Advertisement

5 Museum Curators Share The Artwork They’ve Missed The Most

For museum curators, life truly does imitate art. These masterpiece maestros are a wellspring of knowledge and tastemakers in the truest sense of the word — illuminating the talents of artists past and present, and sharing their works with the public through carefully crafted collections. With Boston-area museums shuttered since mid-March due to COVID-19, curators are eager to once again immerse themselves in what they love most. As their institutions prepare to reopen in accordance with the third phase of Gov. Charlie Baker’s plan, five art aficionados from local museums share what masterpieces they’re most looking forward to seeing again.

Akili Tommasino

Associate Curator, Modern and Contemporary Art | Museum of Fine Arts

“Suncrush” by Frank Bowling (1976)

Akili Tommasino can pinpoint the exact moment he felt called to become a curator. The Brooklyn, New York native grew up in an apartment adorned with his own father’s paintings and situated a stone’s throw away from cultural institutions like the Brooklyn Museum, but it wasn’t until a summer spent in Italy as a student that he truly confirmed his vocation. On a visit to Florence’s famous Uffizi Gallery, a then 15-year-old Tommasino successfully led his host mother to a Bronzino painting she was eager to show him after she became lost in the museum. “I insisted that we had passed it and she disagreed, but after a few entreaties she let me lead us back to the painting,” says Tommasino, who has been with the MFA since October 2018. “Triumphant, I boasted that I would one day be a museum professional. Little did I know how closely I would adhere to that declaration.”

Just as he so vividly remembers that moment in Florence, Tommasino also recalls the first time he encountered Frank Bowling’s “Suncrush” in the MFA’s offsite storage facility. The abstract painting was acquired in the 1970s during the heyday of color field painting, but not displayed in the museum until October 2019 as part of “Contemporary Art: Five Prepositions” — a collection-based exhibition highlighting work from integral, yet underrepresented artists from 1899 to the present. Tommasino’s office is situated on the opposite end of the museum, and he makes frequent trips to the painting to “bask in its radiance” and ponder the powerful legacy of its painter.

Born in British Guiana (present-day Guyana) and a fixture in the 1960s NYC art scene, Frank Bowling challenged his contemporaries, embracing the technicolor hues and gestural nature of abstract painting when pop art and minimalism ruled the scene. Much of Bowling’s work hearkens to his transatlantic identity — “Suncrush” in particular evokes warmth, vibrancy and the tropical climate of the artist’s homeland — and the large-scale, acrylic-on-canvas work resonates with Tommasino through the parallels he finds between Bowling’s life and his own. “As the son of immigrants from St. Vincent and the Grenadines, raised in Brooklyn, and trained in both Europe and the U.S., I admire Frank Bowling’s intentionally itinerant education, ambitious cultivation of a global perspective and defiance of limitations imposed on Black identities,” he says. “‘Suncrush’ is a vibrant reminder of the tremendous yet often overlooked contributions of people of African descent from South America and the Caribbean to the culture of the United States.”

Diana Greenwald

Assistant Curator of the Collection | Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

“Self-Portrait, Age 23” by Rembrandt Van Rijn (1629)

For Diana Greenwald, growing up in New York City meant frequent trips to the Met. She has fond childhood memories of visits to the iconic institution with her parents to admire the artwork and toss pennies into one of the many fountains — even falling into the water once in the American Wing. “We joke in my family that ever since that fall, it was fate that I become a curator,” says Greenwald, who has been with the Gardner since the fall. “I even specialize in 19th-century American art and was an intern in the very department where that fountain is!”

Despite her penchant for American art, Greenwald is most drawn to a piece by an artist of Dutch descent. Greenwald visited the Gardner for the first time in the summer of 2018 when she was in Boston for a wedding and, despite the beauty of the courtyard and the robust collection of John Singer Sargent masterpieces, she photographed Rembrandt’s “Self-Portrait, Age 23” more than anything else in the museum.

One of nearly 100 self-portraits done by the 17th-century master, the oil painting is one of the artist’s earliest — evident in the soft skin and peach fuzz on his face — and is located in the museum’s Dutch Room. Rembrandt mixes dark and pale hues to create an illusion of light as well as a wide array of tone and texture — both of which are hallmarks of his work. Greenwald’s favorite feature of the painting is the highlight on Rembrandt’s shoulder closest to the viewer. The contrast between the chain and coat as well as how the chain’s color shifts as it moves from illumination to shadow show the artist’s mastery of light.

With a sensitive palette made up of mostly grays, the most minuscule change of light in the gallery will yield a different viewing experience of the painting, which is why Greenwald tries to visit the portrait as much as she can. “Rembrandt's expression conveys a different emotion every time,” says Greenwald. “Sometimes it seems serene; sometimes, confident, and sometimes the artist appears naïve and unprepared for the lifetime ahead of him. Ultimately, this mutability is part of Rembrandt's talent. His self-portraits can reflect a viewer's mood and feelings. This mirror-like function is something I find almost mystical.”

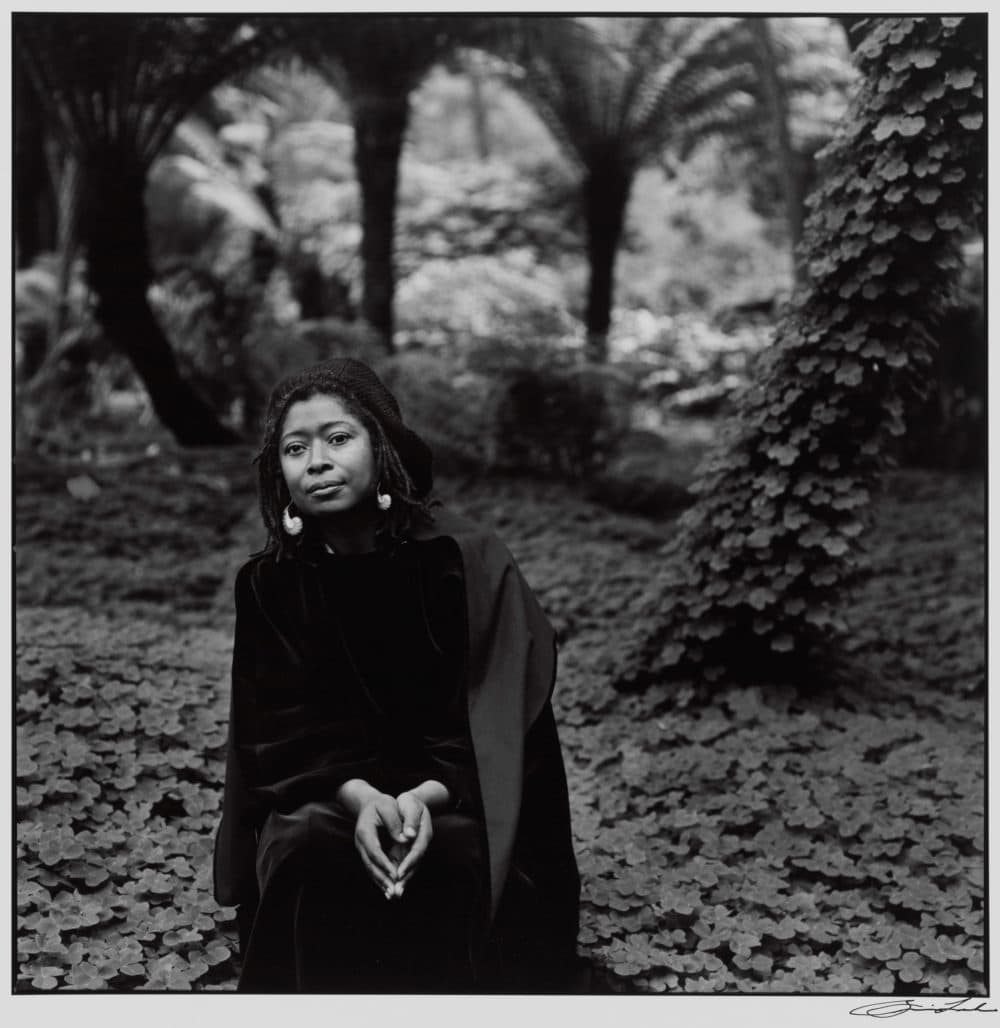

Makeda Best

Curator of Photography | Harvard Art Museums

“I Dream A World” Series by Brian Lanker (1989)

Makeda Best has always been a curator of sorts — collecting images from magazines and postcards and artistically arranging them on her walls beginning at age 11 — but the photography expert first cultivated her passion as a studio artist. After receiving her MFA in photography from the California Institute of the Arts, Best decided to pursue a Ph.D., which brought her to Harvard.

Between her position as a curator of light-sensitive works (which are only on view for up to four months) and her three-and-a-half-year tenure at Harvard Art Museums, Best has ushered an extensive repertoire of exhibitions in and out of the institution’s galleries. But this relatively short time interacting with each collection doesn’t make them any less meaningful to the curator — especially in the case of Brian Lanker’s “I Dream A World” series.

An award-winning photojournalist for publications such as Life magazine and Sports Illustrated, Lanker captured powerful portraits of some of the most influential African American women of our time in this series. This collection is one influence that inspired Best to be a photographer and spawned her own portrait series commenting on race in America after seeing the collection on display at the Oakland Museum of California in 1991. “The catalog was the first book of photography that I ever owned,” says Best. “I remember as a teenager looking at these portraits thinking about what these women faced, the wisdom their lives offered, and wondering about what they envisioned for my generation…I still look at these works and am enthralled by their intimacy, by the faces, and by the eyes.”

Beyond the photographs themselves, Best also misses the experiential elements of interacting with the collections, such as the dialogue the photographs create when they are presented alongside other objects. For example, a group of photographs by Ian Van Coller depicting African design and architecture from iconic monuments to private spaces complement a nearby lintel salvaged from a region that’s part of a collection of Islamic art.

Despite the multitude of artwork she has showcased over the course of her career, the works she first collected by postcard will always hold a special place — such as Chester Higgens Jr.’s “Coffee Counter in Harlem, 1977,” which she recently acquired for Harvard. Best says, “It was amazing to meet Chester and to look with him at this image that had inspired me as a young person to think about photography.”

Amanda Gilvin

Senior Curator of Collections and Assistant Director of Curatorial Affairs | Davis Museum at Wellesley College

“A Tisket” by June Edmonds (2019)

Drawn to a career in art history through her work with glass, jewelry and textiles, Amanda Gilvin set out to explore the division between what is considered art and what is categorized as craft in material culture. The art expert studied bead-making as an undergraduate at Kenyon College in Ohio before pursuing an M.A. in Africana Studies at Cornell University. While studying at Cornell, Gilvin realized that delving into the history and visual culture behind African art sparked new questions and curiosities about the medium, which led her to complete a doctorate in the history of art and visual studies at the university. “I love being a curator because of the focus on studying artworks in person and the opportunities for working with artists,” says Gilvin, who has been with the Davis since 2016.

With the museum closed due to the current public health crisis, Gilvin hasn’t had the opportunity to admire the masterpieces at the Davis firsthand for months now, and the piece she misses seeing the most is one that she was only just starting to get to know. June Edmond’s “A Tisket” was acquired by the Davis last year and has only been hanging in the institution’s light-filled fifth floor contemporary gallery since August 2019. The acrylic-on-canvas piece is dynamic not only in color, but also technique. Edmond’s distinctive style of impasto encapsulates a plethora of formal and conceptual references to other art forms, such as textile, architecture and music.

An American painter based in Los Angeles, Edmonds has described her work as a “doorway to memory,” which is evident in the many allusions to longstanding African traditions and influential African Americans from bygone eras. The piece’s name references jazz musician Ella Fitzgerald’s 1942 hit, while the arcs and concentric circles the artist incorporates speak to a symbol found on Adinkra cloth — a hand-printed Ghanaian textile crafted in the 1930s and 1940s — representing charisma and leadership. “The bending lines of contrasting colors lead your eye around the painting, and in person, the texture invites a close look,” says Gilvin. “It intrigues me because of the almost dizzying experience of studying it, and because of its conceptual and formal conversations with other artworks.” Gilvin also cites the interest Edmonds generates by adding interruptions to the patterns, such as the small blue line down the center and the red line tracing the edge of the painting, guiding the viewer’s eyes.

Not only do the piece’s abstract shapes spark contemplation about the shifting and intersecting nature of history, but it also fosters integral introspection around present-day issues. Gilvin says Edmonds’ “investigation of African and African Diasporic memory resonates with the urgent calls from Black Lives Matter activists to end the anti-Black racism that has shaped human history.”

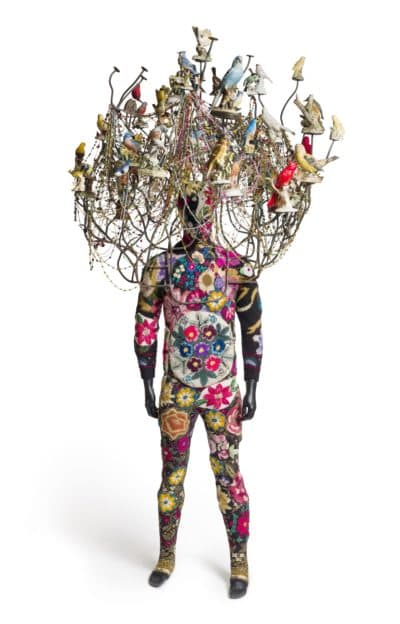

Anni Pullagura

Curatorial Assistant | Institute of Contemporary Art

“Soundsuit” by Nick Cave (2009)

Despite her training in art history, Anni Pullagura made the decision to pursue curatorial work based on her interest in museums themselves. The former ICA curatorial fellow is just as curious about the collection, preservation and exhibition of works as she is the art itself — emphasizing the importance of protecting and advocating for artists. “We know that this impulse to collect the world is a very fraught one, for the history of museums is deeply connected to the history and present, of settler colonialism, extractive resource industries and the persistence of social inequities,” says Pullagura, who has been a curatorial assistant at the ICA since January. “As an arts worker in museums, I don’t want to deny that history. I think it’s important to recognize and be conscious of this impulse, and even to rethink how museums must redress this past and commit to more just futures.”

Pullagura carries that same social sensitivity and sensibility when it comes to what works of art move her — such as Nick Cave’s 2009 “Soundsuit,” a mixed-media sculpture that’s one of hundreds of iterations, each designed to protect the body like a second skin. Cave’s series of suits was created in response to the violence enacted against Rodney King in 1991 and explores the artist’s own identity as a Black man, as he builds sculptures from “discarded” objects that reflect the way he feels viewed by society.

The life-sized piece of art — part of the exhibition “Beyond Infinity: Contemporary Art after Kusama” — is decked out with exquisite colors and an intricate floral pattern, and yields a new viewing experience each time one observes it, which is why Pullagura stops by the work whenever she can. “‘Soundsuit’ really rewards careful, slow looking,” says the curator. “It asks you to be still and consider itself on its own terms, and insists on a form of respectful witnessing and contemplation that feels quite mutually nurturing, as though bearing witness to the work is a form of care to the art object and to ourselves as visitors before it.”

Out of all the visually compelling elements that make up the sculpture, Pullagura is most captivated by the chandelier-like headpiece that veils the figure. The crown is adorned with nesting birds that look at once restful and protective — as if they’ve made the body their home. She also notes the dichotomy between how the headpiece conceals the figure but also draws attention with its boldness. Hoping the piece will spark joy and reflection in others once the ICA opens its doors again, Pullagura says, “This balance of vulnerability and protection feels central to an ethics of care that preserves and celebrates life as something that should never be discarded or insignificant.”