Advertisement

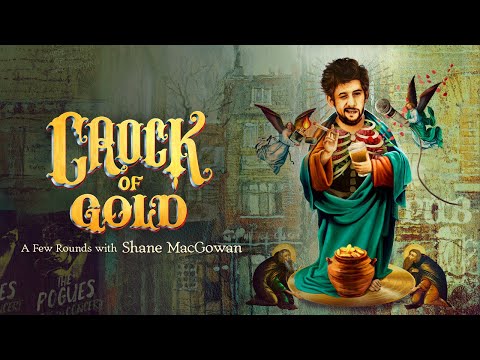

Documentary 'Crock Of Gold' Taps Into The Chaotic World Of The Pogues' Shane MacGowan

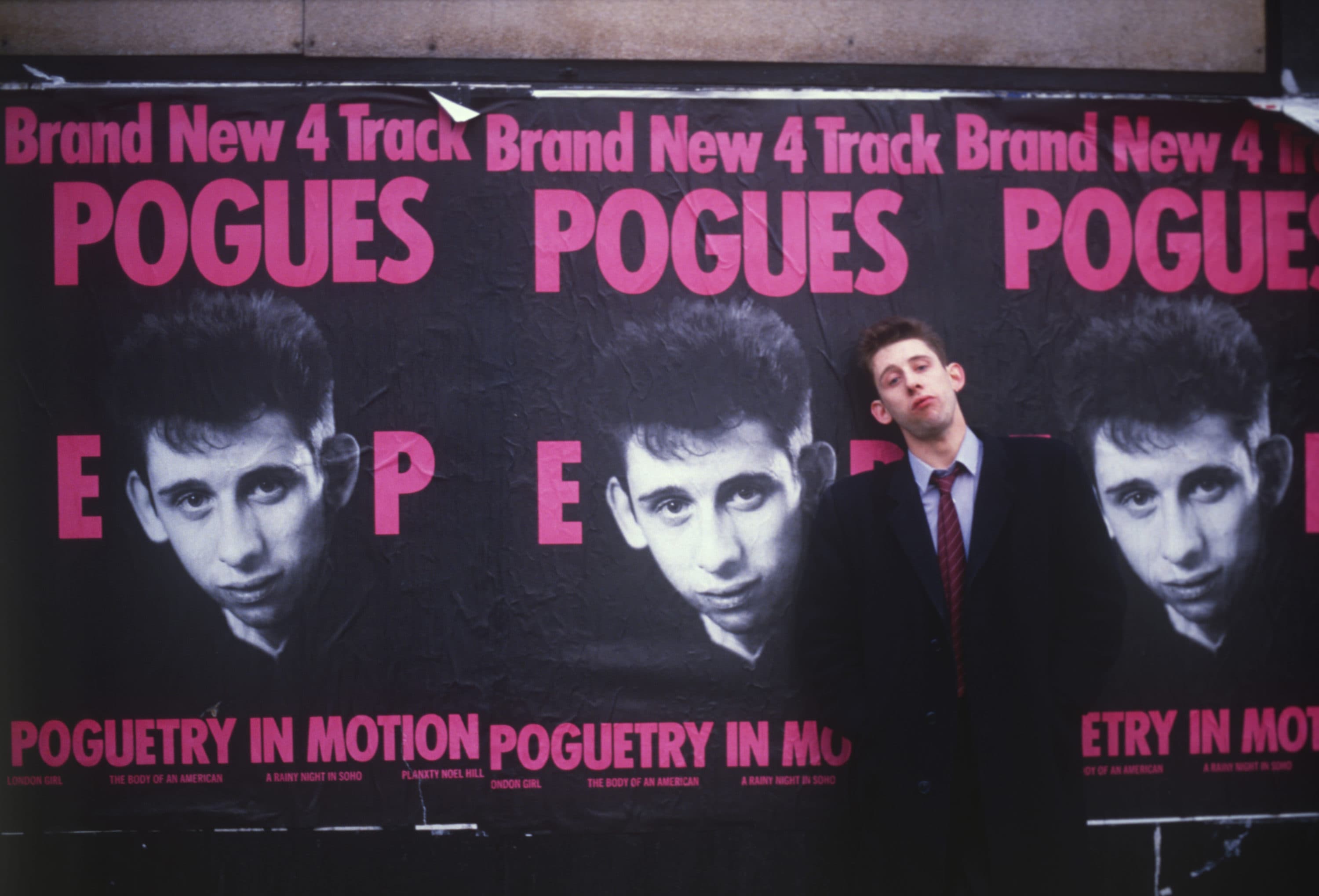

It was a radical idea in 1984: A London band fusing the acoustic lilt and emotional heft of traditional Irish music with the ferocity and aggression of punk rock.

It sprang from the mind of singer-songwriter Shane MacGowan, who’d briefly fronted a middling punk group called The Nipple Erectors. He found his true calling with the Pogues — a sextet featuring banjo, mandolin, acoustic guitar, accordion, tin whistle, bass and drums. MacGowan sussed out the increasing popularity of world music and thought Celtic music had a place on the scene. “We’ve got our own indigenous music on our doorstep, the Irish diaspora in London,” he says in “Crock of Gold: A Few Rounds with Shane MacGowan,” a new documentary by Julien Temple streaming at The Brattle’s Virtual Screening Room and on multiple video platforms.

MacGowan’s first Pogues song was “Streams of Whiskey” in which he fantasizes about hanging with the late Irish novelist-poet Brendan Behan. When the chorus kicks in, MacGowan barks, “I am going, I am going, any which way the wind may be blowing/ I am going, I am going, where streams of whiskey are flowing!” It was an acoustic-powered adrenaline rush, a “happy” song about the drinking and carousing life — a song of curses and camaraderie, of bloodshed and jail. An entrée to Pogues-land.

Many viewed MacGowan as the Behan of his generation – a brilliant artist who has struggled with alcohol and created much joy and caused considerable damage, much of it self-inflicted. It’s that world that English rock 'n' roll documentarian Temple — who’s done films on the Sex Pistols and The Clash’s Joe Strummer — explores in this work.

MacGowan’s songs often coursed along an embittered, defiant, spirited track. He expressed the tangled-up impulses of futility and hope as well as anyone. He lived; he loved; he fought; he drank. He screwed up. He rose the next day to do it all again. Or his characters did. The lines were blurry. It's those blurry lines Temple’s film vividly explores.

“The original Pogues lineup was very good and we were pissed [drunk] every night when we were on stage,” reflects MacGowan at one point in the film. “Actually, we’re better when we’re sober but it’s not as much fun so we get drunk.”

If you’re wondering — and you should be — yes, there are subtitles whenever MacGowan, who turns 63 on Christmas, speaks. At his most sober, he’s difficult to understand, what with his heavy accent, his missing teeth and his disconcerting hiss of a laugh spurting up at odd moments.

Though born in England, MacGowan spent his early years on a farm in Ireland’s County Tipperary, with an aunt giving him his first stout at age five. He was surrounded by traditional Irish music and Catholicism and was fine with both. The religious affection because he loved the beauty of the Mass, but moreover, was told that in heaven you got booze and cigarettes. Early on, he had an inkling of who he might become: “God said I’m the little boy he’s going to use to save Irish music and take it to greater popularity than it’s ever had before.”

There’s a key question buried deep in Temple’s doc. A TV interviewer — someone who’s known MacGowan for years — bestows rapturous praise upon MacGowan’s artistry and asks, “How can you do it when you appear to be on the edge of falling over all the time?”

“Well, I’m sitting down at the moment,” MacGowan answers, cheekily. “It’s true that I am out of it most of the time, but I can write songs when I’m out of it. In fact, it’s easier to write songs when I’m out of it.”

At another point, he explains, “I’m just following the Irish way of life: Cram as much pleasure as you can in your life and rile against the pain that you have to suffer as a result and then wait for it to be taken away with beautiful pleasure.”

Of course, you wonder if MacGowan is a reliable narrator. The best answer I’ve got? Maybe. I don’t doubt that it’s his truth, rolled out at varying points over his lifetime.

The film follows a mostly chronological, if zigzagging, path. The narrative is well-served by home movies, recreated black-and-white scenes and, especially, by Ralph Steadman’s garish, oft-hallucinatory animation (think reenvisioned childhood beat-downs and drug trips).

Everything shifted when the family relocated to London. Shane was six and he found himself anxious, depressed and paranoid, friendless and beaten up by the English kids for being a “Paddy.” Later, as a teen, he won a literary prize from the Daily Mirror, got kicked out of school for dealing drugs, worked as a laborer, earned cash as a “rent boy” (or sex worker) and was institutionalized for the first time.

But his hatred for London, he says, turned to love/hate: “I loved the drugs, the drinks, the parties, the gigs, the girls — the only point in being here is the nightlife.” He also found London was flooded with Irish immigrants and he found his tribe. MacGowan dug the Sex Pistols — he’s seen pogoing in the crowd at an early gig — and says, “Punk is the best thing that ever happened to me. Going to see the Sex Pistols changed my f---ing life.”

There are many archival concert clips and interviews. There are three main contemporary interviewers — his longtime friend and film co-producer Johnny Depp, MacGowan’s wife Victoria Mary Clarke and Irish politician Gerry Adams, the former president of the Sinn Féin political party and a Pogues fan. Adams praises MacGowan’s songs of redemption and sorrow telling the singer, “You deepened our culture. You made us sad, you made us happy, you made us reflect.” (MacGowan was pro-Irish Republican Army, and in the movie castigates himself for not having the courage to join, and instead channeling his rage into song.)

We often see the present-day MacGowan with his head slumped at a 45-degree angle, his eyes glassy. He’s been in a wheelchair for five years, following a nasty fall in a studio. Near the end of the two-hour film, he tells Adams, “I’ve run out of inspiration at the moment.” MacGowan’s goal, he tells his wife, is just to get his “balance of walking back.”

The Pogues commercial high point, certainly in retrospect, was “Fairytale of New York.” It’s gorgeous and elegiac, but harsh — the guy (MacGowan) and his girlfriend (guest singer, the late Kirsty MacColl) angrily break up on Christmas Eve and hurl vile accusations at each other, their life a debris field of broken dreams.

“It was a happy time for the group,” MacGowan tells Adams. “It was our ‘Bohemian Rhapsody.’” Later, though, he tells Clarke, “I don’t want to write anything like ‘Fairytale of New York’ [again].” Asked why not, he answers, “Because I hate it.” And he’s soon autographing a copy with an expletive.

The Pogues sacked MacGowan in 1991 for chronic misbehavior, including missed gigs. He was told during a group meeting. “I thought, ‘Oh, is that all? That’s great, what took you so long?’” recalls MacGowan. “It felt like a lead weight had been taken off my shoulders. I felt like I was floating on air.”

MacGowan was angry that others had taken over a big chunk of the songwriting and had veered the band away from its Celtic roots. “I only started f---ing up when I started hating what we were doing,” he says.

MacGowan took a few years off and got his own backing band together, The Popes, which put him back in his musical comfort zone: “They’re my backing band, I write the music and they play it really well.”

The doc concludes with MacGowan’s 60th birthday party, held in Dublin at the National Concert Hall, with Bono, Nick Cave, Sinéad O’Connor and others singing his songs with some of the Pogues in the band. MacGowan, in a wheelchair pushed by Clarke, comes on at the end and sings a bit. It’s a celebration and, yet, not.

“Crock of Gold: A Few Rounds with Shane MacGowan” is streaming in The Brattle’s Virtual Screening Room and is also available on Apple TV, Google Play, Fandango and Amazon Prime Video.