Advertisement

Review

Tracing An American Dance Revolution Through The Life Of Ted Shawn

Dream of getting out? How about leaving these past few troubled months behind, traveling to an era when a new style of movement, modern dance, emerged? It was a time when dancers shocked audiences by performing barefoot, their movements free from the confines of ballet, their inspiration gathered in faraway places, from different cultures.

It began more than a century ago, and a new book details some of the origins of this American dance revolution. “Ted Shawn: His Life, Writings, and Dances” by Paul A. Scolieri tells the story of the performer, international cultural explorer, indefatigable missionary of a new brand of movement and founder of Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival.

They called him “Papa” Shawn because he and his wife, Ruth St. Denis, were the “parents” of modern dance. That’s true and not true at the same time.

What’s indisputable is that the two emerged from the vaudeville tradition of entertainment, and founded a school and company known as Denishawn in Los Angeles in 1915. Theirs was a glitzy, theatrical style, with elaborate costumes and sets, that eventually made their artistic progeny — Martha Graham, Doris Humphrey, and Charles Weidman — cringe.

What’s not exactly true is that Shawn was a Papa and Ruth St. Denis a Mama of modern dance. Shawn didn’t even like the term, preferring to call his style “American dance.” And their marriage was no ma-and-pa situation, but an open marriage between two sexually fluid people before there was a name for it. Theirs was a partnership of beliefs. Teaming up together was good for the evolution of their choreographic ideas, and the marriage gave Shawn an identity as the ideal American male. Indeed, a reporter in Akron, Ohio called Shawn the “Most Beautiful Man in the World” (an accolade also given, at the same time, to the Russian ballet dancer Vaslav Nijinsky).

What did Shawn have against “modern dance”? In a series of editorials he wrote for the Boston Herald in 1936, Shawn argued that he had yet to meet a dancer who could explain what the phrase means, as opposed to what it does not mean. “It is not the scarf flutterings of Isadora, not the incense laden orientalism [in vaudeville days] of Ruth St. Denis, not the spectacular stage shows of the Russian ballet.”

Denishawn’s purported mission, writes Scolieri, was “presenting dancing as a serious independent and modern art.”

Beauty was always part of the equation, and Scolieri points out that Shawn used his own body as “…the ultimate specimen of balance, harmony and regulation… [involving] the free expressive use of the body, thus providing the ideal means of embodying music and thus synchronizing the rhythms between mind and body.”

Moreover, Shawn professed that expressive dancing could treat mental disturbances and nervous disorders, hysteria, melancholy and repressed desires. (There’s a great deal in the book about Shawn’s sexual desires, which were anything but repressed.)

Life was not all deep thinking and theorizing about art. Scolieri describes Shawn’s constant worries about funding Denishawn, supplying enough cash to keep the school going, or finishing a road tour. “Everything in my life has been sacrificed to this pioneering work,” Shawn wrote. “I have had no vacations, no recreation, no escape from this all-absorbing task of pioneering in the art dance in America.”

And then there were the delicate sensibilities of the artists to consider. There’s exquisite detail (too much, in fact) about the care and feeding of the dancers, their revolving gallery of lovers, their passions and their moods. A 20-something Martha Graham, feeling underappreciated and unloved, has a tantrum in public. “She grabbed the whole white tablecloth, pulled it off onto the floor, silver, glassware and all, and ran screaming out of the restaurant,” Shawn wrote in his memoirs.

Much as the Denishawn company was celebrated internationally, Shawn describes in his “Reminiscences” interview with John Dougherty in Jan. 1969 the inner struggles as he walked to an English theater with Graham. “Here we are in London, the Strand, Fleet Street, Piccadilly Circus, Westminster, and it doesn’t mean anymore to us than if we were in Coffeyville, Kansas, or Kankakee, Illinois. We were just two miserable souls and we couldn’t have cared less about being in London, and for the first time too.”

Early in life, Shawn had toyed with becoming a clergyman, and Scolieri writes about ways that he incorporated spiritual subjects in his dances. Shawn portrayed religious figures such as “ancient Greek gods and priests, biblical prophets and kings, the Hindu god Siva and even once ‘Atomo’ the god of nuclear energy.”

Shawn’s 50-year career brought to the American stage every archetype of masculinity. Scolieri writes: “In his repertory of ‘ethnic’ dances, he portrayed both cowboys and various types of ‘Indians’ (Osage-Pawnee, Toltec, Hopi, Zuni), Spanish bullfighters, a Muslim dervish, and a Japanese rickshaw coolie.”

During World War I, Shawn enlisted in the military, became a lieutenant, and created benefit performances for the Red Cross, and programs for the troops. He wasn’t impressed with the rigors of training. Shawn was quoted in the Detroit News saying, “You know, the hardest work in the military is child’s play when compared to dancing. In our athletic activities, I have seen 200 men panting and exhausted after dancing around in a circle twice.”

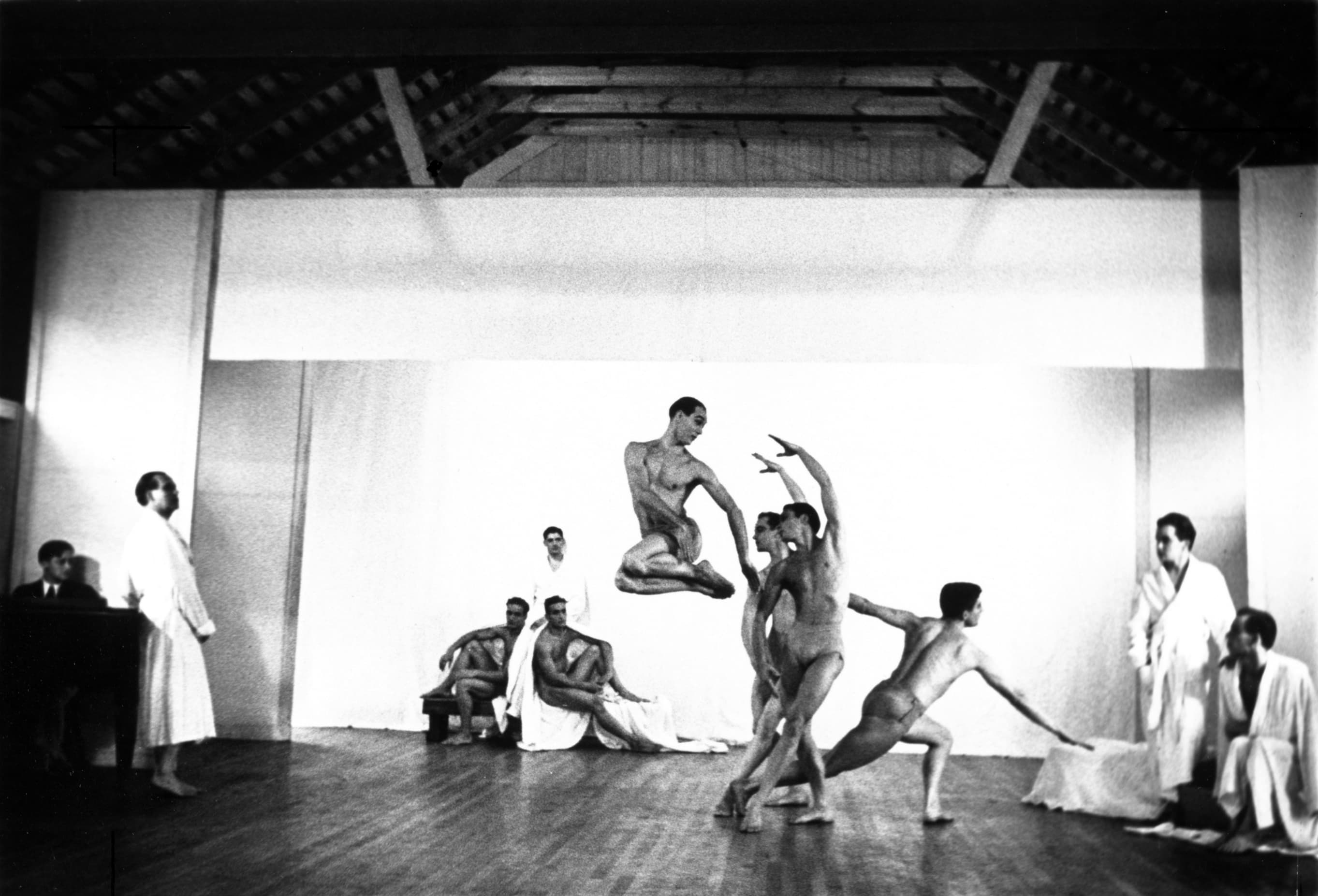

Always battling the homophobia and gender roles of the time and working to convince the public that dance was a legitimate athletic art form for “red-blooded” males, Shawn established his troupe of “Men Dancers” in 1933. The group danced for more than a million people in seven years, giving some 1,250 performances in 750 cities throughout the United States, Canada, Cuba and England.

Scolieri writes about the Boston connection to the first and last days of Shawn’s troupe. “The road for the Men Dancers ended where it all began. On May 6 and 7, 1940, the company performed its final concerts for sold-out crowds at Symphony Hall, just across from the Repertory Theatre in Boston, home to Shawn’s first all-male program in 1933.”

In New England, we’re aware of Jacob’s Pillow but we may have just the fuzziest notions about its origins. We may even recall the three-foot weathervane atop the Ted Shawn Theatre, but not know that it depicts a particular male dancer: Shawn’s best beloved (Shawn addressed him as “Dear BB” to escape the censors) Barton Mumaw, who was in Europe fighting WWII in 1942, when the theater was built.

Scolieri lays out in blow-by-blow detail how the Pillow came to be the dance festival it is today. But while the festival is a legacy of Papa Shawn, in a larger context, he set the stage for the new world of modern dance. Shawn’s was a long and accomplished life, and the story of how, where, and why he danced and choreographed are documented thoroughly in this exhaustive history of a man and his era. This biography can be a heavy and wearying lift, and it could have benefitted from the editing of Shawn’s every meal, conversation and acquaintance. But for stalwart readers interested in dance and culture in general, it’s a deeply-documented 20th-century history of characters who lived courageously, following their passions, always devoted to creating a new art form.