Advertisement

Crude, Hilarious And Deep: How The A.R.T. Turned 'Moby-Dick' Into A Musical For Today

Resume

The epic tale of a vengeful sea captain’s quest to kill the mythic sperm whale that chomped off his leg is filling the American Repertory Theater with song in a world premiere.

The musical version of "Moby-Dick" starts off like the Herman Melville's novel, with one of American literature’s most famous opening lines: “Call me Ishmael.”

“That sentence had to be exactly as is,” writer and composer Dave Malloy said. He felt the same about the words that follow, sung by actor Manik Choksi:

Some years ago — never mind how long precisely — having little or no money in my purse, and nothing particular to interest me onshore, I thought I would sail about a little and see the watery part of the world.

Adapting classic literature is nothing new for Malloy. He also created the Tony Award-winning musical “Natasha, Pierre and the Great Comet of 1812,” from Leo Tolstoy's "War and Peace."

“It's always fun to collaborate with these 200- or 300-year-old authors,” Malloy mused, “indulging in their ... linguistic style, and playing with that, and trying to blur the lines between where Melville ends and I begin."

In the re-imagining, Malloy and director Rachel Chavkin also set out to emulate the sprawling form of "Moby-Dick." The book shifts from first-person narration to in-depth, philosophical digressions on whale art, whale biology and the whaling industry.

“Melville in one chapter just decides to write it as a play,” Chavkin said, “and you're like, 'What was he doing?' And so we wanted to really capture that in this production.”

The almost three-and-a-half-hour experience with live band unfolds in four, highly-choreographed parts. It blends traditional Broadway style with other forms including vaudeville, jazz and hip-hop. Folk-arty, DIY props create a homegrown feel, like community theater with an actual budget.

As in the novel, conventions are broken. The fourth wall between actors and audience erodes. Melville is present much of the time, and is sometimes spoken to and even messed up a bit. But he’s not part of the cast. Instead a faux marble bust stands in for the author.

Malloy made his way through Melville’s 135 chapters in school, but had a revelation when he reread "Moby-Dick" about six years ago.

“I think in college we were very much studying the big weighty themes,” Malloy recalled, “and I had not quite realized that it was like a deeply crude and hilarious novel at times.” He's been running with Melville’s comedy in his new work.

Early in the novel, Melville spent pages setting up a scene where his narrator Ishmael frets when he learns he’ll be sharing a bed with a tattooed harpooner from the South Pacific named Queequeg. In Malloy’s take, the encounter becomes a campy riff on a show tune melody.

Ishmael shouts, “A cannibal!” before belting out, “Well, I don’t want to sleep with a cannibal. I don’t want to sleep with a cannibal. Maybe I’m prude, but it just seems kind of rude, and I don’t want to sleep with a cannibal.” Then the crew chimes in, “No, he don’t want to sleep with a cannibal.”

Turns out the fierce-looking Queequeg, played by Andrew Cristi, is sweet and misunderstood.

“Yes, I’m a cannibal, but not the scary kind,” he croons to Ishmael, and clarifies, “Cannibalism is an outdated term, and it needs to be rethunk I think.” Then Queequeg rattles off the different ways people from cultures around the world consume each other.

The production's immersive set makes the whole theater feel like a ship, and the audience is on the journey, too. A handful of bold folks can sit up front and even board small whaling boats for a whale hunt.

“There is a splash zone that has been advertised,” Chavkin said with a laugh, “and indeed those 20 volunteers will get ponchos and will be involved in processing a variety of fluids.”

In one scene the volunteers sit in circles with the crew and help massage the precious whale oil from a killed and butchered sperm whale’s blubber. It's a sensual act, Chavkin said, inspired by the idea that Melville wrote "Moby-Dick" in a burst of obsessive love for fellow writer and Berkshires neighbor Nathaniel Hawthorne. The book is dedicated to him.

Malloy explained how the accompanying song, “A Squeeze of the Hand,” is extracted from the chapter of the same name and includes ecstatic metaphors beloved by many gay "Moby-Dick" fans.

The crew sings Melville's words in harmony, “I squeezed that sperm ‘til I almost melted in it; I squeezed that sperm 'til I became insane.”

“We've tried to kind of toe that line of, you know, having fun with the double entendre and with the joke of it,” Malloy said, “but also really trying to honor the profound sense of community and belonging.”

Things get much darker as Captain Ahab pushes the Pequod to pursue the elusive, homicidal whale. The musical connects to themes Melville explored in the mid-19th century. It delves into issues including capitalism, the environmental crisis, patriarchy and white supremacy.

"Moby-Dick" was published in 1851 on the brink of the Civil War. The ship represents a microcosm of a diverse and divided country. Melville grappled with the whale’s symbolic, pale flesh in his chapter, “The Whiteness of the Whale.” Chavkin told me the crew is intentionally cast with artists of color, except for Captain Ahab.

“It feels really important that this is the manifestation of the promise of American democracy at its best and its inclusivity. But that still — at the end of the day — is being sort of driven to its doom by an older, white man who is consumed by his own injuries and perceived slights at the world."

Ahab is hell bent on killing the white whale, no matter the cost or sacrifice. His crew becomes expendable.

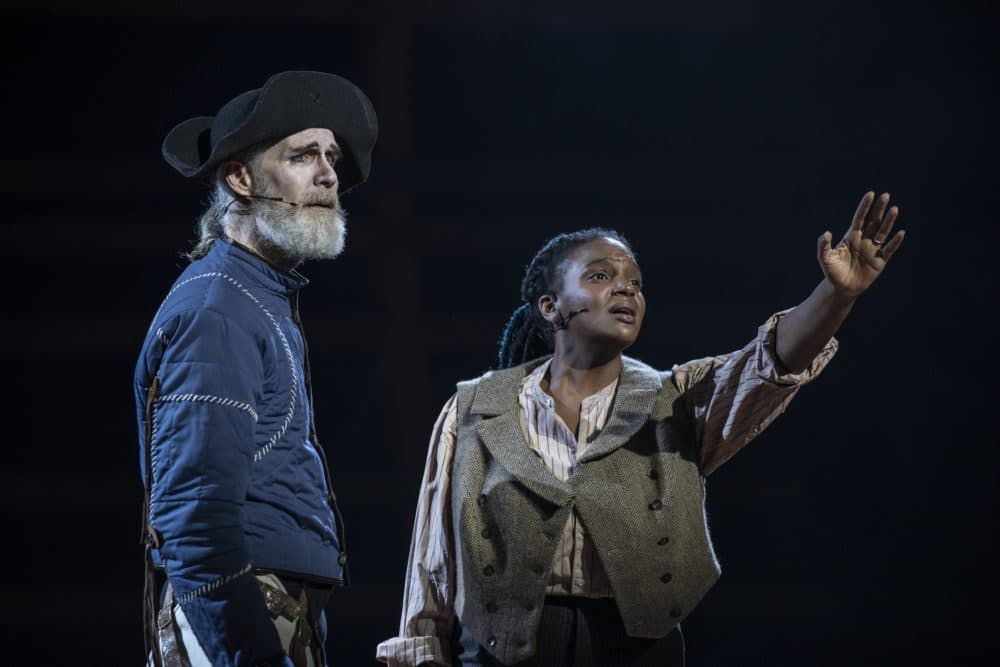

In the book, Ahab’s first mate Starbuck is a white man who questions Ahab’s judgement. Starr Busby plays Starbuck in the musical and she sings a heart-wrenching plea to God for her captain: “That the waters are wide enough, that the voids are vast enough, that he never, never finds what he is looking for.”

As a woman of color, Busby says she draws parallels between Starbuck’s character and her own experience in the United States today.

“Black women, I think a lot of times, are seen as a voice of reason taking notice,” Busby said, “and speaking to something that's incorrect or that isn't working, but kind of still being stuck in this position without enough power to actually change something.”

Busby calls the multi-racial casting "color-conscious." She believes it works because it's meaningful to the musical's story and discourse and that the creators aren't just trying to check off boxes. And she said the production shines a light on America. "We are digging into what that means, and how complicated and nasty and exciting and thrilling that is," she said.

The reverent and irreverent musical also reckons with the idea that "Moby-Dick" is much more than a novel, according to Melville scholar Wyn Kelley who recently saw the adaptation. She’s on MIT’s literature faculty and is a founding member of the Melville Society Cultural Project in New Bedford where Melville himself once set out to sea. For Kelley, watching the musical was like an Easter egg hunt for Melville quotes. She's seen a boatload of adaptations — the films, a play, an opera — and said this new musical captures the author’s spirit.

“A production that goes beyond the limits of what language and narrative can do is completely, it seems to me, consistent with what Melville was doing when he wrote 'Moby-Dick,' ” she said.

But you might be wondering if we need to read "Moby-Dick" to appreciate the musical?

“I hope not,” Kelley replied to the question, “because a lot of people talk about 'Moby-Dick' without having read it. It’s such a part of our culture.”

Who knows, the musical could inspire folks to crack open the hallowed classic — or even to break out into song — as they consider how (as the production's tagline says) we're all in the belly of the whale.

Correction: An earlier version of this story said the musical 'Moby-Dick' connects to themes that Herman Melville explored more than 200 years ago. The book was published in 1851, which was 168 years ago. We regret the error.

This segment aired on December 16, 2019.