Advertisement

Review

MFA's 'Seeking Stillness' Puts Rosso Fiorentino's Mannerist Masterpiece In The Spotlight

The haunting installation “Seeking Stillness,” in the Linde Family Wing for Contemporary Art at the Museum of Fine Arts, takes up three quiet galleries many visitors are likely to just pass through on their way to the room of Rothkos on loan from the National Gallery of Art.

The show (on through Sept. 3) includes paintings by Agnes Martin and Joan Mitchell, a wire mesh sculpture (“Confessional”) by Martin Puryear, work by Korean, Indian, and Japanese artists, Chinese rocks, Edward Weston photographs and an extraordinary Mayan “paint container” more than a thousand years old carved from a conch shell into the shape of a hand, possibly the hand of the artist holding it. Two early John Cage piano pieces — “In a Landscape” and “Dream” — float dreamily through the galleries. One of the first items you encounter is a painting like nothing else in the exhibit — Rosso Fiorentino’s “Dead Christ with Angels” (circa 1526), one of the less familiar masterpieces in the MFA’s collection and its supreme example of 16th-century Italian Mannerism.

This large oil painting, on a panel almost 4.5 feet high by 3.5 feet wide, has never been well displayed by the MFA, at least not in my lifetime. For years, it’s been crammed into a little side room full of incongruous Medieval art, near the top of the circular staircase. Before that, it was on a huge wall in the grand tapestry room surrounded by too many other paintings vying for attention. It’s never been either adequately lit or adequately described.

Rosso Fiorentino ("Redhead from Florence") was the nickname of Giovanni Battista del Jacopo — a student of Andrea del Sarto and a contemporary of another great Mannerist painter, Jacopo Pontormo. He had a complicated but all too brief career, and died at 45, a possible suicide according to the 16th-century artist and biographer of artists Giorgio Vasari. And, as one can see from Christ’s contorted, muscular body, Rosso was clearly influenced by the figures in Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling frescoes, which he saw when he moved to Rome. He ended up spending his last 10 years as a painter in the court of France, where his major work was at the Château de Fontainebleau.

“Dead Christ with Angels” was evidently intended as an altarpiece for a private chapel, but was never installed. When Rosso fled the city during the Sack of Rome in 1527, he seems to have left this painting with an Italian nun, from whom he later tried (but evidently failed) to retrieve it. In the early 19th century, it was acquired by King Charles IV of Spain. It was later confiscated from a descendant of his by Queen Isabella II, then ultimately returned to its former royal owners. In 1958, it was sold to the MFA.

Since we don’t know in which room the Rosso will wind up after Sept. 3, I encourage you not to miss it in its current situation. In the first room of the “Seeking Stillness” show, there’s a little area set aside on the right — austere, a kind of cross between a chapel and a tent, with a single bench for leisurely contemplation. Inside is “Dead Christ with Angels.” The wall is the same deep carmine as the robe of one of the angels. The painted surface is intense and radiant and there’s (at last) enough light to allow a clear view of the details. (You can enlarge the details by clicking on them on the MFA’s website.)

Posted on a side wall is a lucid explanation of what’s in the painting (written by the MFA’s Adam Tessier). Two of the angels, for example, are holding large, extinguished candles. The flame has gone out, we are informed, because the boulder covering the entrance to the tomb has been pushed aside and a gust of wind has just blown out the candles. If we look closely, we can see the crown of thorns entwined in Jesus’s curly reddish hair and the nails and sponge of the crucifixion lying on the ground, though it may be harder to determine that we’re actually looking into a tomb. The good lighting reveals other qualities perhaps impossible to see before. Rosso incised the outlines of each figure into the wooden panel. And you can see “pentimenti,” the traces of little changes Rosso made to his original conception — the way he decided to readjust the central pose, moving a leg or an arm a little to the right or to the left. You can also make out the flaws in the wood panel itself.

The wall label suggests that this is a painting of “the very moment of Christ’s resurrection.” Are the eyes of the dead Christ just about to open?

Several aspects of the dead Christ are classic Mannerist devices. As in another notable Mannerist painter, Parmigianino (Girolamo Francesco Maria Mazzola, who painted the great “Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror” and the “Madonna with the Long Neck”), the central figure is unnaturally both elongated and twisted. And as in some paintings by his younger contemporary, Agnolo Bronzino, the figures are crowded — compacted — into the painting to the point at which it’s tricky to tell whose hands or feet belong to whom. If both hands of the angel on the left are holding his long candle, then whose is the virtually disembodied hand so tenderly (tentatively?) touching Christ’s wound? One of the gold-ringleted angels is sumptuously dressed in blue and gold brocade. Another wears a tunic of crimson satin over a blouse of green sleeves. The two angels behind them are practically absorbed into the ambiguous background, one of them barely visible in the darkness of the tomb. Each of them shows some compassionate concern.

Of course, the not quite yet risen Christ is the center of the painting, almost bursting out of a space that can’t contain him. And he’s startlingly completely nude. Muscles rippling, he has one of the most voluptuously sensual naked bodies in Italian painting. He’s lying back in a languid pose that suggests considerably less spiritual female reclining nudes. His feet, so oddly expressive, are crossed rather demurely at the ankles. He has a short beard and mustache, unusually contemporary, and his mysterious expression is entirely benign — not tormented, not angry — a look almost of gratification, almost ecstatic, but on its way to passing beyond human emotions.

The artist signed the painting in Latin: RUBEUS FLO FACIEBAT.

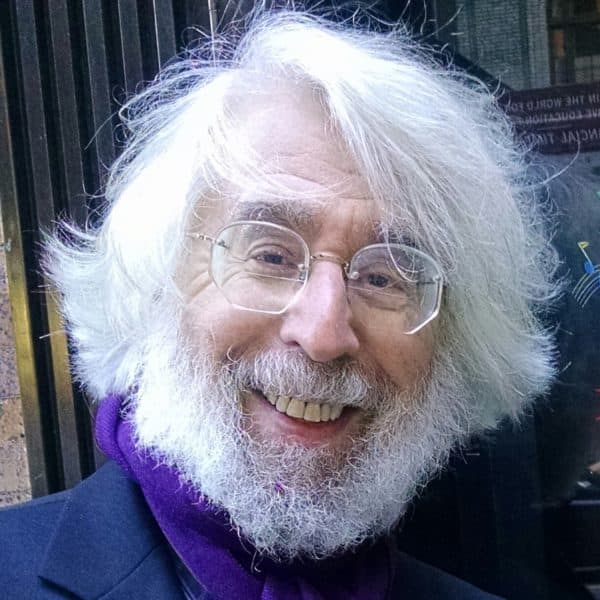

“Seeking Stillness” takes the Rosso out of its previous hiding place and literally puts it in the spotlight. This quietly beautiful show is one of the last MFA exhibits organized by curator Al Miner, who has moved on to Georgetown University, where he is now director of galleries and professor of art and art history. He and his team have left Boston art lovers with a wonderful gift, temporary but unforgettable.

The MFA’s installation “Seeking Stillness” runs through Sept. 3.