Advertisement

Essay

'Black Radical Women' Exhibition At The ICA Seeks To Correct The Record

Resume

In her 1971 mural "For The Women's House," artist Faith Ringgold painted women of different ethnicities partaking in tasks that were at once mundane and yet also required radical ambition: driving a bus at a time when women were banned from doing so in New York City, playing basketball for a professional team decades before the inception of the WNBA, being a doctor, mothering a child of a different race freely and without judgment. The 8-foot by 8-foot mural imbues solidarity — women of varying skin colors co-existing and thriving.

Ringgold's mural is the powerful opening to "We Wanted A Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965 to 1985," now on view at Boston's Institute of Contemporary Art until Sept. 30.

"For The Women's House" was created in 1971, when Ringgold had already established herself as a prominent voice of black artistry and activism, and yet she struggled to find a home for the piece. After her own alma mater, City College, turned it down, Ringgold asked herself — as she later told her daughter, the critic Michele Wallace — "Do you want your work to be somewhere where nobody wants it, or do you want it to be somewhere it is needed?”

Ringgold took the idea to the Women's House of Detention on Rikers Island, where she interviewed the incarcerated women and asked what they wanted to see. The result is a painterly manifestation of intersectionality, a call that has caught on in the age of internet "wokeness" and performative activism, but that women of color — and specifically black women — have been exhorting for generations. The truth seems obvious to us now: that the liberation from the patriarchy and the liberation from systemic racism are bound in each other. You can't fight against one, while being tethered to the other.

And yet, the second-wave feminism of the '60s, '70s and '80s operated under an imaginary and hazardous concept of racial color-blindness. All women are the same in the fight for gender equality, went the conventional wisdom of the day.

Except, they're not.

To pretend one doesn't see race, is to invalidate the hatred and systemic discrimination black women must navigate for simply existing.

While the mainstream feminist movement of the time focused on social issues, such as workplace and reproductive rights (as opposed to the legal obstacles -- like suffrage and property rights that first wave feminism tackled), black women organized, too. But their movements, including the Womanist fight, intersected with the fight against systemic racism.

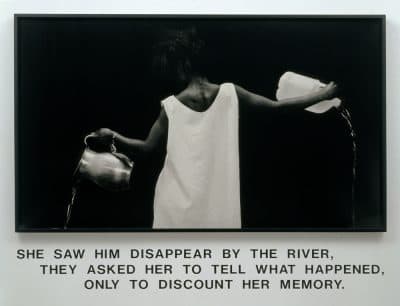

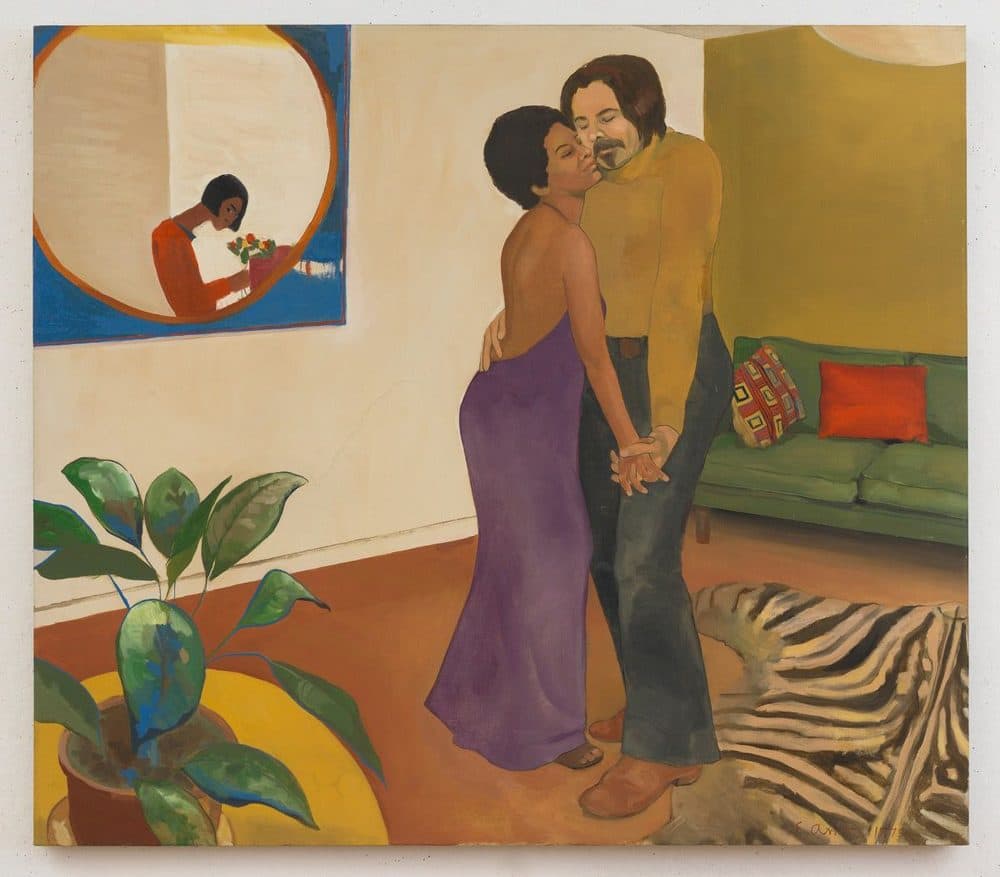

At the ICA right now, art offers a corrective — not just for the art canon, but for history. These are the voices once stifled and ignored. Emma Amos' painting "Sandy and her Husband," of an interracial couple happy, in love and safe in their own home, reminds us just how daring and subversive it is to be carefree while black in this country. Lorraine O'Grady's performance piece "Mlle Bourgeoise Noire Goes to the New Museum," in which she dressed in a gown of white gloves and crashed museum parties, illustrates how these women were on the forefront of form and the avant-garde. They were there. They were loud. But no one listened.

Who are we ignoring now?

This segment aired on August 3, 2018.