Advertisement

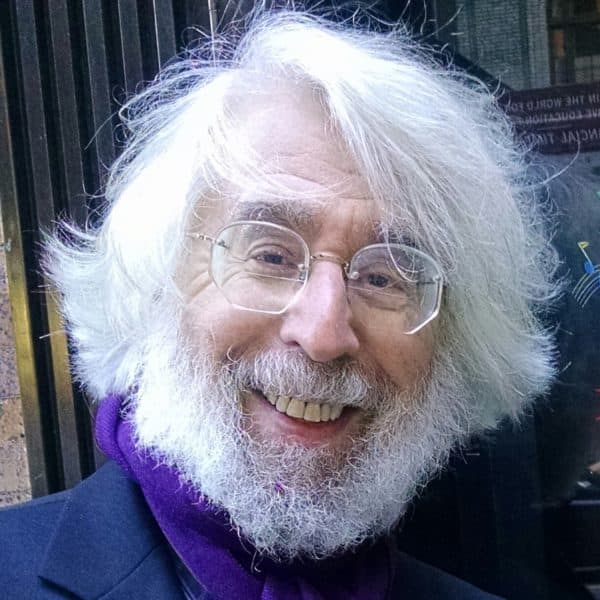

Composer Yehudi Wyner Joins BSO Violinist Wendy Putnam In Virtual Chamber Music Concert

Last year wasn’t great for live concerts — practically all classical music went virtual. And although I’d rather hear music in person, I was also grateful to hear some wonderful music-making digitally. One of the best concerts I heard all year was a “Conversation and Concert” presented by the Concord Chamber Music Society, with the revered composer-pianist Yehudi Wyner and Boston Symphony Orchestra violinist Wendy Putnam, the founder and director of CCMS, which is now celebrating its 20th anniversary. Recorded last September at GBH’s Fraser Performance Studio, with GBH producer Brian McCreath serving as host and moderator, it was released near the end of December, which is when I saw it. And now, I’m happy to say, it will be having a new lease on life.

This memorable concert is about to resurface divided into three weekly 15 to 20-minute segments premiering on YouTube, each of which will include both the “concert” and the “conversation.” Immediately following the first screening of each part, Putnam will hold a live Q&A with the audience.

The concert includes four short but rich “occasional” pieces by Wyner himself, spanning his career from 1961 to 2020, plus a delicious concert piece by the increasingly rediscovered African American composer Florence Price (1887-1953), who was once a student at the New England Conservatory—one of the few music schools in the early 20th century that admitted musicians of color. And Schubert’s heavenly Sonatina No. 1.

Interspersed with the music are McCreath’s lively, intelligent discussions with Wyner and Putnam.

The first pieces, both for solo piano, are Wyner’s “Piccola Fantasia Davenniana” (1966) and “4 x 20” (2020). McCreath asked Wyner to explain the word “Davenniana.” Wyner confesses that he had been “courting” the illustrious pianist and educator Ward Davenny’s “glamorous, beautiful, intelligent, talented” daughter (the illustrious soprano and conductor Susan Davenny Wyner, now Wyner’s wife of many years). “I was trying to charm the father into believing I was a worthy suitor.” Though only a few minutes long, the piece has astonishing variety and is one of Wyner’s rare pieces with a tone row — a repeated series of notes, what he calls a “shaped scale,” here based on the letters in Ward Davenny’s name.

The piece “4 x 20” was occasioned by Bach scholar Christoph Wolff’s 80th birthday last year. Only a hair over a minute long, it includes a total of 20 bars, each bar having four beats (hence the title). “I didn’t plan this as a mathematician,” Wyner says. The music is of otherworldly delicacy, as is Wyner’s playing.

Wyner tells McCreath that, being the firstborn in a musical family (his father, Lazar Wyner, was one of the foremost composers of Jewish music; his mother a Juilliard graduate), he was “programmed to be a musician,” and was expected to be a concert pianist. “It was not a happy experience. I was no prodigy.” Yet he is an extraordinarily “musical” pianist, still performs, and is closely associated with keyboard music. He was awarded the 2006 Pulitzer Prize for his exhilarating and mesmerizing piano concerto, “Chiavi in Mano” (Italian for “keys in the hand”), commissioned and premiered by the BSO.

Wyner is then joined by Putnam for his “Three Informal Pieces” (1961), a work with a complicated history. Written under seemingly ideal circumstances, in a beautiful converted mill in Connecticut, it was a commission that gave the composer little joy. He complained to his neighbor, the elder composer Henry Cowell, that he hated this deadline. “Yehudi,” Wyner reports Cowell telling him, “there’s nothing in life more important than a deadline.” After its first performance, he “put it to sleep for eight years.”

Now he acknowledges that his discomfort with the music was that it may have been “too revealing about myself — a very vulnerable, troubled guy.” When he later resurrected it, he began to understand what made him uneasy. In the early ‘60s, what was fashionable in music was “pre-compositional planning,” but he had really needed to write “something more spontaneous, more liberated to the imagination.” He now compares himself to novelists, who don’t necessarily know where the story is going but who start with a character. “A lot of creation is improvisatory, which then becomes increasingly organized.”

Hence the title, three “informal” pieces, which turn on a dime. And both Wyner and Putnam turn on the same dime, shifting like quicksilver between the spikey and the dreamy, the ending of each movement coming as a surprise, unexpected yet inevitable. They are an ideally suited team — unshowy, but full-hearted players, with a deep eloquence, a respect for beauty of tone but not for its own sake, and a palpable respect for the music and for one another.

“I love these pieces,” Putnam tells Wyner. “They’re so personal. It’s a privilege to play them in front of you.”

“What more can a composer ask?” Wyner replies. “I’m not trying to please an audience. I’m trying to reach another soul.”

The next duet is Florence’s Price’s soulful “Andante con Espressione,” an achingly romantic interlude to which both players give themselves entirely. Not surprising that it’s the featured work on the video preview:

One of the highlights of the “Conversation” element of this concert is Wyner’s reminiscence of the legendary Paul Hindemith. He had gone to Yale to study with Hindemith, but Hindemith refused to work with undergraduates. But by the time Wyner was a graduate student and finally worked with the master, “the romance was gone. I went into the Stravinsky camp.” Hindemith and Stravinsky were more rivals than friends. Hindemith told Wyner that “when he would be in a room with Stravinsky, Stravinsky took up all the air.”

The last duet for Wyner and Putnam is the enchanting Schubert Sonatina, Putnam talks about the way the composer was already beginning to look forward to the longer melodies of the later symphonies, “backbreaking” works, she says, for orchestral players. But “you can hear the young Schubert thinking ahead… harmonies that are so shockingly beautiful!” The performance is sublime.

Wyner mentions that the musicologist Alfred Einstein thought Schubert’s sonatinas were also “occasional” — that is, not “casual” but serious music composed for an occasion, like someone’s birthday. And that was what for him connected all the pieces on this program.

McCreath asked Wyner what he learned from the great composers of the past. Wyner calls it “intuitive absorption”: “I don’t learn from studying scores. I learn from playing and listening.”

The “Concert and Conversation” ends with another short “occasional” piano solo, almost an encore—Wyner’s brief “Three-Fingered Don” (1993), his “send-off” gift for composer and clarinetist Donald Martino, on the occasion of his retirement from Harvard. He talks about Martino’s attempt to write Tin-Pan Alley” songs, which he played with only three fingers (which Wyner slyly imitates). The piece is both jazzy and touching, and full of affection—a perfect ending to a perfect concert.

I hope everyone who loves music will want to watch it.

The three upcoming segments will stream on Feb. 12, Feb. 19 and Feb. 26. All programs will be available at noon and will be followed by a live Q&A with Wendy Putnam.