Advertisement

Emails Offer Peek At Dealings Of Former Boston Official Who Took Bribe

His next-door neighbor had been dead for six months, and John Lynch was on the verge of buying the man's house. The price depended, in part, on what it would cost to switch the home from septic to sewer.

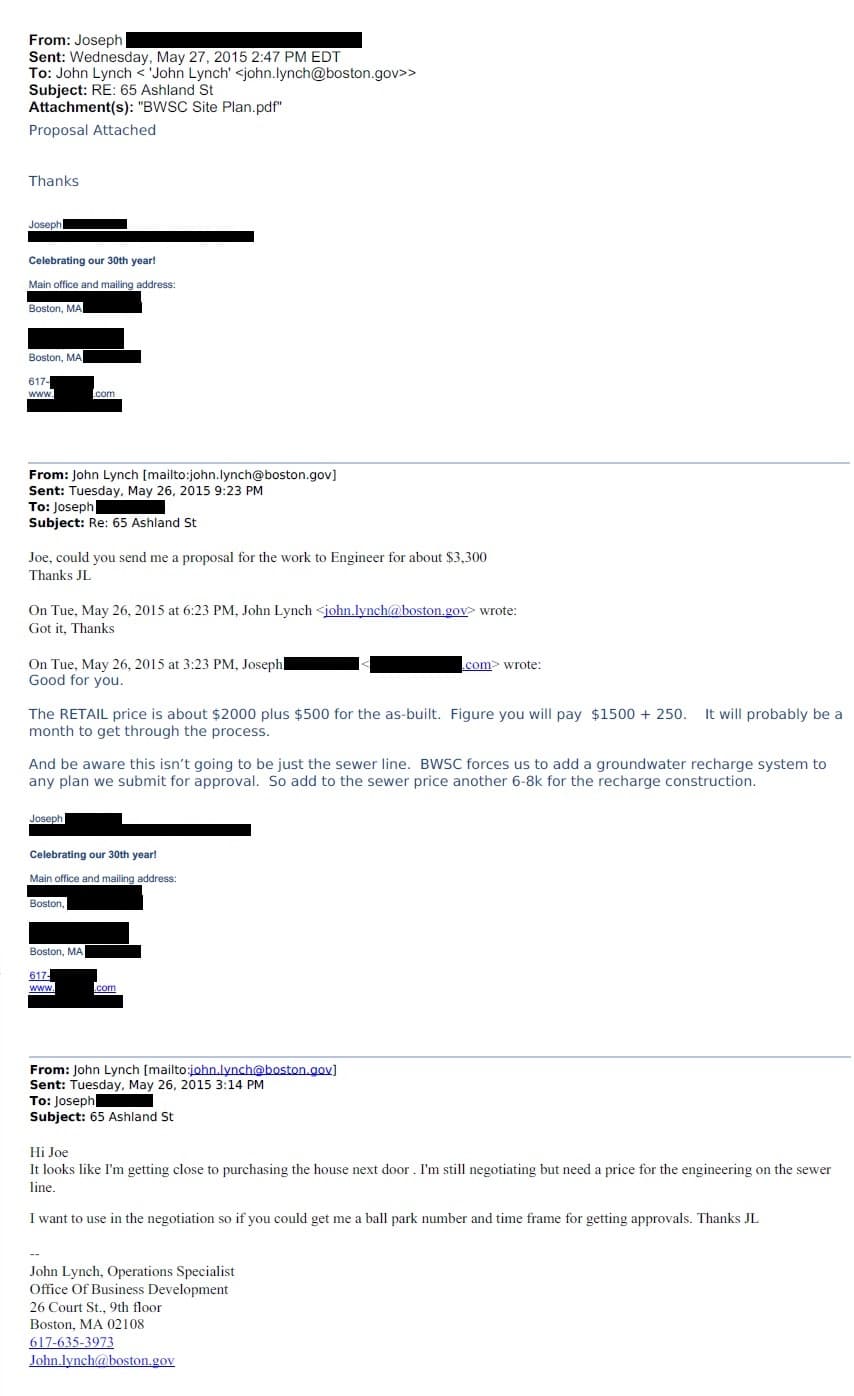

So in May 2015, Lynch, a longtime Boston official, used his city email account to ask a contractor for a quote on part of the project.

“I want to use in the negotiation,” Lynch wrote, suggesting he could leverage the anticipated expense to reduce the price of the house.

“The RETAIL price is about $2000 plus $500 for the as-built,” the contractor replied. “Figure you will pay $1500 + 250.”

The estimate for just $1,750 amounted to a 30% discount from the "retail" price.

“Got it, Thanks,” Lynch answered.

Lynch, who pleaded guilty in September to taking a $50,000 bribe on an unrelated project, may have broken state ethics laws when he used his official account to conduct personal business and apparently accepted a lower price than what is available to the general public, according to former state Inspector General Greg Sullivan.

"The state ethics laws of Massachusetts are very strict," Sullivan said. "They prohibit a public official from using public facilities, including a city email, to do private business transactions. There's a reason for it: because it's a form of intimidation. It could be a subtle form of coercion."

The contractor did not respond to questions about why he cut his usual rate and whether he felt pressured to do so. The Massachusetts Ethics Commission — which can investigate possible violations, impose fines and refer cases to prosecutors — declined to comment. Lynch's attorney, Hank Brennan, did not respond to an interview request or to emailed questions.

After Lynch thanked the contractor for offering a deal on the sewer project, he emailed again, three hours later, to ask for one more thing: “Could you send me a proposal for the work to Engineer for about $3,300[?]”

The contractor complied, supplying an inflated quote for exactly $3,300 — almost twice what he'd offered to charge.

The exchange suggests that Lynch, though grateful for the chance to save money, sought a proposal bearing a higher figure that could help persuade his deceased neighbor's brother, who was managing the estate, to lower the price of the house.

The brother, James Nolan, confirmed that Lynch presented him with the $3,300 quote, along with other cost estimates. Four years later, Nolan said, "it's odd" to read emails that suggest Lynch was engaged in "behind-the-scenes inaccuracies."

"Obviously, the man has had some difficulties in dealing with official issues. I can't ignore them," Nolan said. "But my involvement with him was always very positive."

Land records show that Lynch later obtained a construction loan from Meetinghouse Bank to renovate the property. Sullivan, who now directs research at the right-leaning Pioneer Institute, said that, in his view, if a falsified contractor's quote helped form the basis of the loan, "that would constitute bank fraud."

The office of U.S. Attorney for Massachusetts Andrew Lelling, which brought the bribery case against Lynch and also secured a guilty plea on a tax fraud charge, said it "cannot comment due to the pending case."

Lynch is scheduled to be sentenced in January.

Lynch's exchange with the contractor is one among thousands of email chains that the city of Boston has released, as Lynch awaits sentencing in the corruption case. He has resigned as assistant director of real estate in a division of the Boston Planning and Development Agency. Lynch had worked for the city since 1977, spending the bulk of his career in the Department of Neighborhood Development.

Many emails show Lynch to be an affable networker who used the relationships and knowledge he cultivated over four decades in city government to help constituents solve problems. Some other messages add to evidence that he sometimes used his position for personal gain.

WBUR previously reported that Lynch may have improperly accepted a discount when he paid just $200,000 to buy the house beside his own from his late neighbor's estate. The neighbor had several years earlier received a $25,000 interest-free loan for roof repairs and new windows from Lynch’s city agency. Emails do not indicate whether Lynch played a direct role in the loan.

The emails do reveal a licensed appraiser said the house, in Dorchester's Clam Point neighborhood, would be worth $270,000 once connected to the public sewer system. The appraisal was conducted to determine fair market value prior to the 2015 sale.

Nolan, who sold the house to Lynch as executor of his brother's estate, said he agreed to lower the price partly because of construction costs and because he could avoid paying a broker's fee in a private sale to Lynch. But those were not the only reasons.

Emails show that Lynch repeatedly used his official email account to perform favors for his neighbor while the man was alive, helping him navigate the state's Mass Save energy program, complete insurance paperwork, and even find someone to take a seldom-used bicycle off his hands. Nolan said Lynch's wife also was very helpful.

Reducing the price was a way of showing appreciation for years of assistance, "to a certain extent," Nolan said.

"If he was going to get a good deal out of it, he and his wife certainly treated me and my brother very well," Nolan said.

Neighborly kindness is hardly a crime, but Sullivan said Lynch may have violated the state's conflict-of-interest law if he used his official position to assist the man next door and, in return, accepted a real estate bargain.

After buying the property, Lynch successfully petitioned Boston’s Zoning Board of Appeal to waive a restriction on two-family homes so he could raze the house and build a duplex. He ultimately sold the duplex’s two units for almost $1.5 million, combined — more than seven times what he paid for the property.

Possible Connections To The Bribery Case

Additional emails shed light on Lynch's relationship with Craig Galvin, the former zoning board member who resigned shortly after Lynch admitted to taking a bribe. Galvin has not been charged with any crime.

In the years before Lynch accepted a developer's $50,000 payoff, on the premise that he could sway the vote of a zoning board member, he helped Galvin's real estate firm collect broker's fees on at least three properties.

Most recently, Lynch retained Galvin's firm to sell at least one of the duplex units he built in Clam Point. The broker's fee does not appear in emails reviewed by WBUR, but a conservative estimate is $14,700, which represents 2% of one unit's sale price earlier this year.

A purchase and sale agreement included in the emails shows that in 2014 Lynch hired Galvin's firm to broker the sale of two properties owned by an elderly woman who had named Lynch her trustee. The fee was $11,750.

WBUR previously reported that in the late 1980s, the woman used a low-income housing program administered by the Department of Neighborhood Development to purchase a house and adjacent lot in Dorchester, and received loans from the same agency totaling $28,523. At the time, Lynch was a residential development manager in the agency, but it is unclear whether he was directly involved in the purchase and loans.

Public records show that years later, near the end of the woman's life, she transferred her properties into a trust and named Lynch the sole trustee. At the same time, she signed a will that put Lynch in charge of her entire estate. The transactions did not mean that Lynch would inherit the woman's money or properties, but they may have entitled him to management fees.