Advertisement

It’s Time For Boston To Honor Its First Irish Superstar

Only a sports-mad city like Boston could field such a dream team of bronzed athletic gods. From Bobby Orr to Ted Williams, Doug Flutie to Harry Agganis, a Hall of Fame roster of Boston sporting legends has been honored with statues, and this past fall, Celtics great Bill Russell and Red Sox slugger Carl Yastrzemski became the latest icons to have their likenesses forever frozen in time. It’s an impressive constellation of superstars, yet there is one glaring omission at the top of this lineup — Boston’s first sports hero, John L. Sullivan.

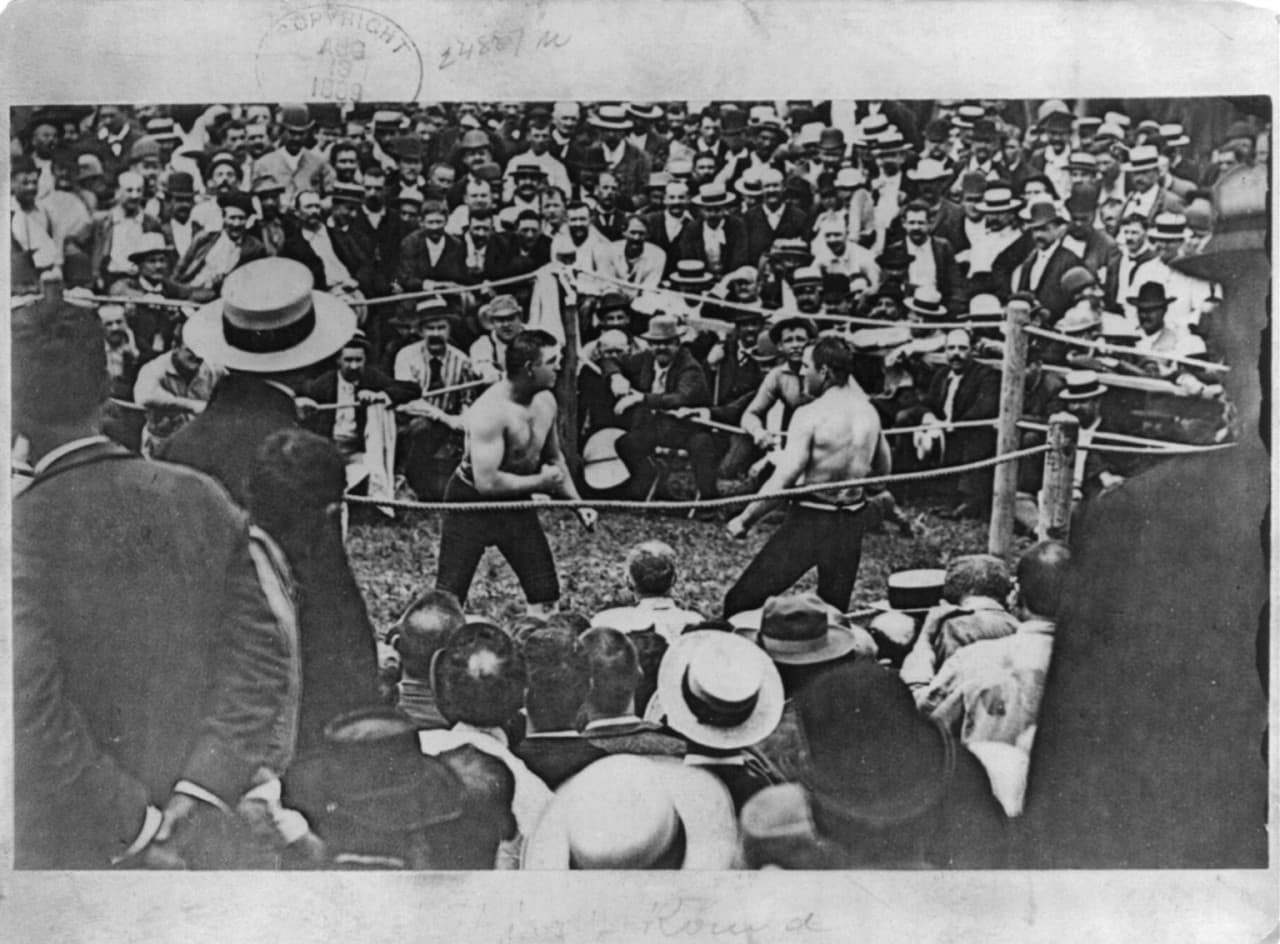

If sports are Boston’s secular faith, Sullivan is not only among our pantheon of athletic gods, he is our Zeus. Born and raised in the South End, the larger-than-life Gilded Age boxer who reigned as heavyweight champion for more than a decade was the first athlete to earn a million dollars, the country’s first sports superstar, and one of the first Irish-American idols. Sullivan transformed boxing from outlawed bare-knuckle fighting into the gloved spectacle we know today. His oversized personality and epic brawls, such as his 75-rounder against Somerville’s Jake Kilrain in 1889 (photo below), captured the public’s imagination at the dawn of American mass media. Displaying his showman’s flair, Sullivan literally challenged all of America to a fight, barnstorming the country and offering $1,000 to any man who could simply last 12 minutes in the ring with him. The champ never paid out a dime.

Everywhere he traveled — from England to Australia — the “Boston Strong Boy” carried the Hub’s banner. Sullivan’s fame burned so brightly that legions of fans paid just to watch him pitch in exhibition baseball games, mimic the poses of ancient Greek statues, and headline theatrical productions such as "Uncle Tom’s Cabin." Women purchased Sullivan’s shorn hair from his Dover Street barber to snap into their lockets. “Let me shake the hand that shook the hand of Sullivan” quickly became a cultural catchphrase, and wherever John L. traveled, an outstretched arm always reached in his direction.

If sports are Boston’s secular faith, Sullivan is not only among our pantheon of athletic gods, he is our Zeus.

When Sullivan captured the heavyweight title in 1882, no one celebrated harder than the Boston Irish who had felt emasculated in the wake of the Great Hunger, powerless under the thumb of the British in their homeland, and blistered by Brahmin scorn since their arrival in the city. Sullivan’s strength and self-confidence were potent elixirs for a people who had suffered a generation of malignant shame. John L. was so beloved in the Hub that its citizens raised $10,000 to purchase a glorious 16-karat-gold championship belt studded with 400 diamonds that it bestowed upon him before a packed house in the old Boston Theatre.

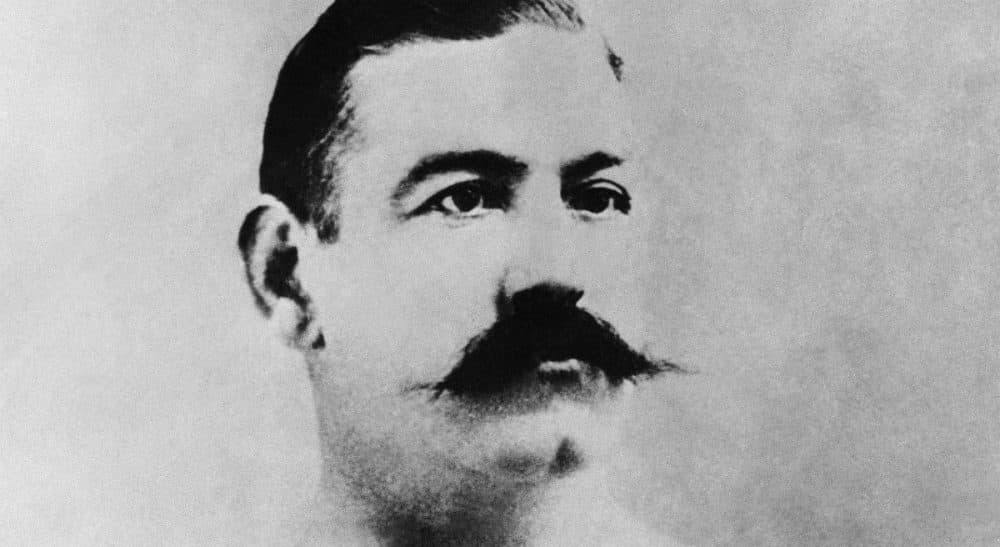

Although his image only lives on in black-and-white photographs, Sullivan was hardly some sepia-toned relic from a bygone era. Like many modern-day athletes whose celebrity transcend sports, Sullivan endorsed products, penned his own memoirs, flirted with political office, and owned his own sports bar.

Tributes to Sullivan are sprinkled across the country, and a life-size statue of the mustachioed brawler with his bare fists at the ready has just been erected in Abbeydorney, Ireland (photo to the right), the small village in County Kerry from which Sullivan’s father emigrated in the wake of the potato famine. Yet, there is not so much as an historical marker to the “Boston Strong Boy” in his hometown. Sullivan blazed the trail for Orr, Yaz, Williams and every other Boston athlete cast in bronze, and it’s time that he received a similar honor.

A recently unveiled statue of 1950s welterweight champion Tony Demarco at the corner of Hanover and Cross streets now greets visitors to the North End. It would only be fitting to place a bookend tribute to Sullivan, another ethnic hero, on the opposite side of the city at the gateway to his old South End neighborhood.

Like many public figures, Sullivan led a life pocketed with deep valleys that mirrored its high peaks. He was an indifferent husband and father plagued by the insidious alcoholism and racism so prevalent among the Boston Irish in the Gilded Age. Still, a statue is not a canonization, and Boston has erected monuments to its fair share of rascals, such as Sullivan’s close friend James Michael Curley.

We have been reminded in the past year about the toughness and resilience of the people of Boston, a scrappiness that was made flesh in Sullivan. As we celebrate the Celtic contributions to the city this St. Patrick’s Day, it’s time to remember the native son who embodied the legendary spirit of the fighting Irish. It’s time for Boston to honor its “Strong Boy.”

Related:

- Radio Boston: The Legacy Of Boston’s ‘Strong Boy’

- Thomas J. Whalen: The ‘Eagle’ Is Landing — Bill Russell Statue Is Coming… Finally