Advertisement

PhotoShocked: How Google Image Randomly Creates Our Online Legacies

This week, an editor in need of my photo breezily told me, “No need to send one — I’ll just find something online.”

Curious to see what she’d retrieve, I went to Google images and typed in my own name.

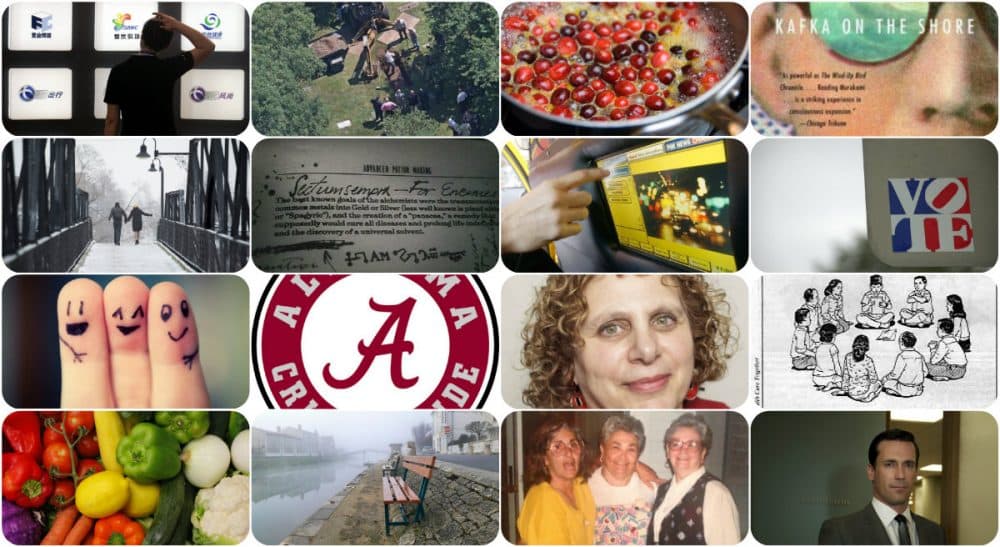

The first six images on the page were headshots from my corporate website, a timeline of my increasingly middle-aged hair styles and colors from the past decade. The hundreds that followed made up a bizarre assemblage of conference logos and pictures, book covers, people who possibly knew other people I might have met — a motley collection including:

- A Boston Globe photograph from July 2013 showing an aerial view of workmen exhuming the grave of Albert DeSalvo, the Boston Strangler;

- Covers of Haruki Murakami’s “Kafka on the Shore” — a book I’d reviewed in 2005 -- in eight different languages;

- A picture of a Hispanic woman in a gray Nike sweatshirt and handcuffs;

- A single photograph of my husband, uncharacteristically bound in a buttoned up white shirt and tie;

- A stunning photo of Jon Hamm playing Don Draper, and less handsome images of Hillary Clinton cleaning her glasses and Barack Obama in khaki shorts, driving a golf cart;

- The logo of the Alabama Crimson Tide;

- An empty road running alongside a foggy river;

- A newspaper drawing of Indian and Asian teens sitting cross-legged in a circle, accompanied by the caption: “Talking together is an effective way to develop good communication skills;”

- An annotated paragraph from a book chapter titled “Advanced Potion Making;”

- A grainy family photo of three women, their arms slung around each other’s shoulders, associated with an article titled “Three Sisters: Joined at the Funny Bone;”

- Army photos, family reunion photos and obituary photos of a man I’ve never met.

I’ve been ruminating about this last set of images, copious and more personal than the others. The Army private looks dapper and crisp, though in the black-and-white portrait taken what looks like a decade or two later, he’s a bit doughier and less somber. The family reunion shots in faded color show a genial man surrounded by children and grandchildren, sunburned and dressed for Florida. They look just like the hundreds of photos of my family, taken over years of ski trips, birthday parties and eventually winter vacations in Sarasota.

But they’re not my family. The man in the photos was the father of a professional acquaintance named Pete, an ad agency executive who was an early champion of blogging and Facebook and Linked In. I’d met Pete at a couple of conferences, friended him when that was a new verb, and offered some perfunctory condolences when he posted news of his father’s passing. His prominence in social media since its inception has swept his family photos onto my Google image page, blowing those scallop-edged images of his dad posing for the camera (when it was a camera and not a phone) far and wide, like pollen in the wind.

If it’s only my public life that’s durable, shouldn’t I be posting more often, with care to crafting my online legacy rather than leaving it to Google’s associative prowess?

Though it’s not Pete’s fault, I’m resentful. If Google is going to serve up a faded photo from the 1940s of a young man in an army uniform, I want it to be my father. If I’m going to see an elderly man reveling in the glow of his sun-painted grandchildren, I want those buttery little girls to be my daughters. But my father is absent from these pages and pages of images, as are my mother, brother, my daughters and granddaughters.

I should be glad that my online privacy settings are holding fast. Instead, these grainy, predictable and precious photos of other people’s families arrayed on page after page make me feel misrepresented and strangely robbed of my own past. If my name is going to be associated with pictures, shouldn’t they be pictures of my own choosing, my own people? If it’s only my public life that’s durable, shouldn’t I be posting more often, with care to crafting my online legacy rather than leaving it to Google’s associative prowess?

But then I hear my daughter’s gently mocking reproof in my head, telling me to “simmer down.” My life did, after all, begin long before the social web, and its dearest moments are rendered much more vividly in my mind than they could be in any visible image. Photos will never tell the story of how this life has felt. And, I suddenly realize, despite the cheap longevity promised by online storage in the cloud, they’ll never make it eternal.