Advertisement

New Documentary Highlights Enduring Activism Of Singer Harry Chapin

“I’m not sure of an afterlife,” Harry Chapin said, “but what we can do is maximize what we have in this brief flicker of time in the infinity and try and milk that.”

It’s a telling line from “Harry Chapin: When In Doubt, Do Something,” a 93-minute documentary directed and co-produced by Rick Korn, now playing at the Landmark Kendall Square Cinema in Cambridge and virtual cinemas.

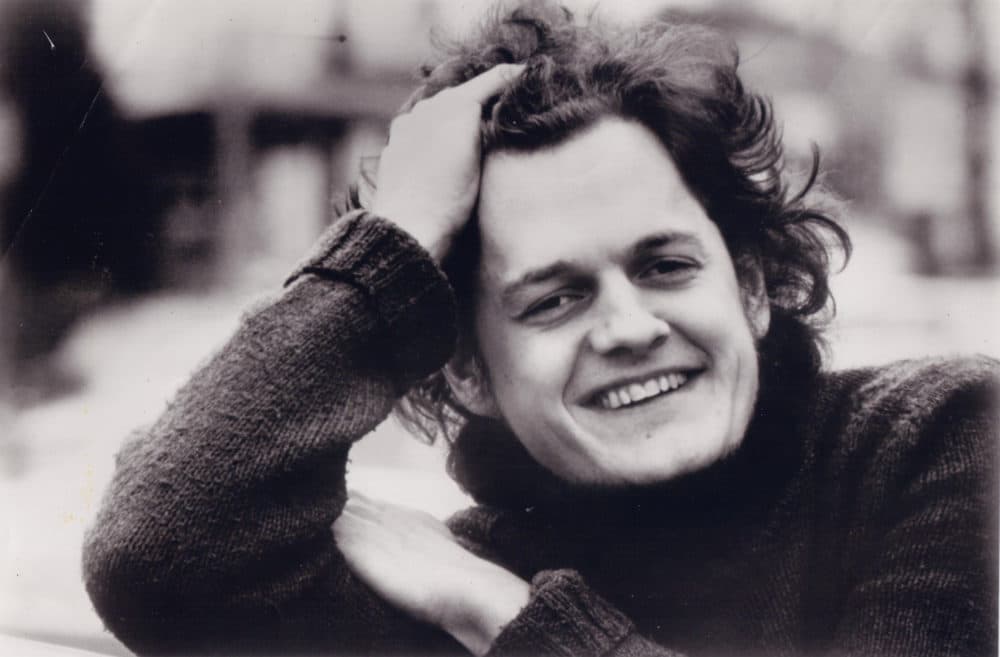

In the early to mid-1970s, Chapin had big Top 40 hits — ballads like “Taxi” and “Cat’s in the Cradle” — and over his decade of music-making, he sold over 16 million records. He had a certain cachet in the folk/soft-rock world, up there with Cat Stevens, John Denver and Gordon Lightfoot.

But Chapin was never what you could call hip. Except, perhaps, in one particular community: Singer-songwriter-activists. And that wasn’t exactly a huge group back then.

Chapin was in Boston in June of 1981 to check out a preview performance of a gently satirical musical he wrote called “Somethin’s Brewin’ in Gainesville,” later renamed “Cotton Patch Gospel.” It was a folksy New Testament rewrite, set in the Bible Belt, asking the question: “What if Jesus were born 40 years ago in Gainesville, Georgia?"

On this night, Chapin and I were having dinner at a Chinese restaurant after the play. Chapin was on fire. The talk turned to how ticked off he was at Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority, the "lack of concern for women" shown by some organized churches, and the bogus selling of salvation over the airwaves. "I am incensed," he said, "by the misuse of religion, to have Jesus's words so blatantly misused and used as a cover for un-Christian attitudes."

Before Bono, before Sting, before Don Henley, before Live Aid and Farm Aid, there was Chapin.

The 38-year-old musician did not write much protest music himself, but he was working on a conceptual album, "The Last Protest Singer.” Its theme, Chapin told me at the time, was "what it's like to be a musician and a man of conscience as society goes amok."

Chapin was that, too, of course. He was also, very much, a man of action. Before Bono, before Sting, before Don Henley, before Live Aid and Farm Aid, there was Chapin. In 1975, when he was 33, he cofounded WHY (which stood for World Hunger Year) with ABC Radio host Bill Ayers. (It is now called WhyHunger and Ayres is still on the board and serves as ambassador.)

It’s one of the prime focuses of “Harry Chapin: When In Doubt, Do Something.” The movie’s title comes from Chapin’s motto; Chapin’s commitment to causes — not just world hunger, but many others — came from an almost manic devotion to matter, to make a difference beyond the scope of his music.

He wasn’t lacking for ego, nor self-deprecating wit. At one point in our interview, he described himself as “the most socially and politically committed performer," and in the next breath added, "That's not saying much.”

Chapin wasn’t unique in being a musician/public figure who burned the candle at both ends. But his ends weren’t all-night booze-and-drug binges and then getting up to play music. Chapin’s behavior was rooted in altruism and he set an inexhaustible pace for himself, racing from benefit to benefit — nearly half his concerts were benefits — meeting with grassroots folks and politicians alike. Chapin lobbied Congress and President Jimmy Carter. In 1977, he helped create the Presidential Commission on World Hunger.

“Harry was right as he was right about many things,” Bob Geldof, the co-founder of Live Aid, says in the doc. “There’s no need for hunger. … [But] he lobbied too nicely in Congress. Those f---ers are up for election every two years — take them out.”

“Cat’s in the Cradle,” as the film points out, became a cross-cultural reference point over the years — popping up in numerous TV series from “The Simpsons” to “The Office.

It’s about a hard-working dad with little time for his young son; over the years, the roles reverse and the retired dad aches for his adult son to visit. The son sends his best, but is too busy, the father realizing, “He’d grown up just like me.”

Did it pertain to Harry? Quite possibly. He wrote the music, but his wife Sandy wrote the lyrics. “He was very attentive to his kids when he was around,” Korn says, on the phone. The Chapin family — he had five children — went on vacations, “but even on vacation he was working on hunger issues or writing a song.”

"He was very attentive to his kids when he was around, but even on vacation he was working on hunger issues or writing a song."

Rick Korn

In the film, Bruce Springsteen talks from the stage, joking how when he and Chapin were recording in the same studio complex, he’d try and dodge him because even a casual chat with Harry was a half-hour affair. Chapin told him he’d play one night for himself and the next for charity. “Not being bent to extremism, I wasn’t as generous as he was,” Springsteen says, but adding Chapin’s activism-fundraising pushed him in that direction.

The film crew had access to loads of material, not just concert shots and fund-raising events. Chapin’s uncle, Richard Leacock, had been a documentarian filmmaker and, it turned out, had shot lots of footage of Chapin’s family when he and his brothers were growing up. “It had been sitting in a barn in Andover, New Jersey for 55 years,” says Korn. “No one knew it was even there. His son, David, said ‘I know Dad’s got some stuff in there’ and the first box he went to had that tape of Harry.”

Chapin’s forte was the story-song. The length made them unfriendly to AM Top 40 radio, but the melodies and pathos of the songs made them rule-breaking hits. “The thing I learned most about Harry’s music in doing this film is, because of his filmmaking background, he wrote songs the way we write films,” Korn says. (Chapin was nominated for an Academy Award for his 1968 doc “Legendary Champions.”) “There’s a beginning, middle and end and you’ve really got to develop the characters. That’s why his songs were so long; they were mini-movies.”

Over that dinner back in 1981, Chapin poked a little fun at himself, saying he was "the only [songwriter] dumb enough to be using the extended narrative form." Which is to say, it could be a hard sell.

By the early ‘80s, Korn says, Chapin was not well-liked within the music business. “Not by his fellow artists, but the industry,” says Korn. “[They said] ‘Make up your mind. Either you’re in the music industry or you’re a politician.’ He didn’t want to be a politician; he was an activist.”

But the dual roles were causing friction within the Chapin camp, too. There was a strain on the marriage. And in the film, Chapin says, “I’m a man who generates about $2.5 million every year and I’m broke.” On July 15, 1981, he was supposed to meet with his agent and his half-brother/co-manager Jeb Hart about restructuring the balance between music and charitable concerns. He missed the meeting.

“All this frenetic energy and charity work took focus off the concrete planning and maintenance of the career which leverages it all,” says Hart in the film.

"He didn’t want to be a politician; he was an activist."

Rick Korn

“They were going to read him the riot act because everyone at that point was frustrated with Harry,” says Korn. “It was after [Jimmy] Carter lost in 1980. He started to double his efforts and it was already crazy before that. He was running on all cylinders.”

The next day — just over a month after our Boston interview — Chapin was on his way to that rescheduled meeting, after which he would play a show on Long Island at Eisenhower Park. His VW Rabbit was having mechanical trouble and Chapin was on the Long Island Expressway. He pulled into the right lane, slowing down. He was rear-ended by a truck, the car bursting into flames. The truck driver stopped and pulled him out, but Chapin was dead.

In 1986, Chapin was posthumously awarded the President’s Merit Award at the Grammys and in 2011 he was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame. The charitable organizations he co-founded live on. A portion of the film’s proceeds will go to WhyHunger and The Harry Chapin Foundation.

“Harry Chapin: When In Doubt, Do Something” is now playing at the Landmark Kendall Square Cinema and virtual cinemas.