Immigration is a timely and relevant topic nationally, and also locally — by one count, 35 different home languages are spoken within the Watertown school district. As it confronts the complexities of political ideology, romance, estrangement, addiction and more, “Refuge” offers rich territory for discussion of what immigration can mean for an individual and a family, beyond a simplified narrative of departure, arrival and assimilation.

Nayeri says her aim is for readers to see the full “life cycle of the refugee.” For that she has plenty to draw on from her own life. She was born in Iran and left with her mother and brother when she was 8 years old. After 16 months in Europe, the trio landed in Oklahoma. Nayeri went on to university on the East Coast (including Master’s degrees from Harvard schools of business and education), and later returned to Europe. Over the course of that time away from Iran, she saw her father only four times.

While a memoir might have been very compelling, Nayeri is deft with the flexibility and painterly strokes of what she calls “auto-fiction.” The characters’ memories over decades fold on each other, and the narrative crisscrosses the globe from Oklahoma to Isfahan to Amsterdam. Readers, however, are spared the dislocation and identity confusion that some of the characters feel. We stay rooted in the protagonists’ endearing idiosyncrasies — the dentist with a sweet tooth, the young woman who carries everything in her backpack — and in the rich detail with which Nayeri renders their worlds. She gives readers tastes of eggplant and lamb, whiffs of spice jars and fried onion. She vividly conjures the agonies of opium addiction and detox -- "the shivering growing in intensity, the skin of the arms and legs itching, the vomiting hitting violent new peaks," and the despair of asylum seekers left behind by the legal system "their lives dripping away day after day in limbo."

Stories offer a freedom that strict documentation does not, and Nayeri weaves a tale that is truthful in its complexity. As the novel's narrator puts it, “[The storyteller] doesn’t lecture or accuse. He doesn’t trouble himself with morality or justice, and he doesn’t weigh down the story with notions of the way things ought to go. He is devoted only to the creation of the most enticing tale, and so is granted leeway to hide every one of these unpalatable things in the nooks and folds of the narrative.”

Nayeri is clearly at home in the role of the storyteller, and her protagonists thrive on stories, too. Niloo finds sanctuary in an Amsterdam cafe where other Iranian expats gather to share words and pots of stew; her father, Bahman, spins tales to their steer strained, globetrotting reunions back to common turf.

The facts can be claimed by anyone, but the story is the teller’s entitlement and, especially when rendered beautifully as it is in “Refuge,” her gift to those who will listen. In an essay for The Guardian, Nayeri says she wishes her Middle Eastern students would “tune their voices and polish their stories, because the world is duller without them -- even more so if they arrived as refugees.”

Watertown is a community rich with stories, and the One Book program could help bring them out. The library solicited written narratives of “My Family Story” of immigration from patrons, including members of Project Literacy, which provides free English language instruction for adults. (Full disclosure: I volunteer for Project Literacy.) The responses are on display in the library’s gallery through the month of March, along with cartoons drawn by students from Hosmer Elementary School. Later in the month, Project Literacy students will lead a panel discussion and open a conversation about the experiences of living as a newcomer in Watertown.

While even the strongest ties -- to one’s family, or one’s place of birth -- might stretch and fray, stories endure. There’s a family anecdote about a young girl and a beloved chicken that the Hamidi family retells almost every time they are together. Even when the world fails them or they fail each other, the story never does. Watertown’s commitment to One Book officially ends at the end of March, but the program could begin to shape the community's shared narrative that will carry long into the future.

Here's a list of the "One Book, One Watertown" events.