Advertisement

Biotech's 'Ultra Long-Lasting' Capsule May Help Combat Malaria, Boost Drug Adherence

An oral capsule that unfolds into a star shape in the stomach to deliver medicine for two weeks may boost malaria-eradication efforts and also help patients manage diseases that require strict drug adherence.

The novel drug delivery system is the latest venture led by MIT professor Robert Langer, the prolific inventor, with doctors from Brigham and Women's Hospital and others from around the world. In a new paper, researchers report that tests on pigs suggest the new "ultra long-lasting'" drug capsule could greatly enhance global malaria elimination programs and also help a range of patients — with Alzheimer's disease, psychiatric illnesses, diabetes, HIV — more easily stick to their medication regimens.

Cambridge-based biotech Lyndra, which has licensed the technology, says human trials using the drug capsule should begin next year. Amy Schulman, Lyndra's cofounder and chief executive officer, says if the product is approved by regulators, it could be on the market by 2021.

"Why is this important?" says Langer, who has launched more than 30 startups, developing new technology and products ranging from immunotherapies and vaccines to shampoo. "People don't take their medicines and this might be a way, someday, for Alzheimer's patients to have much better treatments and people with mental health diseases to have much better treatments."

He said the initial focus on malaria was initiated to try to fix a global health problem: "Could we help malaria patients, could we actually eradicate malaria by doing this?"

There are several unique elements of the device, researchers say: While it can reside in the stomach for two weeks slowly releasing a steady dose of medication, its star-shape protects it from the gut's acidic environment. After use, they report, the capsule breaks down and passes through the gastrointestinal tract.

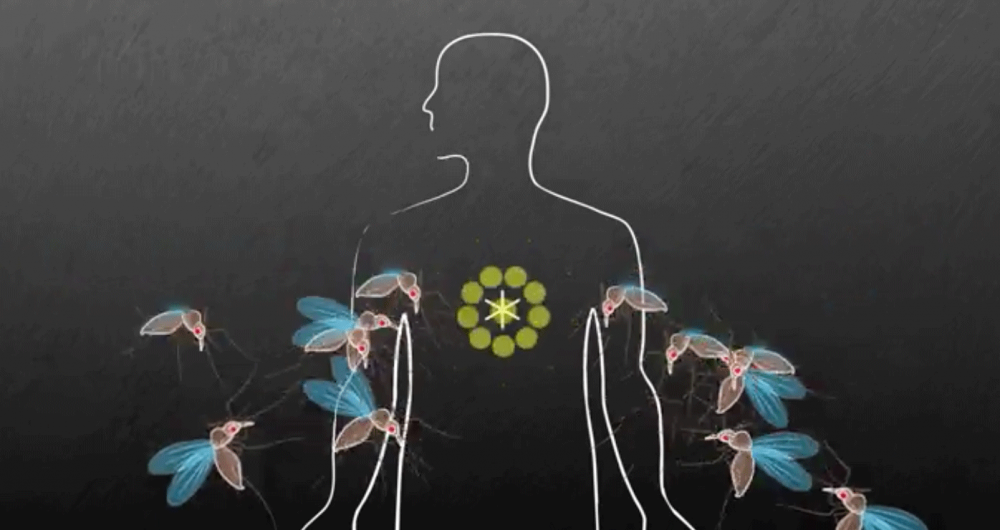

In the paper, published this month in the journal Science Translational Medicine, the researchers focused on a drug, ivermectin, which has been used to treat parasites, but also kills malaria-carrying mosquitoes when they bite a person with the drug in their system.

With funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the National Institutes of Health and a Max Planck Research Award, the team developed an ultra-long ivermectin-releasing system that could stay in the body and continuously release the drug for 14 days. Then, using simulations, they assessed the potential to eliminate the malaria parasite in real world settings. "We demonstrated that when the ultra-long ivermectin dosing system was introduced into villages and populations where malaria is highly endemic it had the capacity to significantly reduce malaria burden when used in combination with an antimalarial by shortening the life span of the mosquitos," according to a video news release this week.

Giovanni Traverso, a research associate at the Koch Institute and gastroenterologist and biomedical engineer at Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School who co-led the effort, says the new, longer-acting capsule, the size of a fish-oil supplement, can make it easier "for patients to engage with their medication." He adds: "Our new delivery systems can help address the problem of medication non-adherence which currently manifests in costs of greater than $100 billion annually in avoidable hospitalizations." He says that being able to swallow a capsule once a week or once a month, rather then daily, could "change the way we think about delivering medicines," and cites several studies that suggest lengthening dosing intervals can increase adherence rates.

Obviously, tests in pigs are not the same as tests in humans, and there are many twists and turns on the path to regulatory approval and to market for new medical devices.

I asked Dr. Bill Rodriguez, chief medical officer for the Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics, who has worked on treating and managing HIV and other infectious diseases in Africa for years, to look at the paper. His response: "In 30 years, when we're on the brink of eliminating malaria from the earth, we'll look back and say there was a moment when everything changed, when global elimination became possible. Is this that moment? I don't know. We probably won't recognize it when it happens, and they still have work to do. But it might be."

Developers of the new product cite several potential areas of concern, including possible intestinal blockage and having the drug release all at once.

Traverso says the team has addressed this through "a system composed of linkers in the star-shaped device which selectively dissolve in the small intestines mitigating this risk. As for the risk of releasing the equivalent of several weeks’ worth of drug in one go, we designed the system to hold the drug in a solid polymer."

While the current paper focuses on malaria, future plans include treatment for other illnesses, Traverso said, including neuropsychiatric, heart and renal disease, among others. He adds that eventually, the capsule might be able to release medication for one month or longer.

Rachel Zimmerman can be contacted via email at zimmerman08@gmail.com