Advertisement

Commentary

During Times Of Stress, Turn To Ambient Music

For all the emotionally wrenching, cathartic rock ‘n’ roll I’ve enjoyed in my lifetime — for all the complex prog, pummeling hard rock and visceral punk — I think the album I’ve listened to most has been Brian Eno’s “Ambient 1: Music for Airports.” Many of his other ambient records have been in the mix, too.

“Music for Airports” must certainly have the fewest cluster of notes and chord progressions of just about any piece of music short of John Cage’s silent “4’33”.” The first side: Percussion-free and mostly piano-based, it drifts and floats in the ether, wordlessly, repetitively, and almost fades into silence. The second side: Soft, gradual waves of synths.

In the liner notes, Eno explained ambient music as “an atmosphere, a tint...designed to induce calm and a space to think.” It should “accommodate many levels of listening attention without enforcing one in particular; it must be as ignorable as it is interesting."

There were no other rules of the game, per se. The album, which was released in 1978, was conceived, in part, as a reaction to and a rejection of Muzak, the ubiquitous, upbeat music that played in the background of many public settings, from malls to dentists offices.

And so, a genre was born. Hundreds of musicians now make ambient music. Eno himself has subsequently recorded at least 10 albums that would fit under the ambient umbrella — most collaborations, some not — and another eight ambient albums made for art installations. (I experienced one of these walk-throughs at the old Institute of Contemporary Art on Boylston Street in 1983. It was called “Mistaken Memories of Mediaeval Manhattan.”)

The key: It’s soft, but not saccharine or schmaltzy. It’s not George Winston and it’s not Yanni. There are many ambient artists to be discovered and, as with any genre, some picks are better than others.

It’s soft, but not saccharine or schmaltzy. It’s not George Winston and it’s not Yanni.

And at this particular time, with everyone suffering in one way or another from the COVID-19 fallout, ambient music may provide even more solace or refuge. Isolation — or at least a lack of social interaction — is where we’re at now. Uncertainty looms. At its best, ambient music supplies a quiet constancy, a tranquility that can counter the disturbing currents running through our brains.

The ambient music Eno made came as something of a shock, albeit a gentle shock, to the system, given what we knew. Eno was an upsetter, an English art school graduate with a flair for crazy-quilt music. He was a flamboyant androgynous synthesist — the sonic doctor — on the first two Roxy Music albums in 1972 and 1973, a proudly self-proclaimed non-musician tweaking their sound, and making it even more other-worldly. Subsequently, on his solo albums, especially the first two, both released in 1974, Eno upended traditional rock ‘n’ roll structure with often chaotic (but catchy), throbbing music. Sometimes ominous, sometimes playful, and rife with clever, albeit absurdist wordplay and unique sonic treatments.

Of note: Although “Airports” is the first album Eno designated as ambient, in 1975 he released "Discreet Music," a soothing, all-instrumental effort which included the half-hour title song plus three variations on Pachelbel’s Canon in D Major.

I talked to Eno in 1992 about the dichotomy between the “rocking” Eno and the “ambient” Eno. He said that “Discreet Music,” contrary to what rock fans might believe, was his best-seller with “Music for Airports” and “Ambient 4: On Land” “coming up the charts.”

"It's thrilling because it so much vindicates the position I took back then,” Eno said at the time. “Everyone said, ‘Well, it's nice, but you can't sell this kind of music. Where do you find it in the shop?’ There was every argument advanced [as to] why this wouldn't be any kind of success."

Exactly. Why would people — especially rock fans and even more especially Eno fans — buy music that was purposefully non-stimulating?

"The ‘rocking’ Eno is not such a successful entity as you would think,” he said, with a laugh. “It's much more visible because its audience is identifiable. Everyone thinks, of course, ‘that's the stuff he made the money from — the other stuff he released because he is a bit of a fruitcake and likes putting out funny records.’ That's sort of what I thought at the time, too, but it turns out history has decided things were a little different and has made it look like the rock records were the hobby."

At its best, ambient music supplies a quiet constancy, a tranquility that can counter the disturbing currents running through our brains.

Eno’s sometimes partner, King Crimson guitarist Robert Fripp, recently re-entered the ambient field. Fripp, throughout his career, has been all over the map, Crimson has been his main vehicle over the years; they played two ferocious sets at Boston’s Boch Center’s Wang Theatre last year. But Fripp has done numerous other projects. In 1979, he played solo at the tiny Passim in Cambridge, with his tape deck-and-guitar setup called Frippertronics. He formed a multi-guitar ensemble called The League of Crafty Guitarists in 1986. He played on Eno’s early solo records and on David Bowie’s “Heroes.”

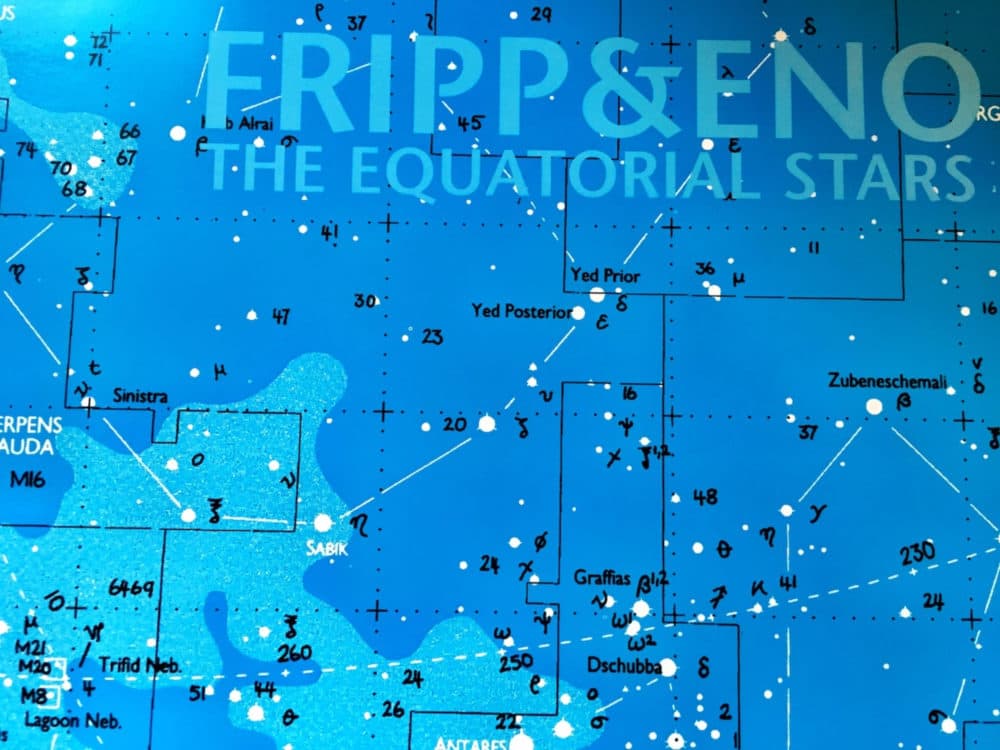

He and Eno began playing instrumental music together with “No Pussyfooting” and “Evening Star” in the mid-1970s and, then, “The Equatorial Stars” in 2004 and “Beyond Even: 1992-2006” in 2007. In this guise, Fripp specializes in treated electric guitar, tape looping and digital processing synthesizers.

Fripp has been a touring musician for 51 years. King Crimson had a summer tour planned, but he, too, is quarantining. So, each Friday, for 50 weeks, Fripp plans to release a piece of music in a series he calls “Music for Quiet Moments.” The series started May 1 with “Pastorale.”

On the King Crimson website, Fripp called the music both “deeply personal; yet utterly impersonal,” adding some compositions “are inward-looking, reflective. Some move outwards, with affirmation. Some go nowhere, simply being where they are.”

A Quiet Moment is how we experience a moment: the moment which is here, now and available. Quiet moments are when we put time aside to be quiet; and also where we find them. Sometimes quiet moments find us. Some places have an indwelling spirit, where quiet is a feature of the space: perhaps natural features in the landscape; perhaps intentionally created, as in a garden; perhaps where a spirit of place has come into being over time, as in an English country churchyard. Quiet may be experienced with sound, and also through sound.

His second offering, which went up May 8, is called “GentleScape.” His third soundscape, a nine-minute-plus segment taken from his 2006 Churchscapes tour, was posted May 15.

Coincidentally, Friday, May 15, was Eno’s 72nd birthday. And Fripp celebrated his 74th the day after. We can assume they were quiet celebrations, but not without a certain grace and subliminal transcendence.